With little adherence to the norms of traditional Swiss watchmaking, Krüger has developed a fresh and unique style

In Hong Kong last month we sat down for a chat with Fiona Krüger, maker of high-end, avant-garde timepieces. Krüger is Scottish but has lived in Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa, to name a few. She eventually earned her M.A. from the ECAL design school in Lausanne, Switzerland. As an independent watchmaker, few have earned the title though a truly independent artistic spirit the way Krüger has.

Krüger’s husband told me that he recently went out to walk their dog, and when he came back his wife was still talking, not realizing he had left. After getting to know Krüger at the Horology Forum in Hong Kong, I can only imagine she was waxing philosophical about watchmaking and design, or perhaps, the dire state of the world as she sees it. These topics and more stream from Krüger’s consciousness into the room with an earnest wonder and punk-rock attitude seldom found in the stuffy world of high-horology. I liked her immediately.

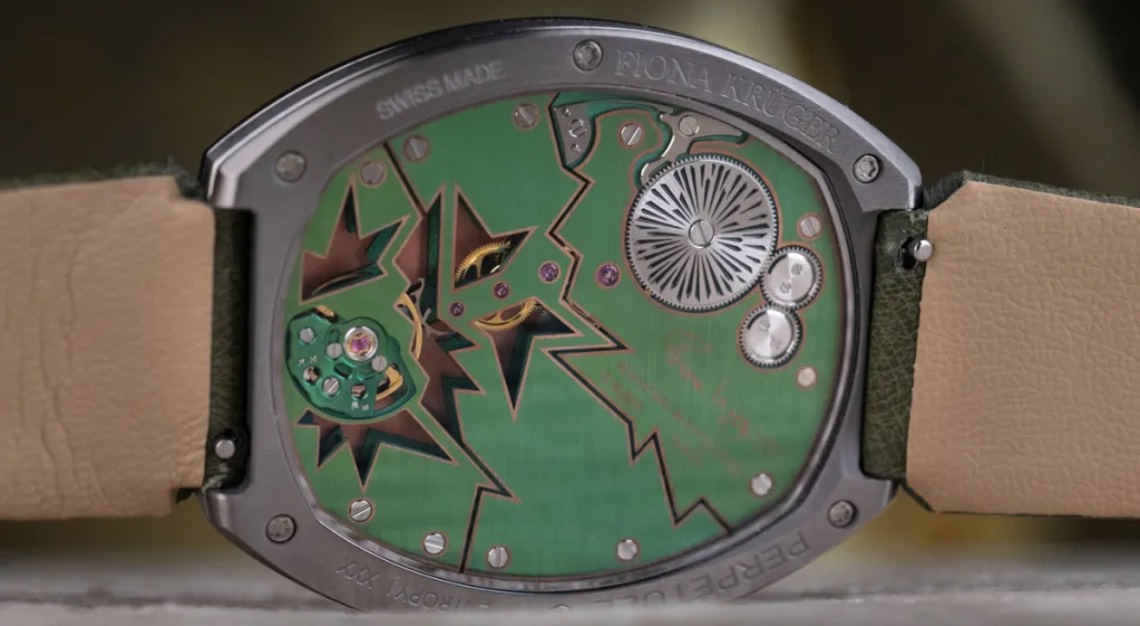

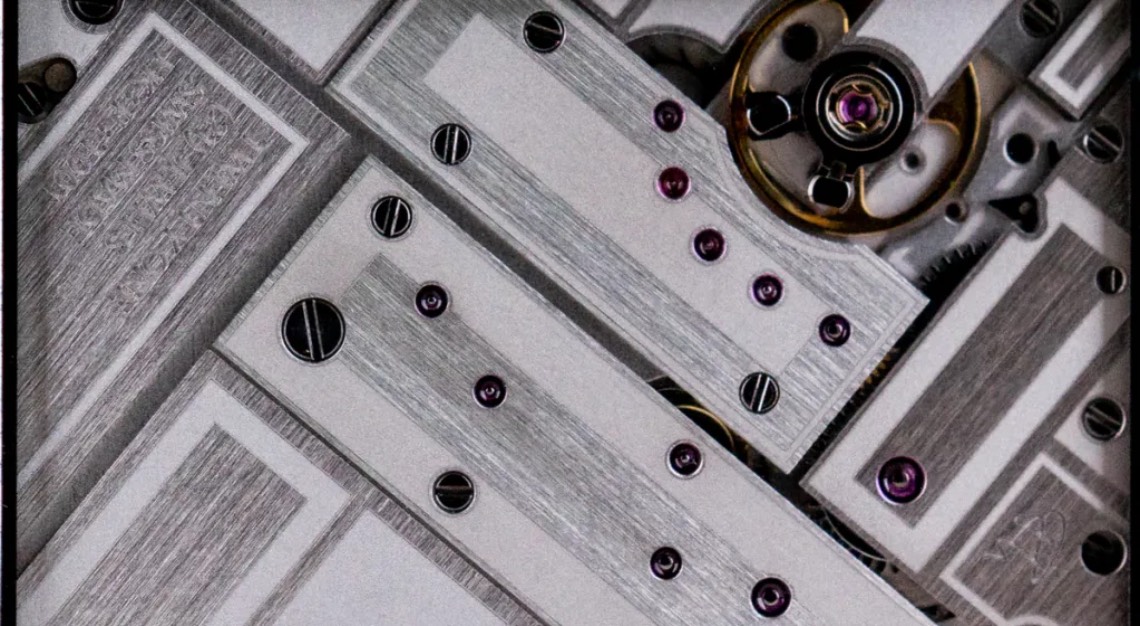

Krüger’s watches, and especially the movements she designs, reflect her punk ethos. For her, the movement is not a mere machine but a part of the watch to be designed in full accordance with her artistic concept. The results are whimsical, stunning, sophisticated, and unlike anything else in the world of watches.

Speaking of her Chaos collection, Krüger says, “If David Bowie was a mechanism, he would look like that. It’s got a punk attitude, which, in today’s world is not really that wild, actually.” However, she acknowledges, that her watches are indeed quite wild in the typically conservative realm of high-end watchmaking.

Krüger is trained in fine art and design, and—importantly—she doesn’t come from the world of watches. When asked why she approaches watches so differently, Krüger says, “I don’t really think that I’m designing a watch when I’m designing it. I just think that I’m creating an object. So, it’s not like the movement is this practical sort of beating heart that powers it. It has something to say aesthetically.”

