Snap Chat

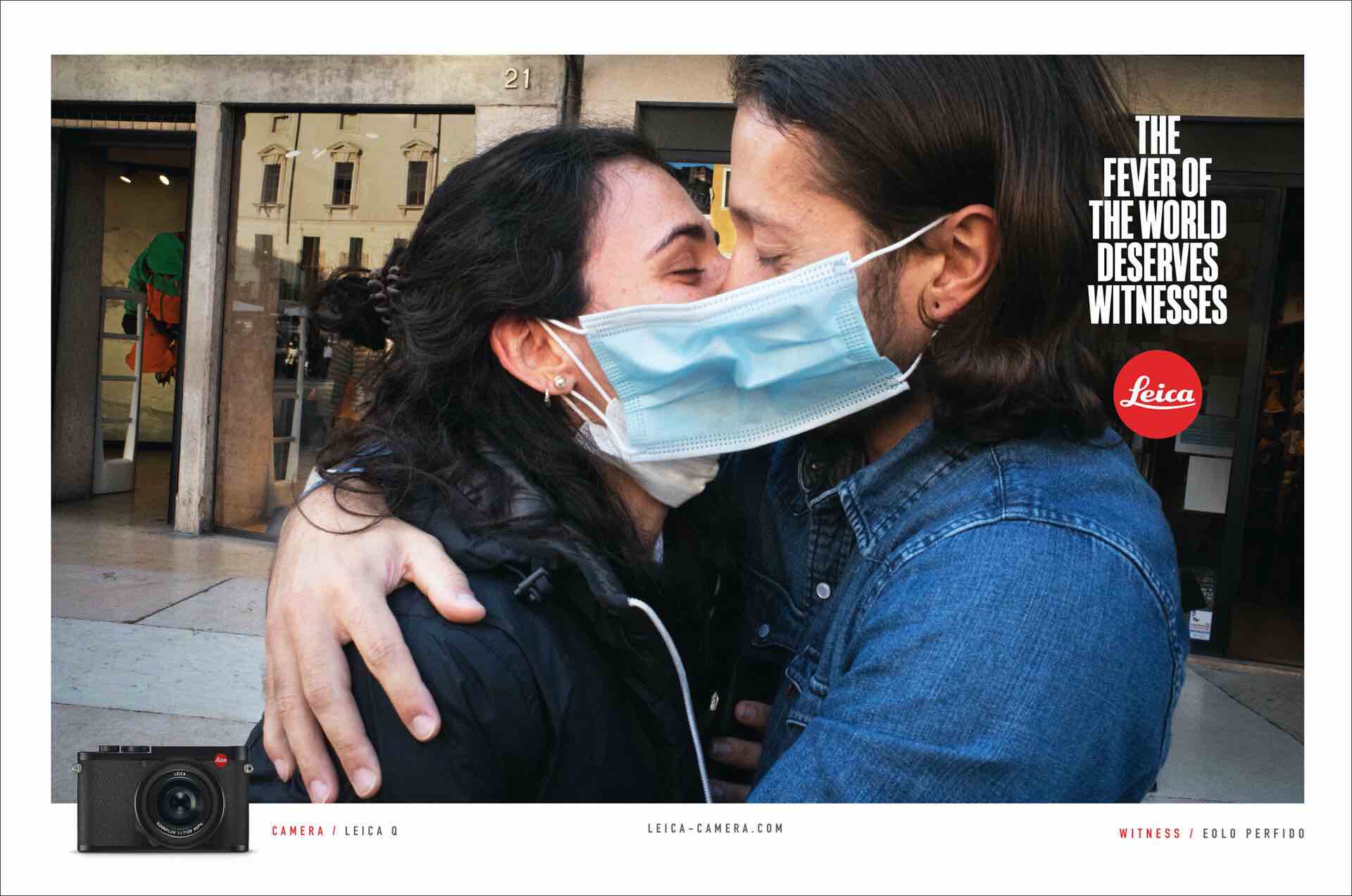

Believe it or not, Ion Orchard turns eight years old this year. Well, we almost didn’t believe it either – a testament to how relevant it still is to the local shopping scene. At any rate, to celebrate its eighth year, Ion Art Gallery and Leica Camera Asia Pacific are hosting a photography exhibition.

