From F. P. Journe to Kari Voutilainen, these are the best small-scale, high-end watchmakers working today

The phrase “independent watchmaker” has two fundamentally different meanings. One refers to a large industrial brand that operates independently from a corporate group. These manufacturing firms are sometimes—and perhaps more accurately—referred to as an “independent watch brand” or “independent watch company.” Another meaning of “independent watchmaker” is a very small maison, atelier, or individual that practices small-scale, high-end watchmaking.

“Independent watchmaking is really when you distill this whole industry down to a single person working at a bench as a craft,” Logan Baker, senior editorial manager of Phillips, tells Robb Report. “It’s someone that’s building a product for a person. And that’s what the best independent watchmakers do. They’re putting their heart and soul into what they view is the most ideal, the most perfect mechanism and that can take its form through more creative designs, or pioneering mechanics. It just really depends on where that watchmaker wants to take their product.”

It is these small, high-end independent watchmakers we are celebrating here, the masters of the craft, design, tools and technology that drive today’s high horology. From well-known masters like Philippe Dufour, F. P. Journe, and Kari Voutilainen to up-and-coming makers such as Japan’s Naoya Hida and Hajime Asaoka, China’s Qin Gan, and watchmaking duo Petermann Bédat, we take you into the micro-worlds of the 25 best independents working around the world today.

Some firms are larger than others, of course. There’s the single person working alone like Asaoka, and then there’s a firm like Moritz Grossman employing roughly 30 watchmakers in Germany. But none of these watchmakers produce very many watches each year—some vanishingly few, none more than a few hundred—and all are working at the highest level.

Regardless of their size (and perhaps because they are small), when aficionados speak of independent watchmakers, it is often with a reverent, even awe-struck, tone. Collectors almost universally agree that a small atelier creating exceptionally well-crafted watches simultaneously honors horological tradition while pushing watchmaking into the future. Some collectors regard independents as preservationists protecting traditional watchmaking from extinction, while others consider them mavericks pushing horology toward unseen horizons. They have also come to revere independents as a more unique alternative to larger and more traditionally esteemed high-end brands.

However, these two impulses—one toward the past, one toward the future—are almost always intertwined. As a result, independent watchmaking can take any number of mechanical and aesthetic directions, resulting in wildly different watches. For centuries, mechanical watchmaking sat at the bleeding-edge of human technology. In our AI-driven world, our nostalgia can cause us to forget that what seems quaint today was the futuristic wonder of yesteryear. So, we’d be mistaken to arbitrarily reject makers using digitally driven multi-axis CNC machines, 3D printers, and CAD software as integral to their high horology. These tools have become as much a part of the independent watchmaker’s workflow as the foot-driven polishing wheels of the 18th-century or the electronic guilloche machines of the 19th. But the handcraft is always involved, and it’s what you see in the end.

While these watches are invariably quite expensive, Baker points out that, “There is no real considerations of commercial business.” In other words, no one heads into independent watchmaking to get rich, which may seem to contradict the amount of money one can imagine some of these folks have earned over the years. The path to this kind of success often comes after years of financial struggle—not unlike that of a painter or sculptor. Some well-connected and informed watch collectors seek out the unknowns before they blow up, just as art collectors scour the small galleries for works from rising talents. Whether that impulse is driven by a profiteering motive, a love of discovery, or the dream of owning something special before it’s too expensive isn’t a question we can answer, but we can assure you our list will whet many appetites. Indeed, this list contains some living legends, and others who may very well follow in their footsteps to become legends of 21st-century watchmaking.

Below are the 10 best independent watchmakers working today.

Armin Strom

Born and raised in Burgdorf, Switzerland, watchmaker Armin Strom opened a workshop and retail location there in 1967. He quickly established himself as a master at skeletonisation — the removal of material from components such as bridges and dials in order to expose the timepiece’s inner workings — which he would hire out to brands as that technique gained in popularity. In 1984, he presented his wares at Baselworld for the first time; in 1990, he won a Guinness World Record for producing the world’s then-thinnest skeletonized watch.

