The owner of the 202-year-old maison speaks about his love affair with Bovet

Any writer worth their salt spends years, even decades, honing their interviewing skills. From carefully crafting questions and building rapport, to listening actively, the entire process must be finely tuned to elicit genuine truths and nuances from even the most guarded of interviewees. Then there are the interviewees who are unabashedly open—so much so they make the hours of meticulous preparation beforehand seem almost unnecessary. With these select individuals, all one needs to do is be curious, and listen.

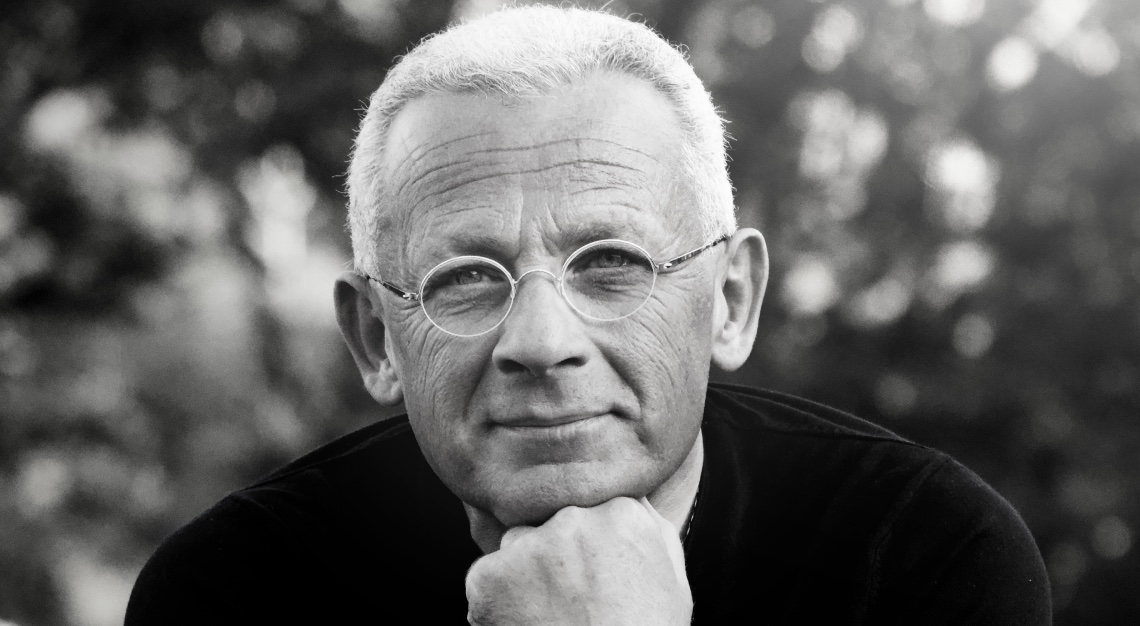

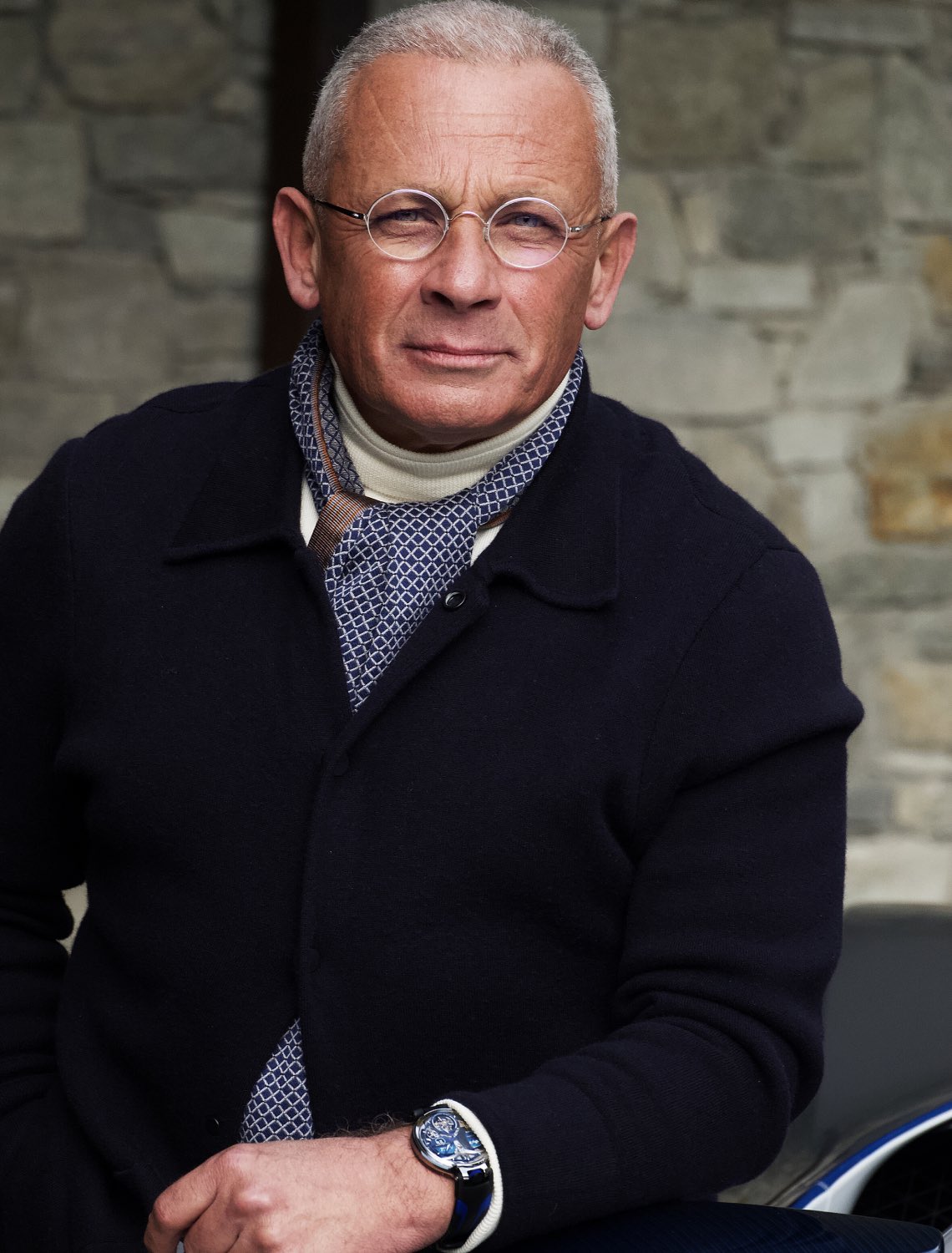

Pascal Raffy, the owner of the house of Bovet, is one such individual. What had begun as a conversation about Bovet and the art of watchmaking, quickly and organically spun into a discussion of life, poetry, and the romance of it all. It is, of course, up to the interviewer to ensure the discussion stays on track—but when Raffy gets going, it is surprisingly (and pleasantly) natural to simply sit back and revel in the conversation.

“You are very rich if you have five true friends,” says Raffy, as he pivots from an explanation of Bovet’s heritage into a discussion of friendship and arithmetic.

In this way, perhaps, Bovet and its owner share a similarity. Take a look, for example, at the Récital 28 Prowess 1, the latest triumph from the 202-year-old maison. Like Raffy himself, the 46.3mm worldtimer possesses an indisputable flair, relishing in the elaborate and exquisite.

The timepiece is mind-bogglingly complex, becoming the world’s first mechanical watch capable of accounting for Daylight Savings Time, ensuring accurate timekeeping no matter where you are in the world. The watch had taken over five years to develop but it could’ve been ready much earlier, had Raffy not been so unyielding in his thirst for novelty and complexity.

“The movement was ready in June 2022,” says Raffy. “But I told my team that we had forgotten something. We had the 99 per cent, but we forgot about the one per cent. So we had to redo the movement.”

