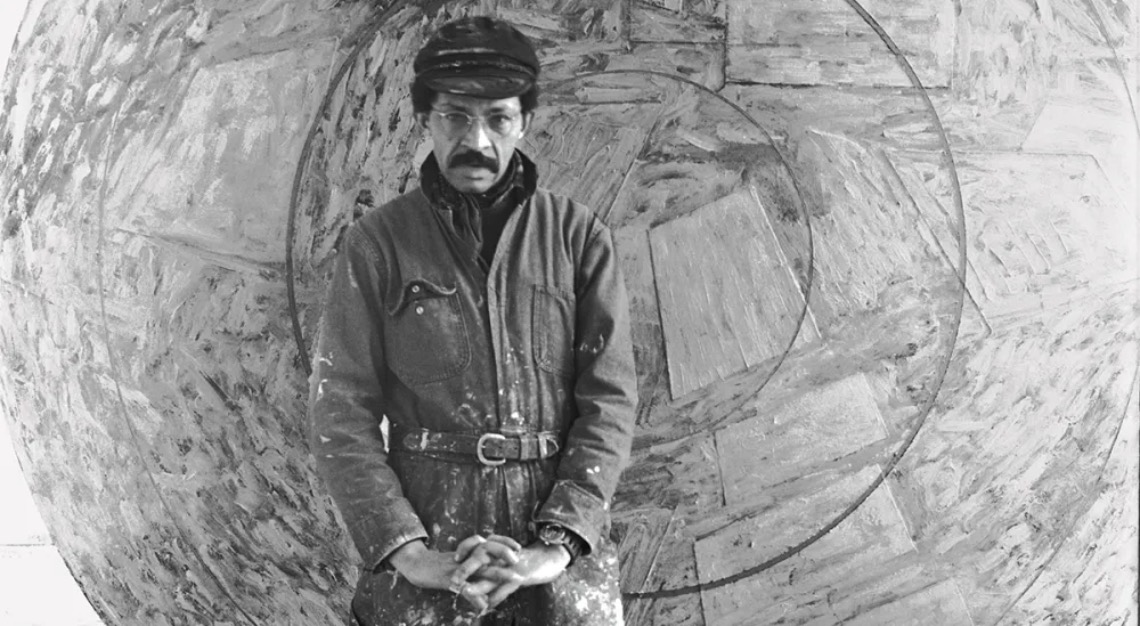

The career-spanning exhibition will feature 175 works from Whitten’s dynamic, rule-breaking oeuvre

“When my paintings cease to be challenging, I will simply find something else to do,” Jack Whitten wrote in a 1988 letter to the artist and eminent scholar of African American art David Driskell. Whitten, who died in 2018 at the age of 78, never did need to find another way to fill his time.

Respected for his hungry mind and his ceaseless experimentation—but perhaps never fully given his due—Whitten is the subject of his first comprehensive retrospective, opening March 23 at the Museum of Modern Art. It’s an appropriate host: The first museum he visited in New York City, MoMA began acquiring his work in the 1970s. “He fits so perfectly into the mission of trying to better understand modern- and contemporary-art figures who have been watershed and yet may not have gotten the recognition that they’ve deserved thus far,” says Michelle Kuo, MoMA’s chief curator at large and publisher, who met Whitten in 2011 and organised the exhibition.

The show’s more than 175 works will span nearly six decades of his practice, which explored the Civil Rights Movement, science, and technology via an impressive range of disciplines including painting, sculpture, collage, photography, printmaking, and music. A tenor saxophonist, he brought an improvisational approach to his work.

Born in 1939 in Jim Crow Alabama—he labeled the all-encompassing segregation “American apartheid”—Whitten learned to paint with the materials left behind by his mother’s first husband, a sign painter who had his own business, a rarity for a Black man in that milieu. Whitten’s first paid commission was a civil-rights poster.