Krüger explains that with the Chaos collection, she wanted to give the feeling of an explosion frozen in time (akin, I’d say, to Bowie’s hair when done up as Ziggy Stardust). She was inspired by Cornelia Parker’s installation called Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), which Krüger saw at the Tate Museum in London. This is not the kind of inclination from which any other watch movement I can think of has been conceived (including the Cartier Crash, which conceals its movement). Krüger’s willingness to see this highly unique movement through the technical challenges to realization behind the caseback window is a testament to her unrelenting artistic drive.

Krüger’s work sets into stark relief the aesthetic conservatism with which pretty much all other watchmakers treat time-only movements. While mechanical avant-gardists like Ulysse Nardin, MB&F, Greubel Forsey, and Urwerk resort to mechanical complexity to achieve their conceptual mechanizations, Krüger comes up with surprising designs through rearranging the layout and reshaping the bridges of simpler devices. It’s a novel approach.

“I think it’s because I’m not from Switzerland, and I don’t come from a watchmaking background,” she says. “I don’t have 200 years of heritage kind of weighing on my shoulders. I’ve been exposed to quite a different kind of thing, you know, even performance art from the ‘70s—which is absolutely mental.”

Krüger has needed to learn about mechanical technicalities, however. “With the movement side, you know where you can play and where you can’t, right? I’ll literally go: What can I move, and what can I not move…? So, I’m basically asking them to give me the framework within which I can play, and then I sort of push right to the edge of that.”

A good example of how Krüger has (literally) pushed movement design around is her Skull watch. She manages to use the mechanism itself to create the skull’s features, something no other designer of skull watches (and there are quite a few) bothered to achieve. Krüger’s mechanical scheme captures the Day of the Dead vibe she was after, this drawn from childhood memories of Mexico. In hand, the watch seems both intentional and inevitable, not gimmicky like so many skull watches.

As with many artists perusing a singular vision, Krüger shuns the business side of watchmaking: “I had no ambitions to have a company or be a brand. I still don’t. The only reason why we have a company is because we live in a capitalist system.” A familiar punk tone edged into in her voice as she went on to lodge a nuanced critique of late capitalism and its dire impact on the environment: “And that’s why I have [the business], not because I’m bothered about being an entrepreneur.”

