London’s Blenheim Forge uses ancient techniques and instant-coffee baths to produce its exceptional steel blades

Blenheim Forge began in the most modest way imaginable: with a homemade brick oven in a garden, powered by a leaf blower. A decade later, founders James Ross-Harris, Jon Warshawsky, and Richard Warner create coveted blades that rise to the level of collectible and count celebrity chefs Gordon Ramsay and Francis Mallmann, among others, as clients.

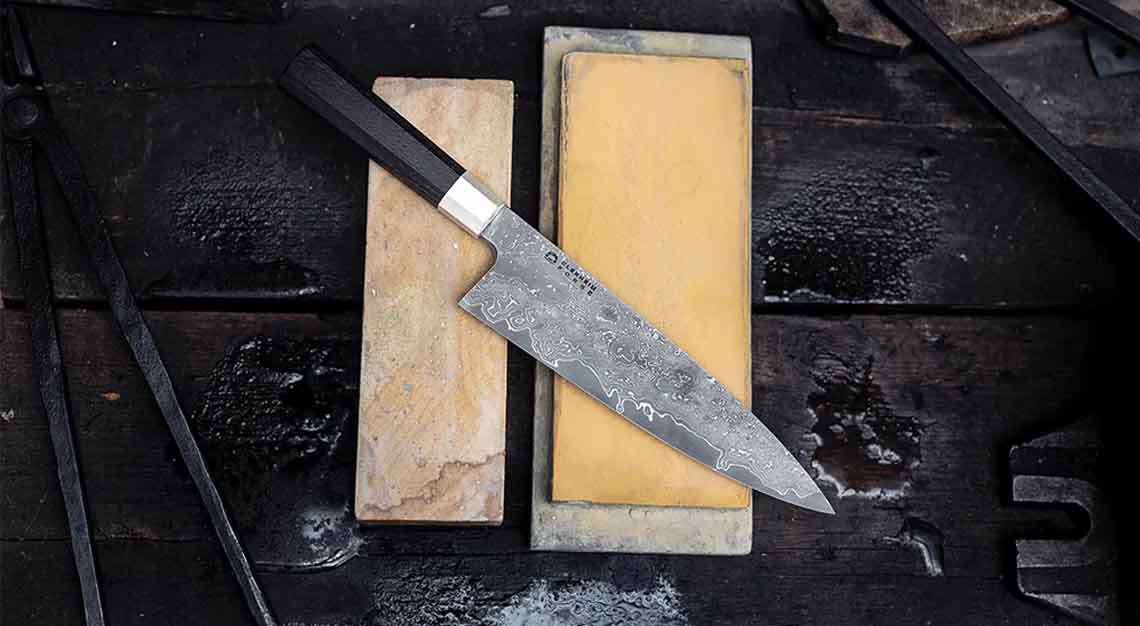

As beautiful as they are functional, Blenheim knives are painstakingly handmade in London in a process that combines modern metallurgy with centuries-old Japanese sword-making techniques. The bladesmiths push steel to its limit—and sometimes beyond: Many blades must be scrapped, but those that survive are extremely strong.

Today most knives are made from recycled steel; even prominent luxury brands turn out blades that might have started life as a Honda Civic. Recycled steel is cheaper, but while quality knives can be fashioned from it, impurities weaken the metal slightly. Chasing perfection, Blenheim Forge instead uses its own proprietary virgin steel. To meet the minimum order requirements of a multinational German manufacturer, Blenheim had to purchase enough steel to last it 25 years. “It’s a 3.5 percent tungsten and 1.4 percent carbon alloy,” says Ross-Harris.

“It’s not a million miles away from Aogami Super-steel or Blue Paper Steel,” two of the most respected Japanese types, “but ours is even purer.”

And in the Blenheim team’s view, there’s no point in starting with such a fine raw material if you’re not going to be as fastidious about every facet of production. “If you skimp on any other step, this pinnacle steel becomes worthless,” Ross-Harris explains.

The virgin core steel is sandwiched between two 60-layer claddings for support. The resulting Damascus steel is renowned for its aesthetic, the mottling reminiscent of flowing water. Here’s how a special-edition 210-millimetre chef’s knife (part of a limited-edition set available exclusively to Robb Report readers and which, were the knife available individually, would be priced at more than US$1,700) is made.

1. In the raw

In preparation for forging, Ross-Harris (pictured) alternates layers of six-millimetre steel and one-millimetre nickel, then welds them together to create two billets, each roughly 16 centimetres (about six inches) thick. When finished, these will form the cladding on either side of the core steel.

2. Hammer it out

The metal billet is heated until it softens slightly; the forging process then bonds the layers of steel and nickel together. The bladesmith strikes the 16-centimetre billet with a 100-year-old power hammer until it’s only a single centimetre thick. You can call this stage solid-state-diffusion bonding or forging, says Ross-Harris, or “hitting really hot metal with a really big hammer—the more you hit it, the harder it gets.”

3. Feeling the heat

The one-centimetre core steel is now sandwiched between the two one-centimetre claddings and heated to a high temperature, which is gauged by eye. It’s a critical part of the process: Too low a temperature and the metal will crack when struck; too high, the steel layers expand into one another, and it will be impossible to achieve a fine edge. “It’s an easy place to ruin a knife,” warns Ross-Harris. The metal is now rolled into its final 0.7-centimetre thickness and hammered into shape, including setting the tapers and the bevels. The profile of each blade is then refined on grinders and belts.

4. Running hot and cold

Heat treating is the process of heating (to temperatures around 821 degrees Celsius) and cooling the metal multiple times, which alters its atomic structure. The aim is to create as rugged and fine-grained a blade as possible, and the technique takes several days. The final step is a rapid submergence in hot oil. Two out of every 10 blades suffer “irreparable delamination, cracking, and warping,” according to Ross-Harris. The steel is now at its hardest but is also brittle like glass, so the surviving blades are tempered in lab ovens, where some hardness is sacrificed for increased durability.

5. It’s a grind

At this point, the 121-layer blade scores around 64 on the Rockwell hardness scale, which is at the high end for knives and chisels. Progressively finer grinders and wheels are used to bring the blade to its end shape and profile.

6. Bath time

Etching the blade in two solutions brings out the aesthetic beauty of the Damascus steel. First, it’s dipped into nitric acid for 20 seconds, which gently eats away tiny amounts of the medium carbon steel. Then, to highlight the shine of the nickel and darken the steel, the blade spends four hours in a bath of instant coffee. “There’s an unknown combination of acids in it that works particularly well,” explains Ross-Harris, “and we haven’t been able to find a better substitute.”

7. Fossil energy

For special editions, Blenheim uses solid-silver ferrules, or rings, and wood from the 5,000-year-old fossilised Fenland Black Oak unearthed about a decade ago in East Anglia, England. The slow crystallisation of the tannins has turned the now incredibly hard oak jet-black. After being bonded to the blade, the handle cures for another day.

8. Show a little grit

One Blenheim artisan, Menelik Ekani, specialises in sharpening and honing the knives and polishing the final edge. In this time-consuming endeavour, progressively finer and finer grits create bevels, then micro-bevels. These knives will be paired with the rest of the set in a unique leather portfolio handcrafted by Harry Owen, a London artisan.

This chef’s knife is part of an exclusive limited-edition set created as a collaboration between Blenheim Forge and Robb Report that also includes a paring knife and a carving knife and fork. Twenty-five sets are available, priced at US$5,750 each. Robb Report will make a commission on any purchase. For enquiries: [email protected]

This story was first published on Robb Report USA