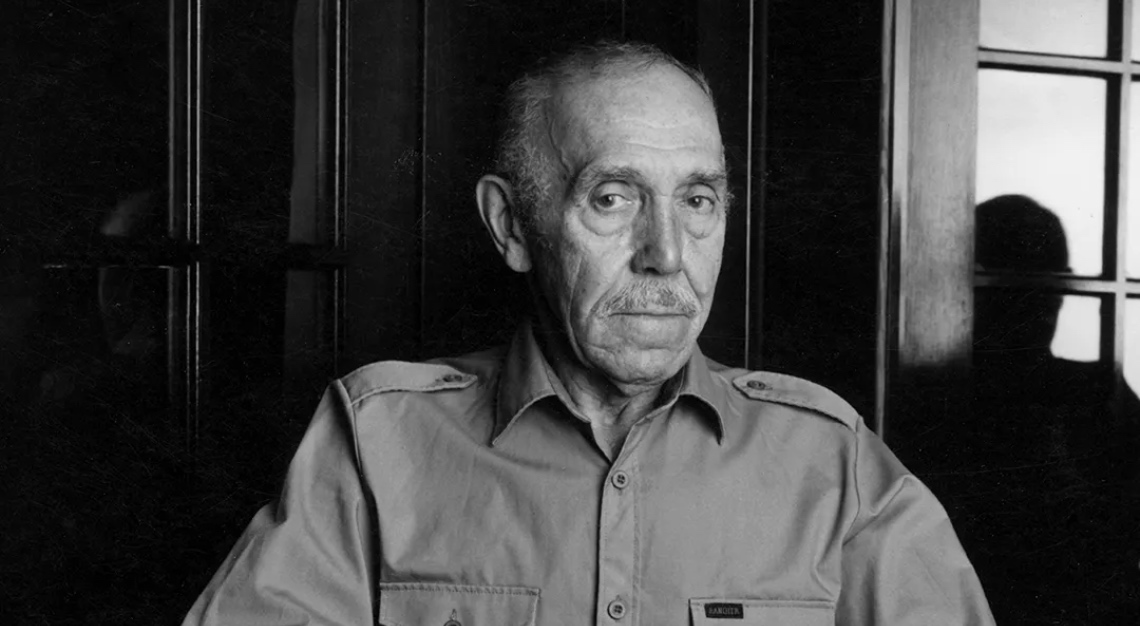

He entered college on the pre-med track but then changed course and began to study art. Eventually, he made his way to New York, where he was the only Black student in his class at the Cooper Union. He arrived in 1960, when the art world was still small enough that a newbie could drink at its undisputed canteen, the Cedar Tavern, with his Abstract Expressionist idols—Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline—and find mentorship from a trio of Black artists who’d made their mark: Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Norman Lewis. Whitten lived on the Lower East Side, where he marveled at the racial integration. He also immersed himself in jazz circles, meeting John Coltrane and Art Blakey, whom he likened to a witch doctor on drums.

At a time when many Black artists felt pressure to use a representational style to advance social activism, Whitten embraced abstraction as a potent lens on the world’s ills, pushing the genre forward with inventive techniques that he carefully tracked in his studio log. In the early 1970s, he developed one of his best-known techniques: He poured layers of paint into “slabs” on the ground, then used rakes, squeegees, Afro picks, and other tools to dig grooves, creating apertures into what lay beneath the surface. He also did a residency at Xerox, a catalyst in his experiments with chemicals used in photocopying.

Around 1990, Whitten hit upon his signature mosaic method, building thin layers of acrylic paint, then cutting the dried surface into “tiles,” which he then re-formed intuitively into mesmerizing shapes and swirls. “It almost looks like he just had a field of tiles and then splattered them,” Kuo says. “But if you look closely, you see that each tile is not continuous with the other. It’s this recombined, incredibly intricate, multi-dimensional puzzle.”

Whitten long spent his summers with his family in Greece—he would sign out of his New York studio log with the simple “Gone fishing.” On the island of Crete, he’d connect with ancient Cycladic art and Byzantine mosaics and make sculpture using local materials.

The retrospective’s subtitle, The Messenger, nods to both one of his works—a canvas ode to Art Blakey—and his mission. Says Kuo: “I see him as someone who channeled or even transformed experiences with grave injustice throughout his life into a kind of visionary beauty. He often said, ‘I am a conduit.’ ”

This story was first published on Robb Report USA