When I asked Krüger what she thought of the brand-forward approach endemic to the watch industry, she noted that a centuries-old company doesn’t have to hold so close to its legacy. “I think it’s a very easy excuse, if I’m being a bit brutal, because . . . this notion of a brand is very, very young, and it’s a commercially minded language. [W]e talk about clients in the market as though they’re a different species. We do this kind of distancing thing with the language that we use, which I think is not very helpful.”

I asked Krüger to imagine her company 150 years into the future. Would she want those running the company to uphold and honor her legacy, just as some historic watch brands claim to be doing? Didn’t she deserve that honor?

“Once the watch is made, it’s not mine anymore,” she says. “The bit that belongs to me is the process, and that’s a bit that I love [more than] the actual object. I think what would be nice is if somebody carried on the sort of intention, which is to make something worthy of being made. It doesn’t really matter to me what it looks like.”

I suggested to Krüger that perhaps she underestimates the power of nostalgia, and she conceded the possibility. I then asked what she would do if someone came to her with an offer to commoditize her watches. Would she be comfortable with a team of people set out to convince thousands to buy a Fiona Krüger watch?

“I always think that the work speaks for itself,” she says. “I genuinely mean that. I think there’s a lot of times where people will purchase [a watch] not because in their gut they think they’re of value, but because they’ve been so bombarded that they’ve almost been ground down to then think that they are of value. It’s like you’re basically knackered from all the messaging. And you kind of go, ‘Yeah, okay.’”

Krüger did say, however, that she’d be ok with “turning up the volume on what we’re saying,” but not with “bombarding [and] brainwashing people.”

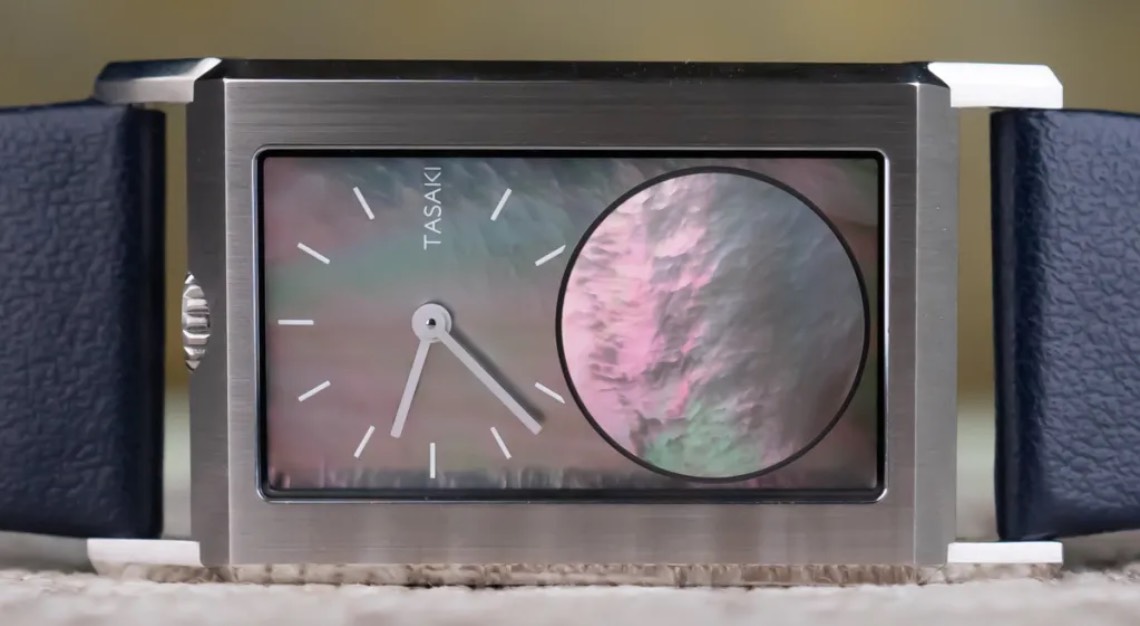

Perhaps a more subtle approach to spreading the word about Krüger’s watchmaking will come through collaboration with other brands. Krüger’s collaboration with world-famous purveyor of pearls, Tasaki, is a case in point. Despite the more placid visage of these watches—borne, perhaps, from the inherent mellowness of pearls—Krüger’s signature avant-gardism shines through in both the whimsical pearl-on-pearl sub-seconds “hand” (it’s really just a disc) and the off-set rectilinear bridges of the movement. If this latest creation is a sign of things to come, it may be that Krüger finds the volume turned up on her work after all.

This story was first published on Robb Report USA