In 2006, with Strom nearing retirement, he decided to sell his business to two young men who had frequented his workshop as boys, Serge Michel and Claude Greisler. Armin Strom AG was thus incorporated in his honor, with the boys realizing their childhood dream of owning and operating a watch company. Michel, a passionate watch lover and Greisler, a dedicated watchmaker with eight years of schooling, were committed to shepherding the Armin Strom name into the future with reverence and care.

In 2009, the Armin Strom brand opened its first dedicated manufacture in Biel/Bienne, which afforded it the ability to design and develop timepieces in-house. That same year, the company debuted the ARM09, its first in-house movement, within the One Week Collection at Baselworld. This highly skeletonized watch bridged the gap between Armin Strom’s personal creations and the fresh, highly contemporary marque that would continue on using his techniques. In 2014, Armin Strom debuted the Skeleton Pure, realizing a dream of creating a skeletonized watch entirely in-house. With its PVD-coated bridges and dual barrels, this compelling timepiece won a Red Dot design award in 2015.

The following year saw the company release its Mirrored Force Resonance — powered by the in-house cal. ARF15, this dual-regulator timepiece was designed to vastly improve chronometric precision by means of a Resonance Clutch Spring, which connects two escapements visible via the dial. In 2018, the brand birthed the Dual Time Resonance, the inaugural watch in its Masterpiece collection. Using the principle of resonance to display side-by-side time displays, this traveler’s watch brings together the brand’s various disciplines — skeletonisation, resonance, decoration, etc. — together in a single timepiece.

In celebration of the modern brand’s 10th anniversary in 2019, it released its second Masterpiece offering, the Minute Repeater Resonance. Offering a repeating complication coupled to a movement regulated via resonance, this world-first timepiece validated the company’s experiments in dual-oscillator design. A year later, Armin Strom debuted the System 78 Collection with the Gravity Equal Force, an automatic watch meant to offer a more affordable entry point into the brand’s distinct take on haute horlogerie.

Today, Armin Strom offers 10 distinct models within three collections, which are powered by 24 different calibers. In harnessing the savoir faire of its founder, the company is paving the way for contemporary high-end watchmaking of the highest order.

Simon Brette

It wasn’t all that long ago that Simon Brette was a young watchmaker working at MB&F designing some of the company’s more complicated and wildly avant-garde pieces such as the LMX, the HM9 Sapphire Vision, and the HM10 Bulldog. By 2021, he ventured out on his own to do freelance work for watch brands big and small, but not long after he found it was an inevitable calling to work on his own business. His debut timepiece, the Chronomètre Artisans Subscription, was an instant hit and it’s not hard to see why. At first glance, its case design is relatively traditional, a far cry from the bulldog-shaped horological wonders at MB&F. But upon closer inspection, its asymmetrical layout, exaggerated Breguet-style hands, and absolutely riveting 3D-engraved mosaic dial called “dragon scales,” looks unlike anything on the market and when you see one in the wild it surely stands out as it did when we spotted one on the wrist of a well-known collector at this year’s Rolliefest. That piece, limited to just 12, sold out and the waiting list for the production series is said to stretch into 2028.

One thing he did take with him from his former employer Max Büsser, is a penchant for promoting the artisans who help him create his coveted watches (something bigger brands like to keep secret). He lists them on his site and even creates pamphlets to hand out to share with others the faces behind the brand. They include his master engraver behind the dragon scales creation, Yasmina Anti; Damien Genillard, a second-generation finisher; and Barbara Coyon, an expert watch decorator, to name a few.

His sophomore debut created more work for this crew of creatives and was a riff on the Subscription piece that propelled him into the spotlight. It came in titanium on a green leather strap in a run of less than 99 pieces (a figure quoted on Brette’s website) and, naturally, sold out. Another edition in rose gold debuted in 2024. Get in line.

