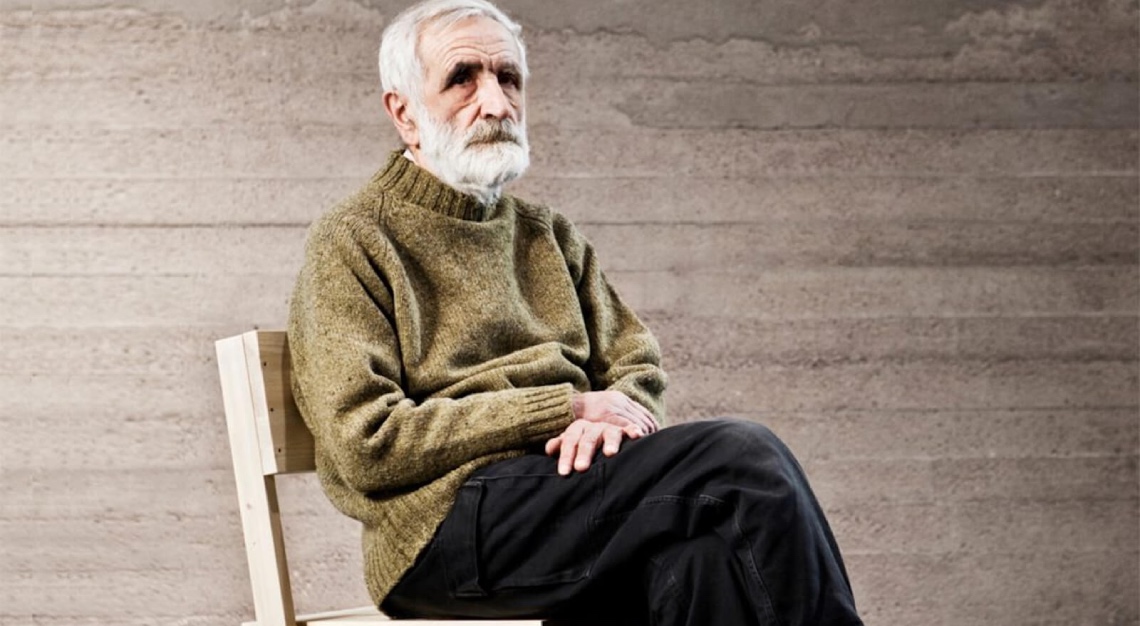

He’s been art-world famous for years, but it took a banana and some duct tape to make Maurizio Cattelan famous-famous. Here, the provocative artist shares his thoughts on creating the piece, the world’s reaction to it and the real value of art

For all the fuss made over the exponential growth of the contemporary art world – fairs and biennials popping up around the globe, finance experts labelling art an ‘asset class’, hours-long lines for Yayoi Kusama’s psychedelic Infinity Mirror Rooms and other experiential, Instagram-worthy phenomena – a paltry few 21st-century artists have succeeded in permeating mainstream culture.

Sure, the pseudonymous Banksy made headlines when he rigged a picture frame to shred one of his paintings after the hammer fell at Sotheby’s, though the media coverage focused on the destruction of an expensive object and its potential rise in value as a result. And Marina Abramović was lampooned on Sex and the City for her 12-day stint living on display at Sean Kelly Gallery, but most fans of the TV show probably assumed the boundary-pushing performance was invented in the writers’ room. Her subsequent staring contests at the Museum of Modern Art led to a dance with Jay-Z, foreheads touching, in his video for Picasso Baby, but again, recognition was the domain of insiders only. Outside the art world, Banksy’s stunt and Abramović’s celebrity following qualify merely as Warholian 15 minutes of fame.

This past December, however, Maurizio Cattelan not only joined the ranks of household names when his latest piece appeared at Art Basel Miami Beach, but got there by dint of the artwork. Outrageous, provocative, hilarious and anger-inducing, it forced its way under people’s skin. The piece consisted of a yellow banana stuck to the wall with a strip of silver duct tape. That was it. Slyly titling the work Comedian, Cattelan let everyone in on the joke, sparking a sensation on social media, breathless coverage in the national press and enough hand-wringing among art critics to fuel PhD dissertations for decades to come. Was it a brilliant send-up of art as commodity and its sheep-like sycophants? Or an empty, even cynical gag?