Titled Celebration of Photography, the exhibition brings together a diverse group of nine local and international photographers who use Leica cameras. There, the artists will show off an equally diverse body of work, ranging from showcasing cultures in far-flung reaches of the world, portraits and even the abstract.

What is common to all those images is how evocative they are, and the deeply talented individuals behind the cameras. We caught up with all of them on the opening day and asked them what made them, and their art tick.

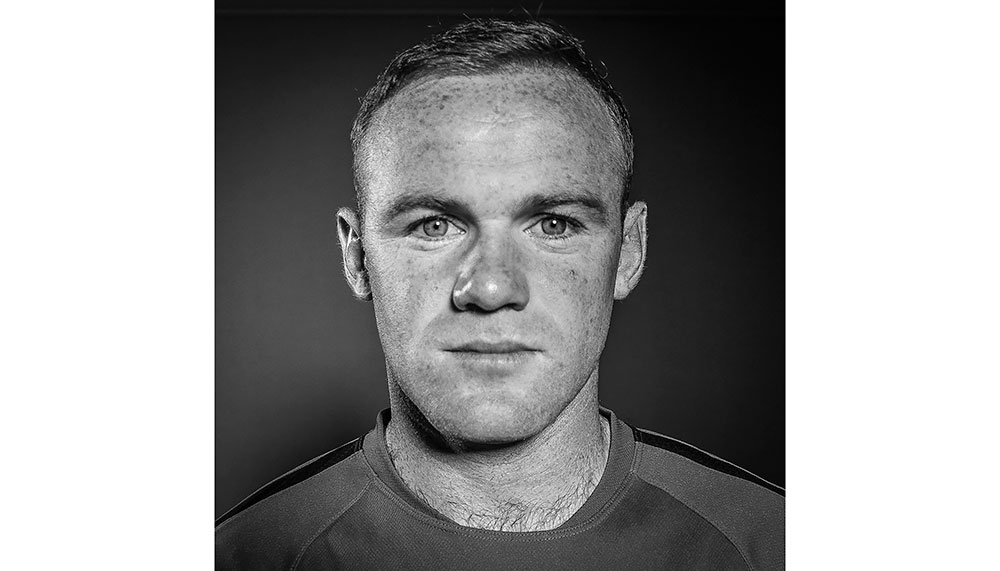

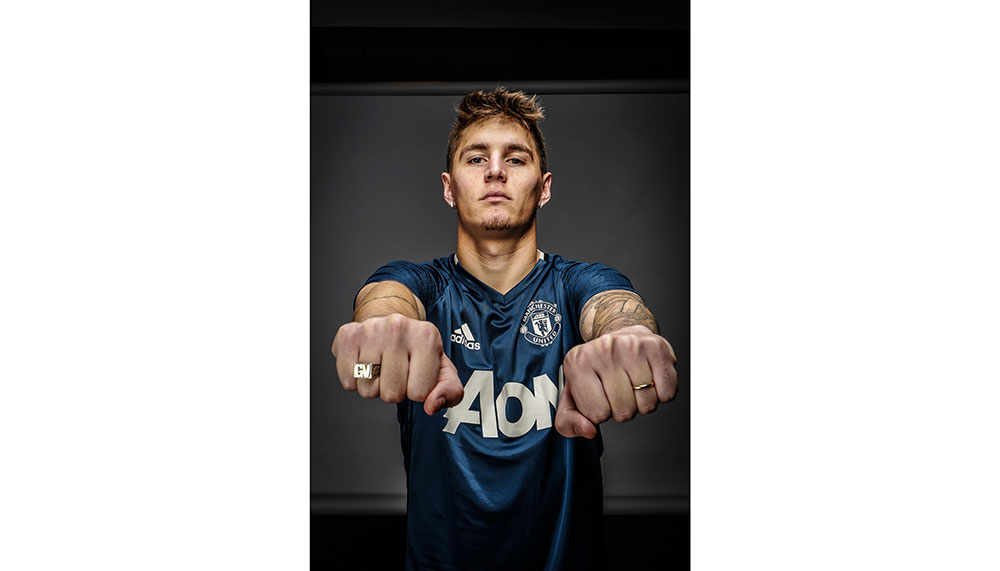

Eric Sawitoski

Sawitoski’s intimate portraits of players from the Manchester United Football Club shows some of sport’s greatest stars as they really are.

You shot footballers from Manchester United, who are obviously not professional models. Was that difficult?