Greubel Forsey

When English watchmaker, Stephen Forsey, and French watchmaker, Robert Greubel, walked into Baselworld—at the time, the largest watch fair on the planet—with their Double Tourbillon 30°, it caused a sensation. The crux of the piece was a tourbillon with a cage rotating in four minutes and an interior cage (containing the balance spring and spring assembly inclined at an angle of 30° in relation to the first cage) making a full rotation every 60 seconds. The highlights of the watch—the tourbillon engineering, chronometric performance, and high-end finishing—would all become hallmarks of the brand.

Greubel Forsey’s pieces are known not only for these signature elements, but also an unusual blend of horological fireworks in, typically, sizeable cases to properly show them off (although in line with current trends, sizing has come down on its more recent models). Nevertheless, the duo’s commitment to traditional watchmaking shines through in its meticulous execution and steadfast approach to doing as much of the process by hand or on old-school machinery as possible.

This juxtaposition between old and new extends to Greubel Forsey’s manufacturing facilities in Switzerland’s La-Chaux-du-Fond. The site was built around a run-down 17th-century farmhouse, which was purchased by the company in 2007 and opened in 2009. Outside, the structure now appears to be an angled glass building emerging from the rural knoll on which it is perched—an obvious nod to its inclined tourbillons. Upon entering the facility, however, you can still see the remnants of the old farmhouse which cleverly ties together the old world of watchmaking with the new. Some days, you might even spot sheep grazing atop the glass structure’s grassy roof. It is, without a doubt, one of the most interesting manufactures in the region.

The company has recently undergone a leadership transition with plans to create more watches with fewer collections at lower price points. The latter is relative, of course, as Greubel Forsey’s timepieces largely cost around almost US$700,000 and now are moving into the under US$420,000 range. With its CEO, Antonio Calce at the helm since 2021, Stephen Forsey and Robert Greubel have stepped out of the spotlight to focus on what they do best…watchmaking, while Calce aims to expand the grounds of the manufacture and take the company to the next level. Again, it’s all relative at this watchmaking house, which was only making 100 watches per year for two decades until Calce took it to 200. His goal is to eventually get that number to 500, but with that figure spread around global markets, spotting one in the wild will still be a phenomenon.

Grönefeld

The first thing a visitor to Grönefeld’s website sees is a banner across the homepage announcing that the brand is oversubscribed. “Sorry, we can’t take new orders until further notice. We are now processing the overwhelming amount of reservations we’ve received after the launch of our 1969 DeltaWorks and 1941 Grönograaf. Thank you for your patience and understanding.”

Bart and Tim Grönefeld, aka “The Horological Brothers,” founded their brand in 2008, in Oldenzaal, the Netherlands, but it took until 2016, and the release of their third model, the 1941 Remontoire, a GPHG-award-winning wristwatch with a constant force mechanism, to attract the kind of attention that’s kept their workshop buzzing.

“The interesting feature of the Remontoire is on the dial side — every eight seconds it turns,” says Kathleen McGivney, chief executive of the collectors organisation RedBar Group and an ardent Grönefeld fan. “You get to see a little bit of the mechanics on the dial side and that’s very appealing to watch nerds like me.”

McGivney also cites the brothers’ sought-after Grönograaf as a quintessential example of their superior finishing, which she extolled in a love letter to the Remontoire on the RedBar site.

Rapkin couldn’t agree more. “The brothers have been around the block doing finishing work for everyone you could possibly imagine,” he says. “When you picture in your mind an haute horlogerie timepiece that’s been finished to the nth degree, it’s not improbable that it has been finished by Bart and Tim Grönefeld. “Yet their gravitational pull is very much tied to them as people,” Rapkin adds. “They’re two guys who are obsessive about their finishing, but they like to drink beer, and cycle, and they’re extremely warm and accessible.”