Days later, a self-described performance artist peeled and ate the banana with a flourish in front of stunned onlookers, dubbing the ingestion Hungry Artist, and then held a press conference, milking every second of his viral infamy. Eventually, the crowds queuing to snap selfies with the fruit (the gallery had replacements on hand) necessitated the removal of the piece. Of course, Cattelan – and his gallerist, Emmanuel Perrotin – had the last laugh, selling the edition of three for six figures.

Cattelan, 59, is no stranger to controversy or a brand of mischievous humour both within his art practice and intrinsic to his enigmatic persona. His oeuvre teeters uneasily between reality and fiction, including a lifelike sculpture of a prone Pope John Paul II, felled by a meteorite; a horse with its head plunged through a wall; and, darkest of all, a kneeling schoolboy-sized figure of Hitler apparently praying, titled Him. He once duct-taped an art dealer to a wall, suspending him a couple of metres off the ground. Another time, at a loss for what to make, he locked the gallery door and hung a sign saying, Be Right Back.

Several years later, in what a theorist might argue was a critique of the rabid trend of artists appropriating others’ work or found objects, and what a critic might say was simply creative block, he one-upped himself by stealing the complete contents of another artist’s show for his own and labelling it Another F**king Readymade – until the police threatened to arrest him for theft. When the Guggenheim Museum offered him a retrospective in 2011, he insisted on dangling virtually all of his life’s work from the ceiling of the soaring rotunda, a conceptual approach so unorthodox it induced apoplectic rages in some critics. The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl ripped not only the exhibition design, but also the contents: “(H)e doesn’t make art. He makes tendentious tchotchkes.”

For years early in his career, Cattelan dispatched his friend Massimiliano Gioni, now the respected artistic director of the New Museum, to stand in for him during interviews and lectures. Even in the 2016 documentary Maurizio Cattelan: Be Right Back (see video above), Gioni masqueraded as Cattelan, who was occasionally glimpsed but not heard. Though I have known Cattelan for almost 20 years and interviewed the (real) artist more than once, this time around he insisted on communicating under cover of email (before social isolation became the order of the day).

Conceptual artists from Sol LeWitt to Tino Sehgal have sold not objects but ideas, granting the collector or museum the right to recreate the artwork by following a set of precise instructions, which can be complex and highly specific or, as in the case of Comedian, almost comically simple. Many an arrogant fool has looked at a Jackson Pollock drip painting or an Ellsworth Kelly monochrome panel and thought, I could do that. But even the least artistically inclined or, frankly, dim-witted among us could follow Comedian’s official directions, which Cattelan relays: “Buy a yellow banana, stick it to the wall with grey duct tape.”

Cattelan didn’t affix the banana to Perrotin’s wall himself. Insurance policies mandate professional art handlers do the honours, and besides, Cattelan says, he didn’t even go to Miami to see the fair firsthand.

“Like everyone else,” he tells me, “I saw it from the Internet and I guess my reaction was very standard: amazed and a little bit confused.”

Though there’s nothing to stop anyone from picking up a 20-cent banana and a roll of tape and DIYing it, at least three collectors coughed up US$120,000 (S$167,520) to US$150,000 (S$209,400) a pop for authentication papers. Sarah Andelman, founder of the definitively chic, now-shuttered Colette store in Paris, was the first to snatch it up. The second went to an anonymous buyer and the third to Miami collectors Billy and Beatrice Cox, who promised to donate it to an institution. To outsiders, and even a few insiders, the transactions were baffling, and many observers read Comedian as an exercise in mocking collectors who will seemingly buy anything if it’s made by a brand-name artist or hawked by a persuasive enough dealer.

Born in Padua, Italy, Cattelan grew up poor. He is self-taught and says art school “probably would have curbed my enthusiasm about being an artist”. As an almost purely conceptual artist, he conjures the idea for a piece, but typically relies on fabricators to execute it (Comedian being an exception). He broke through by needling the art world much the way he did in Miami Beach, with a carefully conceived project that is easy to dismiss as a prank. He replaced the covers on scores of the influential Italian Flash Art magazine – coveted real estate for artists – with an image of his own ‘work’, a playing-card-style pyramid constructed of old Flash Art magazines. In another scheme, he solicited 100 donations of US$100 (S$139.60) each and offered to pay an artist not to make work for a year. When no artist took him up on the deal, he used the money to move to New York.

