Spoiler alert: Notre-Dame on Fire kind of fizzles out, but director Jean-Jacques Annaud is still very sparky

Notre-Dame on Fire is not Jean-Jacques Annaud’s best film. It doesn’t even come close. And yet it’s a testament to the man’s reputation in the film industry that he was entrusted with making a movie about such an emotive event in France’s recent history.

When the 600-year-old building was alight back in 2020 and it seemed as though the entire structure might collapse, the whole of the country prepared to mourn the potential loss of one of the world’s most famous places of worship. That firefighters put their lives on the line to save the iconic structure reflects just how important the church is to many French people, and Annaud did his level best to not only highlight the significance of Notre-Dame to France and the Christian world of faith, but also the bravery of those who were prepared to sacrifice their lives to save what is, when you come down to it, just bricks, mortar and quite a lot of wood.

The film itself succeeds on some levels. It’s occasionally gripping, and the sound stage work was impeccably shot, but it fails on many others, and to a great extent this is not the fault of the director. Good films don’t necessarily have to have character development, but it helps. The problem with Notre-Dame on Fire is that most of the main characters are clad from head to toe in firefighting gear. We can hardly see their faces. They could have been anyone. How on earth do you draw out meaningful performances in your actors?

It was a problem that Annaud recognised and had to accept, and he’s keen to invoke a similar fate that befell him while shooting what turned out to be, in my opinion, one of his great films, The Name of the Rose (1986). I can’t imagine many people who would even contemplate taking on the task of making manifest on the big screen Umberto Eco’s remarkable 1980 novel, but Annaud thought he’d have a crack, did a superb job, and it may well remain as the film for which he is best remembered.

“They were all monks,” he says, halfway or so through our chat, referring to most of the main characters in the movie. “At night!”

He laughs, remembering the challenge of shooting actors clad in cowls in dim, atmospheric lighting, and comparing it to the firefighters in Notre-Dame on Fire. Character development can be quite tricky when you can’t actually see the faces of the characters you’re trying to develop.

Another failure of Notre-Dame on Fire, and also no fault of the director, is that the jeopardy had to be contrived. This was an historic event, and we all know what happened. Much of the building was saved and nobody died – I apologise if this is a plot spoiler for potential filmgoers. It’s difficult to create tension, therefore, in these sorts of circumstances.

When I meet the man at the Fullerton Hotel, I kind of want to talk about the film, and then I don’t, because I suspect that he doesn’t either. I get the distinct impression that this is not his proudest moment as a film director, so instead I ask him whether he even likes being interviewed?

“It’s an honour,” he says. “I think it’s a big privilege. A lot of people would like to be interviewed and speak about what they’re doing in life.” Annaud, however, has done a succession of the infernal things over the days leading up to, including and after the day of the screening in Singapore.

While the rest of us were watching the movie, however, Annaud was enjoying himself. He was not watching other people watching his work or looking for their reactions as the dramatic events unfolded. He was elsewhere, having dinner.

“I never attend my screenings,” he says, as though it’s the most natural thing in the world. It’s understandable, however. Annaud is a very hands-on director and goes through the editing process personally, so he claims to have seen every frame in the movie at least 2,000 times. No wonder he’d rather chow down that sit through it again. I do wonder what he ate. Should I have asked?

As something of a rarity these days, Annaud always retains control of the final cut on his films. This means that he has the last say on the end product – the film that we all get to watch in cinemas. It’s something he has always insisted on, and it’s clear that studios have trusted him. This is only right and just based on his body of work.

The Name of the Rose, Quest for Fire, Enemy at the Gates, are wonderful films – classics in their genre – leading some industry buffs to dub him the ‘French Stanley Kubrick’. Or was that just me?

“Oh, thank you,” he says, “that’s a compliment.”

Kubrick seems to have set out to make the best film in a variety of categories, from historical to science fiction to erotic dramas and dystopian crime. He made a decent fist of most. Annaud’s films are similarly diverse in subject matter, and he’s done a magnificent job on many.

He readily admits to having learnt a lot from his early career as a director of television advertisements. This is where he cut his teeth in the ’60s and ‘70s, but he was clearly destined for greater things. At least that’s what he told himself.

During his advertising career he was churning stuff out, at a rate of 60 ‘productions’ a year, but when he got a million-dollar budget for one mini film at the age of 24, he began to realise that not only was he not half bad at what he was doing, but also that people were prepared to put their money where his directorial mouth was.