F. P. Journe

Few modern independent watchmakers have been as hot as F.P. Journe in recent years. In 2021, during the height of pandemic watch mania, Journe’s popularity reached a fever pitch. On November 6 of that year, the charity auction Only Watch set a record for Journe with the CHF 4,500,000 sale of the F.P. Journe x Francis Ford Coppola FFC Blue, which became the maker’s most expensive watch ever sold—a record that stands to date—and, at the time, it was also the record for any independent watchmaker. A day later, Phillips sold a Chronomètre à Résonance Souscription for CHF 3,902,000—the most expensive F.P. Journe watch ever sold on the secondary market, and was part of a set of historically significant timepieces by the maker—all of which were first series—that raked in over US$10 million in total on the auction block. The tone was set and since then, getting your hands on a Journe timepiece has become increasingly difficult. The watchmaker has been consistently sold out of timepieces with waiting lists long enough to require financial planning well into the future should you put your name down.

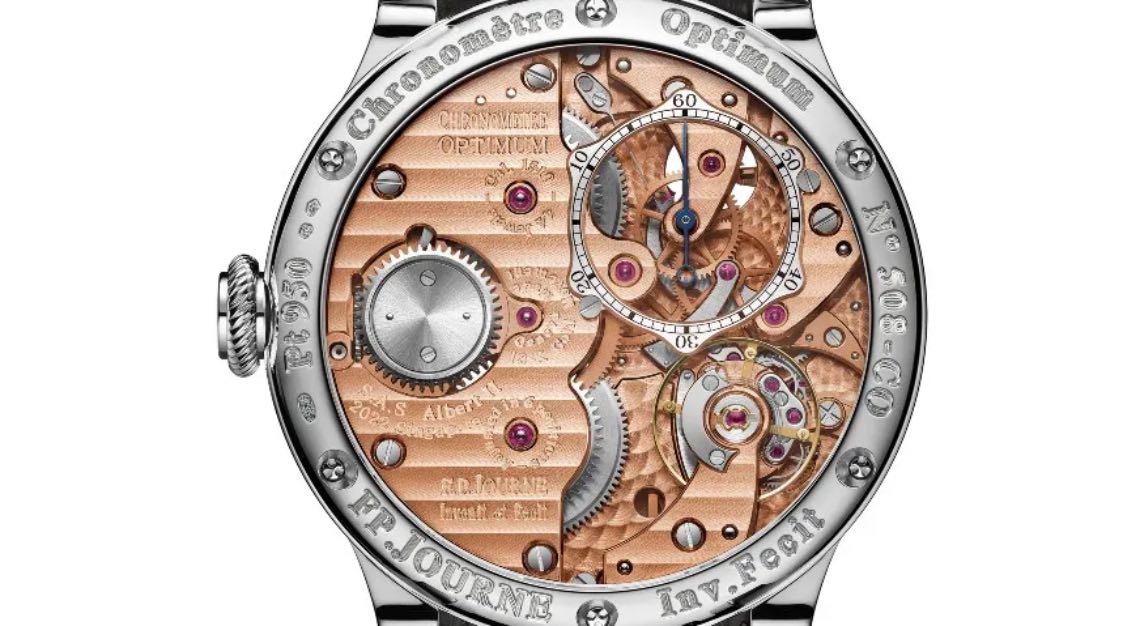

Master watchmaker, François-Paul Journe, however, has been honing his craft for decades. Before he founded his namesake brand 25 years ago in 1999, his journey into watchmaking started under the tutelage of his uncle Michel, who restored clocks by ancient watchmaking prodigies like Antide Janvier and Abraham-Louis Breguet. (Many of the truly gifted independent makers perfected their craft by restoring old, and often historic, pieces.) Both Janvier and Breguet inspired Journe when he began his company. In fact, it was while he was fixing a double regulator by Breguet in 1982 when he first started toying with the idea of putting a similar system in a wristwatch. But it wasn’t until 1994—a time when he was making custom timepieces—that he would revive the idea and begin work on what would become his most recognized piece, the Chronomètre à Résonance. The first model debuted in 2000 and was the first wristwatch to achieve natural chronometric resonance through dual movements that synchronise themselves for greater accuracy. To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Chronomètre à Résonance, Journe updated the movement to add two constant-force mechanisms for even more improved accuracy.