“I guess humour is relevant in every moment of life,” says Cattelan. “It is what saves you from taking yourself too seriously and keeps in mind where you came from.”

He may be a jester, but Cattelan is no fool. His goal in New York was to join Marian Goodman Gallery, one of the world’s pre-eminent galleries, known in particular for its daunting roster of intellectual Europeans, including Gerhard Richter and Thomas Struth. The first piece he showed there, in a 1997 summertime group exhibit, consisted of two tiny, taxidermied mice sitting in a lounge chair under a sun umbrella. He has been with the gallery ever since. “I don’t think of him as a prankster or a genius, but somewhere in between,” Goodman says. “He is a talented fellow.”

Posed the same choice – joker or genius – Amy Cappellazzo, chairman of fine art at Sotheby’s, replies: “Genius. But both. Genius, though.” She calls Comedian “profound, simple and hysterical” and, comparing Cattelan to gnomes of German fairy tales and Italian buffoni, or buffoons, adds: “He’s a funny clown. But actually, he’s a genius.”

The seemingly cute, lighthearted irony of many of his pieces may have masked a deeper, more serious side of Cattelan. That the drowned figure in Daddy, Daddy is Pinocchio does not belie that he is a boy; that the creature in Bidibidobidiboo is a squirrel does not negate the fact it has just shot itself in the head. Even a rapidly ripening banana speaks of death and decay. It also may be a self-deprecating acknowledgment of the oft-heard jab that his pieces are merely one-liners. Cattelan notes the banana is a “comedian’s BFF”. But who doesn’t believe comedians are the most angst-ridden among us?

Cattelan quickly gained a reputation for provocation. Between the art-world-sanctioned antics and the flair for catching the spotlight, he captured a degree of fame that eluded nearly all his peers. Lacking the oddball otherness of Salvador Dalí or Andy Warhol, he became more the merry prankster. And as with any class clown, audience reaction seemed essential to the performance.

When the Guggenheim proposed a retrospective, Cattelan’s reputation for subversiveness precluded an ordinary museum installation in the manner of piece, wall text, piece, wall text. In her appearance in Be Right Back, Guggenheim artistic director and chief curator Nancy Spector, who organised the show, says “the whole point” of Cattelan’s decision to suspend his art from the ceiling was to be “disrespectful”.

Cattelan takes issue with that assessment. “Preparing the retrospective was like writing an autobiography,” he tells me. “From my point of view, that massive hanging was an act of necessary violence to break away from my works and see them in a less sentimental light.”

Just as the presentation stunned, so did his very public announcement that he would cease art-making after the retrospective, at the age of 51. The retirement was short-lived. He returned five years later with America, a solid-gold, functioning toilet, which he installed in a bathroom at the Guggenheim. The lines for the loo snaked down the museum’s iconic ramp. Last year, during a solo exhibition at Blenheim Palace in the UK, America was stolen. The theft of an object easily seen as a symbol for Trumpian style and capitalist greed raised enough eyebrows that Cattelan denied he had engineered its disappearance.

How do I know it’s Maurizio responding?

You don’t. But I promise I’ll try my best to let you believe this is me writing.

Why did you want to do this interview by email?

Because I prefer to think twice before saying things I could regret.

Where are you?

Where I spend most of the time: at my desk, in front of my computer, standing. I found out the ideas flow better if you stay up on your feet.

When and how did you come up with the concept for Comedian?

There’s no big story behind it. I was playing with bananas for months, trying to figure out the best way to use it, either for a [photo] shoot or a work. I tried it in metal and plastic, but it never convinced me enough to be shown. I still have some not-satisfying tests on my apartment walls. Then I came out with the decision to simply present it as it is, instead of re-presenting it. And it worked well, much more than I had expected.

The venue of Art Basel Miami Beach seemed essential. It’s the glitzy fair, with as many fashion people, celebrities and partiers as art collectors. Would you have made the work for any other venue? Why or why not?

I often worked site-specifically and this was one of those cases, as you correctly guessed. But I’ve always believed that, paradoxically, the most important aspect of a site-specific, well-conceived work is that it should also be effective outside the context for which it was created originally. I’m still wondering if going viral so extensively can be considered to be ‘outside a specific context’.

Did you intend Comedian as a comment on the collectors who would buy it?