Photography is about making a human connection. Anyone can be difficult to shoot if you don’t have that. Language was also a barrier. Some didn’t speak English, so making that connection was tricky.

You said you didn’t grow up with football, so was shooting and creating a connection with a with athletes whose sport you don’t play easier or more challenging?

I think it was refreshing for them. One of the things I bonded with them over was their children and family life. I can talk about what it’s like to have a two-year-old and how I’d like to be in bed by 9pm. A lot of people think footballers are celebrities, but they’re also family men. Another thing we talked about was gaming, because a lot of time they’re travelling on long flights, and they play video games.

Laxmi Kaul

For this series, Kaul ventured to northern India to photograph scenes of the Holi festival for in a joyous celebration of uniquely Indian culture.

You don’t have any professional training in photography. Do you think this has helped or hampered your art?

I’m so glad I didn’t go to any school for this. My first teacher was my father, and I started when I was eight years old, but he passed away when I was 11. Nobody ever took his place. Maybe I didn’t allow it, or want it, or maybe it was just not meant to be. But I’m glad I’m self-taught because I learnt to fall and get up on my own, and that’s how I learn as well. I’m also not looking at it through someone else’s eyes.

For this series and your last one, it’s a celebration of Indian culture. What is it that attracts you to tell those stories?

I like to show cultures in their natural surroundings. The last series I shot was living on the border of India and Pakistan. There was no cultural event, it was just bullets being fired on both sides. That’s a part of the country that even people living just 100km away don’t see, because they’re afraid to go there. I saw how they lived and saw how they survive. In this series, I wanted to take that happiness and bring it forward. India is the cultural hub of everything – spiritualism, culture, it’s a part of all of us. I wanted to show that. And there were foreigners at the festival too. They were having the time of their lives there.

Francisco Marin

As an architect by training, Marin used his professional eye to capture some stunning architectural forms.

In this series, there’s a noticeable lack of people. Do you find it harder to shoot people than objects?

I’m not a people photographer. Not because I’m shy, but I don’t like to invade people’s spaces without reason. I lived for nine and a half years in China, and all I see there are tourists getting in the way of people, like construction workers or people carrying heavy rattan baskets. Foreigners, out of curiosity, will try to capture those images to show their friends. “Look at what I found in this faraway land.” I come from Mexico, another developing country. So what I saw in China, I see all the time. It’s not surprising to me, so I walked away from that.