Journe’s legacy, however, includes many masterful models beyond the Résonance such as the Chronometre Bleu, Tourbillon Souverain, Répétition Souveraine, Octa Automatique Lune, and the incredible Astronomic Souverain, to name just a handful of his hits. Some of the signature characteristics of F.P. Journe watches include a distinctive dial layout that somehow maintains a traditional and sophisticated tone; the use of materials like tantalum, platinum, and even jade; striking salmon dials; and 18-karat rose gold movements. Of all the independent watchmakers, Journe’s production (while still tiny in comparison to bigger brands), is among the largest making roughly 800 to 900 watches per year.

Christian Lass

While studying mechanical engineering in university in Copenhagen in 2002, Christian Lass came upon an old copy of “Watchmaking” by George Daniels, the late British master watchmaker’s seminal work on horology. Enrolling in Denmark’s lone watchmaking programme, he learned to repair parts and service movements, but found this work unfulfilling. Undeterred, Lass apprenticed with fellow Danish watchmaker Søren Anderson at his atelier, learning about the restoration of old clocks and watches. Meeting legendary watchmaker Vianney Halter, he later traveled to Switzerland to work for him, spending four years learning how to craft a watch from scratch.

It was while working for Halter that Lass met Philippe Dufour, who alerted him to an opening in Patek Philippe’s museum. Unaware that he would be the museum’s sole watchmaker, he landed the job in 2009 and spent several years restoring watches and studying the past 500 years of horology. Striking out on his own in 2018, Lass established his eponymous brand and workshop in order to realize classically-inspired creations of his own imagining. Much like Philippe Dufour and Rexhep Rexhepi, he focuses on beautifully finished time-only pieces, the first of which is the 30CP.

The 30CP, which debuted in 2021, is a premium piece of haute horlogerie inspired by antique English clocks. The hand-engraved, multi-layered dial with a frosted center and a nameplate is hand-engraved by his wife Hannelore, a master engraver who has worked for Patek Philippe, Van Cleef & Arpels, and Vianney Halter.