I was trying to understand something about me and the world I live in. That’s where all my works were born. I’m not able to think so much in advance, commenting on something or someone I don’t even know if it will ever exist, such as collectors buying it.

John Baldessari said he sometimes awakened in a sweat worrying that he was just making “trinkets” for rich people. You, on the other hand, seem to have a comfort level with the commercial side of the art world, as when you helped install La Nona Ora (the pope piece) at Christie’s or accepted a commission from Peter Brant. How do you feel about collectors speculating on your artwork?

Probably John put it in the best way already: Sometimes dreams become nightmares and vice versa.

What do you think about the reaction Comedian received?

It was totally unexpected in its proportions and enthusiasm. It was also broadcasted on Good Morning America. I was shocked. My mother would have been proud, in the end.

You once told me that the way a piece of yours is communicated to the public is an essential part of your creative process and the work’s existence. Did you conceive Comedian with the expectation it would go viral? Would you have considered the piece a failure if it hadn’t received the attention it did?

I’m not good at this game, like let’s play that I was a princess and you were my horse. I always risk getting confused between fantasies and reality and start to believe I’m a princess or her horse.

Were you surprised that someone ate Comedian, or were you waiting for someone to have the chutzpah to do it? Did you see it as an act of admiration, appropriation, disrespect or something else?

No, I wasn’t surprised. Comedian was gaining so much attention that it should have ended in a clamorous way. It has always happened in [art] history and it still happens today: what shocks the audience is very often subject [to] acts of iconoclasm.

Other works have provoked audience participation, including the time two Polish lawmakers rolled the meteorite off the Pope and when a Milanese man climbed a tree (and fell) in an effort to cut down your sculptures of children hanging from a limb. Are you trying to push viewers to that level of discomfort or outrage?

I believe art should change your life. You should not remain the same in front of it. Of course, I’m speaking of masterpieces, like the Sistine Chapel or the Cappella degli Scrovegni. That said, I wasn’t expecting such a dramatic reaction and it’s always fascinating for me to see how seriously an artwork can affect people’s imagination, till the point you almost mistake it for reality.

In Emmanuel Perrotin’s Instagram post announcing that the gallery was taking down Comedian, he apologised to fair visitors who would not be able “to participate in Comedian”. Do you consider it a work of relational aesthetics? Is the social interaction around it an essential element?

To a certain extent, what I think of it doesn’t matter more than what Emmanuel thinks of it. I didn’t consider it as a participatory piece in the first place, but the nature of the place where it was shown and, I guess, the nature of the work transformed it in something different from my will.

When the Trump White House requested to borrow a Van Gogh from the Guggenheim, Nancy Spector famously offered to loan it America instead. I imagine she consulted you before making the offer. Were you disappointed the White House did not take you up on it?

Nancy is a great curator, with a really sharp mind. She has the right to propose any work from the Guggenheim collection that would have been available, without consulting me at all. I would have been honoured for my work to be showed outside the museum, in such a prestigious place as the White House.

How do you feel about the theft of America the sculpture? Do you harbour any hope for its return?

I only hope that whoever took it is enjoying it.

Do you see Comedian and America as linked – one solid gold, the other a cheap banana that will rot within days – but both addressing the value of art?

A work of art is never just the artist’s individual experience, but rather the thing it is in the world. It is a moral, social and practical identity, a being that is recognised by, and relates to, others. It is not merely a physical object, but a social one, too. And the more it has meaning for others than the artist, the more it is relevant. So I totally trust you about it.

After Art Basel Miami Beach finished its annual run, the hoopla died down, replaced with coverage of the Democratic presidential primaries and COVID-19. Cattelan was left, like every artist after finishing a piece, alone with his thoughts.

Are you at all concerned that Comedian gives people who already suspect contemporary art is a load of bullsh*t more ammunition to mock it?

I think it’s important to keep a discussion always open about what is art, what it should do and its ethical value, much more than its economic value. My hope is that for every [person] who thinks that art is bullshit, there’ll be one who can explain to them where the real value is.

What’s next?

Forecasts are less and less reliable, and so am I.

You’ve been called a con man and one of the greatest artists of our time. Which is it? Is it possible to be both?

It is possible to be many things. My barber always says: “We either make ourselves miserable or we make ourselves strong. The amount of work is the same.”

Is it hard to get an advantage over yourself?

It’s a daily job.