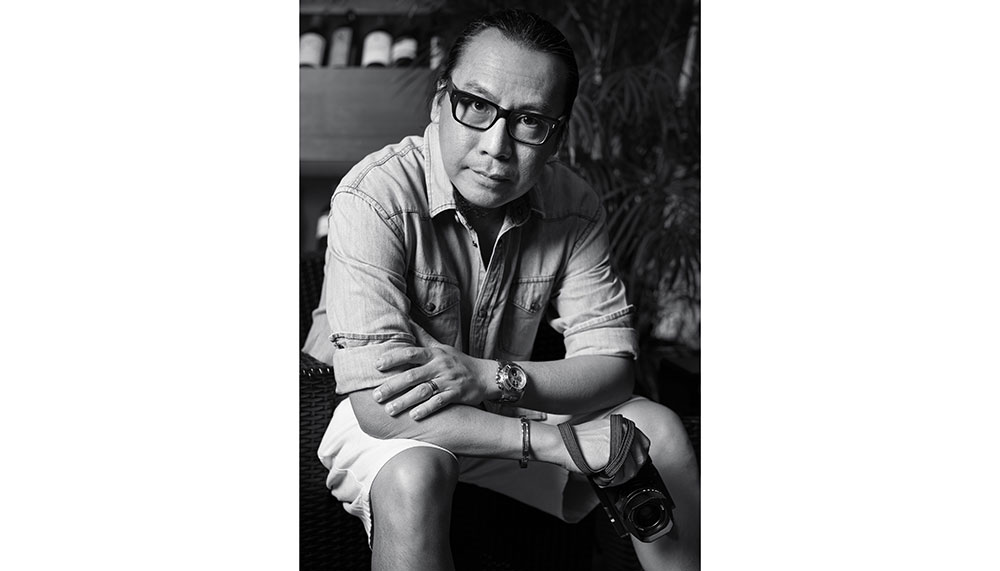

Andrew Lum

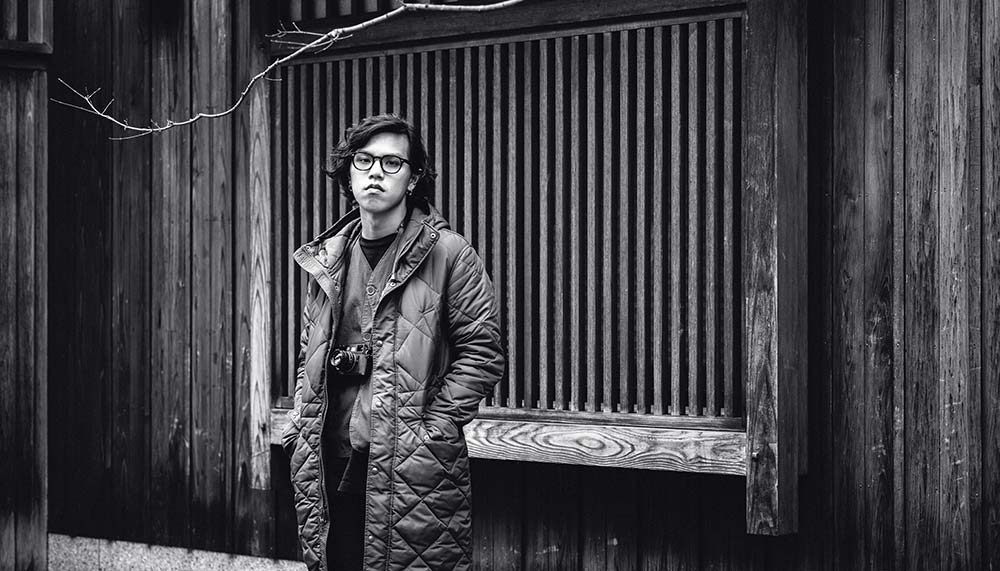

The multi-talented Lum’s series Distilled focuses on people and emotions in their purest, most candid form.

You’ve dabbled in music, photography and now, mixology. Where to next for you?

I’m not sure myself, but what I noticed is there’s a common denominator linking them all. They all trigger some kind of sensory reaction. With music, it’s about quiet and loud; food is about balancing the five flavours; photography has colours, light and shadow. What interests me with photography is capturing something I see and it comes through in the images I capture.

You say you carry your Leica wherever you go, were there any moments you wish you caught, but couldn’t?

I can’t name any specific moments, but yes, there have been times like that. I feel really frustrated when I miss a moment. It’s not because I don’t have a camera with me, because with smartphones you can take pictures anytime. Mostly, it’s because I wasn’t quick enough, or I took a picture at the wrong time. One of the things I learned in photography is even when you think you captured the perfect moment, you might not. Something might come along just after that that’s more intense and might tell a better story. I’ve learned not to let it get it down and just to keep at it.

KC Eng

For Jalan Jalan, Eng plays with light, colour and form to present some very familiar objects in very unfamiliar ways.

Your work in this series is very abstract. What sort of feelings were you trying to evoke with them?

I’m just showing what was presented to me in a different way. I don’t manipulate the subject in any way. The photos in this series is more about colours and lines. I want my work to be soothing and that a normal piece of canvas can be totally beautiful. It’s like bubbles flying through the air, when it hits the ground, it’s over. That’s what I’m trying to capture.

A lot of the photos you’re exhibiting in Jalan Jalan are very close-up shots, without much context. Was that deliberate?

It’s not that close-up, actually. It was taken from pretty far away. I used light and shadow in my photos to give the illusion of space. It also captures the essence of the structures as light falls on it. With the photo I took of the Inari shrine, you see the pillars, but you don’t see the entire shrine. It’s a different perspective of the same thing. I’d rather show something abstract, and not what a personally normally sees. It’s about picking out just the essential parts of an object.

Yuey Tan & Claire Jedrek

Husband and wife racing drivers Tan and Jedrek turn their passion for motorsport and photography into intimate track-side portraits.

Both of you started fairly late with photography, how did your journey begin?

Jedrek: Before I got into photography, I realised I never really had a love for anything in my life. I’ve never been into movie stars as a teenager, I was never obsessed about anything until I got into motorsport about five years ago. I then pick up a Leica and I never really looked back.

Are there any photographs in your collection that particularly stuck out?