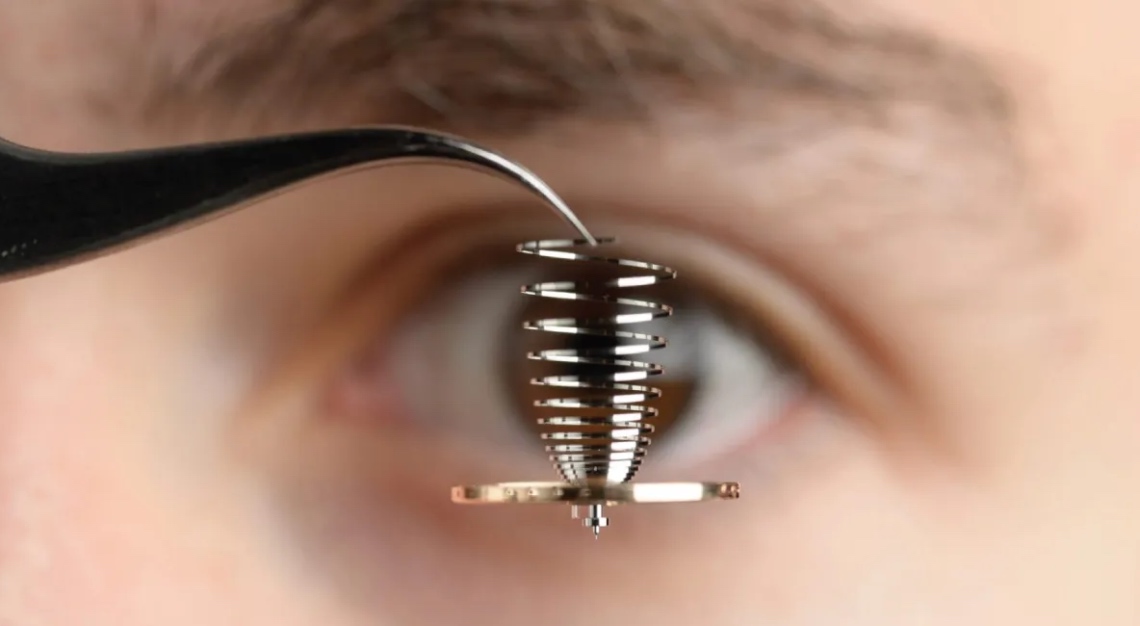

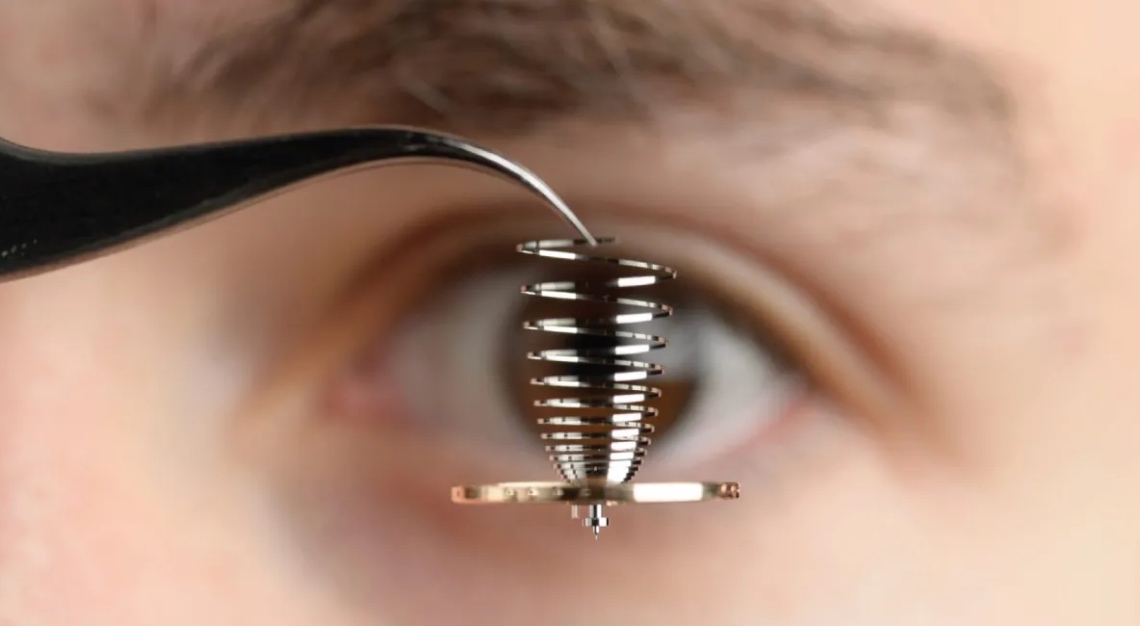

The hand-wound movement is no less impressive: The balance spring, inspired by sprouting leaves, is surrounded by engraving, while a special adjustment system inspired by 19th-century Breguet marine chronometers uses a ruby ball and several screws to allow the bridge free movement. This system, which regulates the hairspring’s accuracy, is unique and time-consuming to create: Indeed, building five prototypes consumed a year of Lass’s time, and with a promised run of 50 pieces, he could be seeing little of the sun as he toils away in his workshop for the next decade.

The dial, case, and majority of the 30CP’s movement are fashioned by Lass himself — in fact, it’s only the wheels of the going train that aren’t made in his atelier. Fashioned from German silver, the dial is paired to an 18K gold case in one of three colours, which itself measures 38mm in diameter by 11.5mm tall. With a growing chorus of watch world approval backing his handsome, vintage-inspired creation, Lass is already poised to become a horological darling of haute horlogerie collectors everywhere.

Petermann Bédat

When Gaël Petermann and Florian Bédat launched their eponymous company in 2017, a decade after meeting at watchmaking school in 2007 followed by stints at A. Lange & Söhne and the restoration department of Christie’s Geneva, they could hardly have realized how fast their careers were going to take off. When Robb Report profiled the duo in 2021 as “Ones to Watch” in the Best of the Best issue, they had just one watch under their belt. The US$66,000 Ref. 1967 was sold in a limited run of 10 pieces in 18-karat white gold and 10 pieces in 18-karat rose gold at US$66,000 each, which sold out in two weeks and created a three year and counting waitlist for future pieces. Many watchmakers toil for decades before achieving success, but the landscape for new watchmakers has notably changed in the last decade and certainly since the pandemic so their path to success was much quicker than their predecessors.