It is this unwavering search for that extra one per cent that has led Raffy to fully verticalise Bovet’s manufacturing process since he first took over in 2001. Today, the maison makes every component of their timepieces in-house, before assembling them at Château de Môtiers, a 14th century castle that once belonged to the Bovet family.

“There is no trick with Bovet,” says Raffy. “We make our dials, our cases, and even our hairsprings by ourselves. Having everything fully integrated allows us to have all our artisans and engineers around one table. This is a luxury, and it makes a huge difference.”

Raffy may describe the maison’s verticalisation as a luxury, but probe a little further, and it begins to seem as though he deems it a necessity—especially in the context of honouring and protecting the brand’s patrimony. This commitment to the brand’s heritage is rooted in the richness of Bovet’s history, a legacy that began in 1822 when Édouard Bovet founded the maison. Not long after, Bovet had made a name for itself in the Chinese imperial courts, where its exquisitely crafted and highly decorated timepieces were prized for their precision and stunning artistry.

The depth of Raffy’s respect and reverence for Bovet’s heritage becomes abundantly clear when one looks at Bovet’s contemporary watches like the Miss Audrey Sweet Art from 2020. Sporting a dazzling dial, made entirely from hand-applied sugar crystals that have been carefully selected and treated to withstand light and heat, the timepiece is a stunning representation of the brand’s artistic legacy.

But beyond the artistry and patrimony of Bovet, what does Pascal Raffy consider to be the most important aspect of his 23-year journey with the maison?

“The human dimension,” answers Raffy.

Normally, an answer that abstract would provoke a swift follow-up question. But there’s an air of finality in the way he says it that calls for contemplation instead. Perhaps there needn’t be a more tangible answer. Or perhaps, the truth could be better discerned by reading between the lines of the 30-minute conversation, one that had proven to be gloriously human.