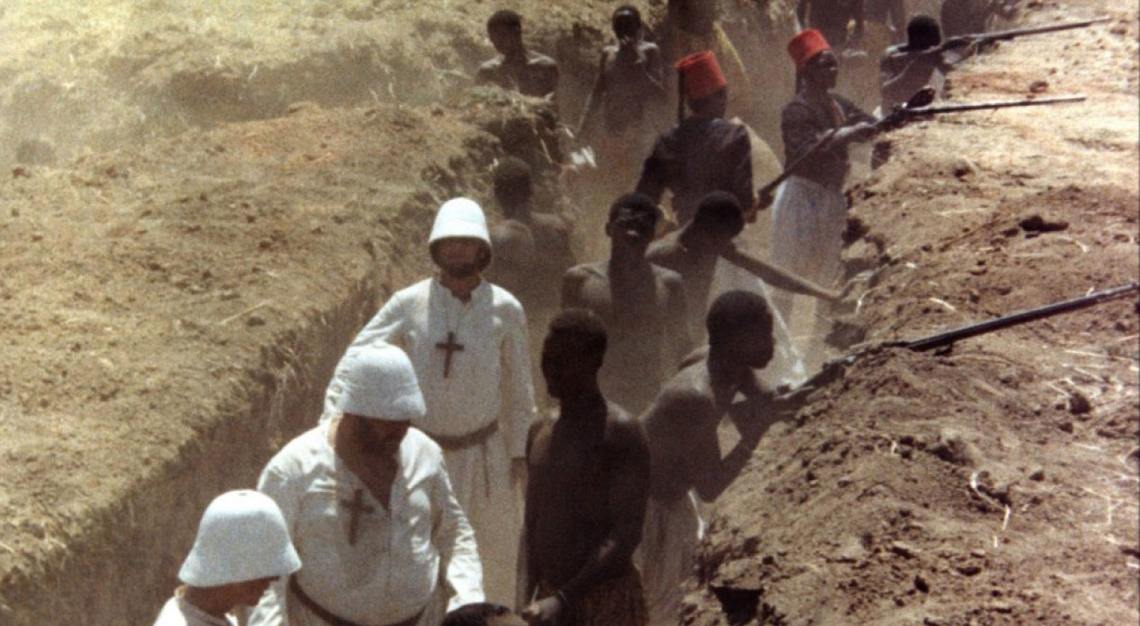

There are not many directors or producers who strike Academy Awards gold at the first time of asking, but Annaud managed it. Black and White in Colour (1976) – Annaud’s first feature film after he’d quit the meretricious world of advertising – garnered him an Oscar and catapulted him onto a most desirable list.

Not long after the film’s release, Annaud recalls being in Los Angeles, on a film lot, and was buttonholed by no less a luminary than Alfred Hitchcock, who was, presumably in between sessions of torturing actresses he quite fancied.

“Make many different films,” said Hitchcock, “but make them well.” For a young Annaud this was obviously sage advice that he took to heart, and as most movie aficionados will aver, he has rarely disappointed. He’s done so, however, in bucking the trend of ‘traditional’ French film making, which, he suggests, has always been more about art and intellectual rigour than commercial success.

“To be chic was to make a film that would not succeed,” says Annaud. “It has to be something intellectual, above and beyond what common people would like. That was what was perceived as elegant.” The implication is that a box office hit and artistic integrity are mutually exclusive, and this is something that Annaud refused to accept. He wanted to do more than produce a series of glorious failures.

Annaud, however, loved the big screen and considered it to be a suitable canvas for his artistic imagination. Spurred on by the success of Black and White in Colour, he found himself in high demand and could choose the projects he wanted to work on. In his own time. Quest for Fire (1981) was followed by The Name of the Rose, again five years later – there are common denominators here – and then The Lover (1992) which may have proved that five years between films simply wasn’t enough when you need to get it right.

It’s difficult to imagine that The Lover could have or would have been made today, in the current febrile climate of political correctness. “We’re going back to puritanism,” says Annaud, “it’s medieval… In the West we yell about Chinese censorship because it’s political, but in Hollywood it’s even worse. It’s self-censorship.” It’s very obvious that he feels as though wokeness is having a deleterious impact on creative freedom and artistic impression, but at least it’s something he didn’t have to worry about too much while filming Notre-Dame on Fire.

Annaud is 78 years old and still feels as though he has much to offer. “I have only done the movies of my heart,” he says, “and always with a combination of humour and drama.” He describes what he’s been able to do over a career spanning nearly 50 years, as a privilege.

Which of his films is he most proud of, I have to ask? “It’s like I’m a father,” he replies with a smile. “I love all my babies. Don’t make me choose.”

I wouldn’t and I don’t, but while I expect that Notre-Dame on Fire will never be considered one of his favourite children, it was a film that needed to be made, and so it was, in the trusted hands of one of France’s most gifted film directors.

Notre-Dame on Fire will come to Singapore this 8 December 2022 at select cinemas. Featured photo by Jerome Domine