They were anything but one-hit wonders. Their second release came in 2023, five years after their debut model. The platinum Ref. 2941 monopusher split-seconds chronograph with a jumping minute counter was even more impressive with 339 components, an exceptional movement, and beautiful design. It’s shimmering platinum and sapphire dial was manufactured by the respected Comblémine manufacture. Limited to just 10 pieces, the production of this 38.6 by 13.7 mm timepiece is half that of the first and cost CHF 243,000 each. Like their premier Ref. 1967, the 2941 is likewise sold out. Having just entered their 30s last year, you can expect to see this company flourish.

Roger Smith

Born in Manchester in 1970 and raised in Bolton, England, Roger Smith — much like Philippe Dufour — was not a promising student. However, also like that famed Vallée de Joux watchmaker, Smith proved a talented craftsman. After disassembling and reassembling an old clock, his father enrolled him in a watchmaking course at the British Horological Institute in Manchester, where he excelled, and where he first met a visiting watchmaker by the name of George Daniels. Taking a weekend job at the local branch of Mappin & Webb, Smith worked on carriage clock repair, and was eventually offered a full-time job at TAG Heuer upon finishing his three-year program at the BHI. Writing to Daniels and asking to become his apprentice, Smith was rebuffed; undeterred, he set about making his own pocket watch.

Setting up shop in father’s garage, Smith got to work, eventually handing in his notice at TAG Heuer to focus full-time on his handmade timepiece. Outfitting his timepiece with a tourbillon, he proudly took it to Daniels at his workshop on the Isle of Man, where he was, once again, swiftly rebuffed. Rather than give up, however, Smith returned to his workshop, determined to impress the older watchmaker. This time, after five years of toil, Smith presented his tourbillon-equipped perpetual calendar pocket watch to Daniels; impressed, Daniels declared him a true watchmaker, and offered him an apprenticeship six months later to work on his Millenium wristwatch project. The symbiotic relationship was a dream come true for Smith, who worked with Daniels until completion of the project around 2001.

Realizing that wristwatch collecting was eclipsing that of pocket watches, Smith began preparations to build his own. However, the road wasn’t an easy one — wristwatch movement components are, after all, an order of magnitude smaller than those in pocket watches. Taking inspiration from the rectangular A. Lange & Söhne Arkade, he built a run of timepieces, the Series 1, with retrograde calendar movements by customizing a batch of vintage calibers. Continuing to simultaneously work for Daniels, he set up shop in his house on the Isle of Man, working long hours and involving an old friend from TAG Heuer, Andy Jones. By the mid-2000s, Smith was in a position to craft a wristwatch, the Series 2 — complete with in-house movement — from the confines of his own workshop. His journey from apprentice to bona fide master watchmaker was complete.

However, Smith continued to work with his beloved teacher, creating a run of wristwatches honoring the 35th anniversary of Daniels’ co-axial escapement. In 2011, Daniels passed away, bequeathing his workshop in its entirety to Smith — a final gesture of approval for his young apprentice, now grown into one of the world’s greatest watchmakers. Today, Smith — awarded the OBE in 2018 — continues to craft some of the world’s most desirable, handmade watches from his atelier on the Isle of Man, where he lives with his family. Continuing to number his creations by series, he intends to make 10 of them; he is also working with the Manchester Metropolitan University on a nano-coating to replace traditional lubricants, and has co-established the Alliance of British Watch & Clock Makers to promote British watchmaking. With boundless energy and the utmost dedication to his work, there seems little that Roger Smith can’t accomplish.