Tan: One of them was in Tokyo. We go to the Fuji Speedway every year to race, and before that we spend a few days in Tokyo. There’s this one photo of Claire where she turned around as a train was coming past. There are all these still images through the train windows, but the train was a big blur and she was really sharp. I really enjoyed that one.

Jedrek: I enjoy shooting at the track. There’s just so much that goes on every weekend. But this one photo of Francis Tjia, who has been racing for over a decade and it was just of him talking. There’s something about that, him looking out on the racetrack and chatting. It’s very intimate.

Marc Tan

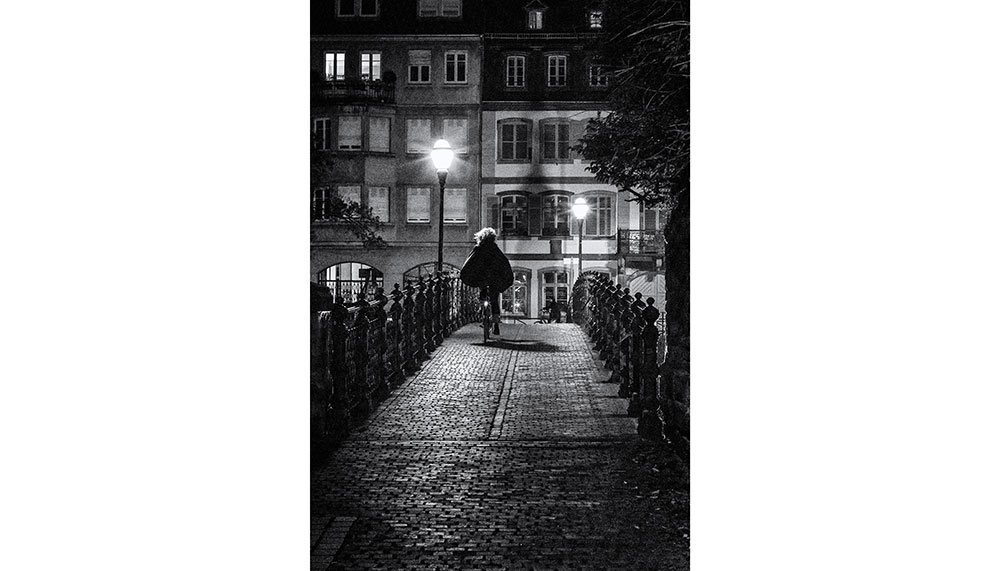

Tan’s irrepressible style shines through here, in photographs that show modern life flash-frozen in time.

Would you describe your work as street photography?

No, but it’s about getting moments, colours, vibes. There’s not much difference between this and something more ‘polished’. It’s how you want to put it out there. If it’s cool, it’s cool. If it’s not, it’s just grime.

You said it’s up the viewer to interpret what they see. Would it not be better to frame the context?

I’m not out there to document anything, or tell anyone what things are, or why they’re there. If a dog [in one of his exhibited photos] is there, it’s there. There are times when documenting things in their truest form works. When I do commercial work for architecture, where you’re trying to show form and function, you have to be accurate in what you’re trying to show. In my personal work, I’m not really trying to tell anyone anything. The colours may not look like that in real life, but I choose to tell it that way. It’s a break from my commercial work, though there are certain resemblances.

Justin Ong

Ong’s travels to remote Nagaland in India yielded a series of intense portraits of the Konyak tribespeople.

Why did you decide to focus on the Konyak tribe for this series?

A friend approached me last year and he heard about Nagaland, a place with a lot of small tribes. I looked further into it, and the more I did, the more excited I got. The project got off to a really rough start, because I had North Korean and Burmese visas from previous trips, along with my journalistic work. The Indian embassy here originally didn’t want to grant me a visa because of that. I spent two weeks with the tribe. It was exactly what I thought it would be. Hard living, but I’m really happy being uncomfortable. To me, photography is about the journey there, and getting the photos.

What is it that attracts you to discomfort and potentially life threatening situations?

The more dangerous it is, the more excited I am about the subject. I used to be a photographer for the International Peace Foundation. I used to be close to the chairman. One day, I got an email from him asking if I wanted to go to North Korea with him. I said, ‘Definitely yes, that sounds awful, let’s do it’. I guess that’s always been my approach. I like photographing places that most people haven’t been to.