Kari Voutilainen

Considered to be one of the greatest watchmakers of his generation, Kari Voutilainen is a bit of an outlier in the Swiss watch industry in that he is Finnish. In fact, he even completed his watchmaking school in Finland. He made his way to Switzerland in 1989, where he studied complicated watchmaking at the renowned WOSTEP watchmaking school. He was quickly thereafter brought into the fold at Parmigiani’s restoration department, Mesure et Art du Temps, where he worked on some of the world’s rarest timepieces and automatons by history’s greatest makers (Michel Parmigiani is in charge of the Sandoz family’s extensive museum-worthy collection of horological marvels).

Softspoken and humble, Voutilainen obviously prefers to be behind the bench rather than in the spotlight, but as his built his namesake company from its founding in 2002, the quiet rumblings about this watchmaker turned into a roar recently—the wait time for a timepiece can be anywhere from 10 to 12 years. (In 2017, it was approximately one year.) During the pandemic, Voutilainen told Robb Report he was spending so much time dealing with clients and orders during the day that he was having to spend all his evenings on his work bench.

As a result, he has expanded by acquiring companies—such as dial makers, case makers, and businesses specialising in guilloche—to keep pace with the demand. Still, that expansion means only about 70 watches per year. Known custom-made components, observatoire chronometers, expert movements with finishing to match and beautiful guilloche techniques, his watches have become a prized possession of seriously savvy collectors. Still, he has told Robb Report that he enjoys working on his custom creations for clients where he can still get heavily involved in the artistry of creating the timepiece (and likely, where the money still merits his time). Getting the chance to do a commission on that level with Voutilainen, who’s production series pieces have a decade-long waitlist, is an exceedingly rare opportunity.

Moritz Grossman

In the town of Glashütte, Germany, there are many exceptional watchmakers, but it is Moritz Grossman that stands out—arguably along with A. Lange & Söhne—as the kind of obsessive, high-end independent house that drives the world’s most passionate collectors into fever. Moritz Grossman was a watchmaker during the 19th century, a small workshop that fizzled out due to the often challenging cultural and political forces at play in Eastern Germany. But the history of the brand is classic watchmaking of the oldest kind. Grossman wrote The Construction of a Simple but Mechanically Perfected Watch,” in 1860, a book with a philosophy that still informs what the brand does today.

We asked watch collector and world renown photographer, Atom Moore, about his impressions of the brand. Moore collaborated with Moritz Grossman on a watch recently, and he told Robb Report that, “Moritz Gorssman, to me, is the epitome of an eclectic German independent watch brand. They bring forward technical elements and new movement architecture that might only incrementally improve the accuracy or aesthetic but with great time spent to achieve it. They, in my eyes, remain humble about these accomplishments while continuously producing extremely high quality watches. They also make the best modern watch hands that, by themselves,, identify a watch as a Moritz Grossman at a glance.”

It wasn’t until 2008 that Chistine Hutter, a watchmaker by training, secured the rights to the Grossmann name and kicked off what has turned out to be one of the most successful independent revivals in modern history. Last year, Hutter told Robb Report that, “We are a German brand, so we are different from the Swiss brands. I think we keep all German standards or Glashütte standards. And we are perhaps different—if you look at the style of our movements and the finishing, we do everything in a very classic and traditional way. Not everybody’s doing it.”

Part of that classicism is the pocket-watch influence of the movements, which are neither thin nor full of visual access. Instead, heavy thick three-quarter plates are used, which add stability to the movement, but also require a great deal of labour to assemble. Hutter explained to Robb Report that, “We look for the functionality and stability of the movement. We do not have a lot of watches that come back for [premature] servicing.”

So detailed is the finishing, that the maison is among the very few that polishes between the teeth on the gears. Philippe Dufour, who is similarly detail-obsessed, told Hutter, “Christine, you know, nobody else is doing this kind of finishing.”

Over the years, the brand has embarked on some incredible partnerships that have brought fresh perspective to the brand, most recently a watch with a bold pink guilloché dial for the Princess Grace Foundation or back in 2018, a unique online advent calendar-style auction of 24 one-of-a-kind timepieces in conjunction with Christies.

This excerpt was first published on Robb Report USA