A string of recently discovered old masters pieces have found new life in the art and auction worlds. But what effect does this have on the value of the masterpiece itself?

When he was in his early teens, Jan Six wrote in a friend’s school agenda: “One day I will discover a Rembrandt”. Today, the Amsterdam art historian and art dealer can boast of having discovered not one but two previously unknown works by the 17th-century Dutch master. Hailing from a long line of art collectors, Six grew up in the presence of several works of art by Rembrandt, including a portrait of an ancestor painted in 1654. “I was obsessed with art from an early age,” he says, and having researched Rembrandt for over 20 years, he feels he’s now able to quickly recognise paintings related to the master.

Six made his first discovery in 2014 at a German auction house selling the large religious scene titled Let the Children Come to Me, at the time attributed to ‘circle of Rembrandt’. He noticed a figure in the background that bore a striking resemblance to the young Rembrandt, which was an important clue, as he explains: “I immediately recognised him, but he was so young looking that at the time of the painting he would have been a nobody and it wouldn’t make any sense for any other artist to incorporate him in their work, unless he was the artist himself.”

The art dealer advised an investor to bid on the work, but he wasn’t the only one who had an inkling about the actual artist. Estimated between €15,000 (S$22,904) to €23,466 (S$35,827), the painting was eventually sold to Six’s client for €1.5 million (S$2.29 million). The gamble paid off as the work has since been recognised as being by Rembrandt. Having undergone four years of restoration, it will go on view at the Museum de Lakenhal in Leiden, Netherlands, in November.

Twice Lucky

Six struck gold a second time in 2016 when he noticed a 17th-century portrait in a Christie’s catalogue. The Portrait of a Young Man was attributed to ‘circle of Rembrandt van Rijn’ and had an estimate of £15,000 (S$26,864) to £20,000 (S$35,812). Six recalls he had been extensively researching Rembrandt’s early works and had noticed the artist had “this very idiosyncratic way of painting a certain type of ruff (ruched lace white collar),” adding: “While most artists were painting the lace as it was actually knitted, with endless different strokes of white paint, Rembrandt did it differently, painting the ruff entirely as a white form and then painting in the black spaces. It’s a completely different approach and of course when Rembrandt became big, people started copying him, but in the early years that wasn’t the case.”

Being almost 100 per cent sure the portrait was painted by Rembrandt, Six advised a client to bid for the work, which was secured for £137,000 (S$245,300). It has since been authenticated as a Rembrandt by Professor Ernst van de Wetering of the Rembrandt Research Project, widely considered the world’s foremost authority on the painter.

Though the two works are available for sale, Six refused to be drawn on their value, but his investors will no doubt expect to make a healthy return. The record for a Rembrandt painting at auction was set in 2009 with a portrait of a man, half-length with his arms akimbo, going for £20.2 million (S$36.1 million), while a deal brokered by Christie’s in 2015 saw the French banker Eric de Rothschild sell a pair of Rembrandt portraits to the Rijksmuseum and the Louvre for €160 million (S$244.2 milion).

The exceptional result of the 2017 sale of a rediscovered work by Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi – bought for $450.3 million (S$610.5 million) against an estimate of US$100 million (S$135.6 million) – shows how difficult it is to estimate the value of a newly attributed old master.

Pricing newly discovered old masters is extremely difficult and you need to take a number of considerations into account, says Alexandra Toscano, director of the Carlo Orsi –Trinity Fine Art gallery in London. “Obviously, there is what the artist has fetched at auction in the past, but auction is not the only barometer; you (also) have to take into account the rarity, the condition and the provenance, and how quickly it will be possible to buy something else similar. Sometimes it’s a unique opportunity, and that has a value.”

State of the Old Masters’ market

According to Blouin Art Sales Index, the old masters’ share of the auction market has been contracting for years, having peaked at 22.4 per cent of the overall market in 1991. It has declined steadily to just eight per cent in 2017, while contemporary art has soared.

Now a new generation of art dealers and auctioneers is making old masters hip again. Christie’s and Sotheby’s have each partnered with interior designers to demonstrate how old masters can be presented in a chic contemporary setting, while Sotheby’s has also collaborated twice with Victoria Beckham to promote its evening sales.

Popular culture is also helping develop a new generation of art lover for the masters. Last year Beyonce and Jay-Z filmed a music video in The Louvre, prominently featuring key works including the Mona Lisa; their video is now credited with helping the museum break ticket-sale records with more than 10 million visitors in 2018, up 25 per cent on the previous year.

According to art market research firm ArtTactic, recent statistics indicate an optimistic trend in the category. Based on a survey of 16 dealers in old masters, 63 per cent reported that sales were up over the first half of 2018 in comparison to last year, while an average of 41 per cent of sales made in their galleries in the last year have been to new clients, which for more than half of those galleries is a higher percentage than the previous year.

“Good works always find a buyer, but the market has slumped at the lower to middle range end. Yet old masters are exceedingly good value price wise compared with some prices obtained by contemporary artists and more recently we’ve been able to attract younger buyers, though it’s quite difficult,” notes Toscano, adding she has also started to notice more interest in old masters from Asian buyers.

Newfound Treasures

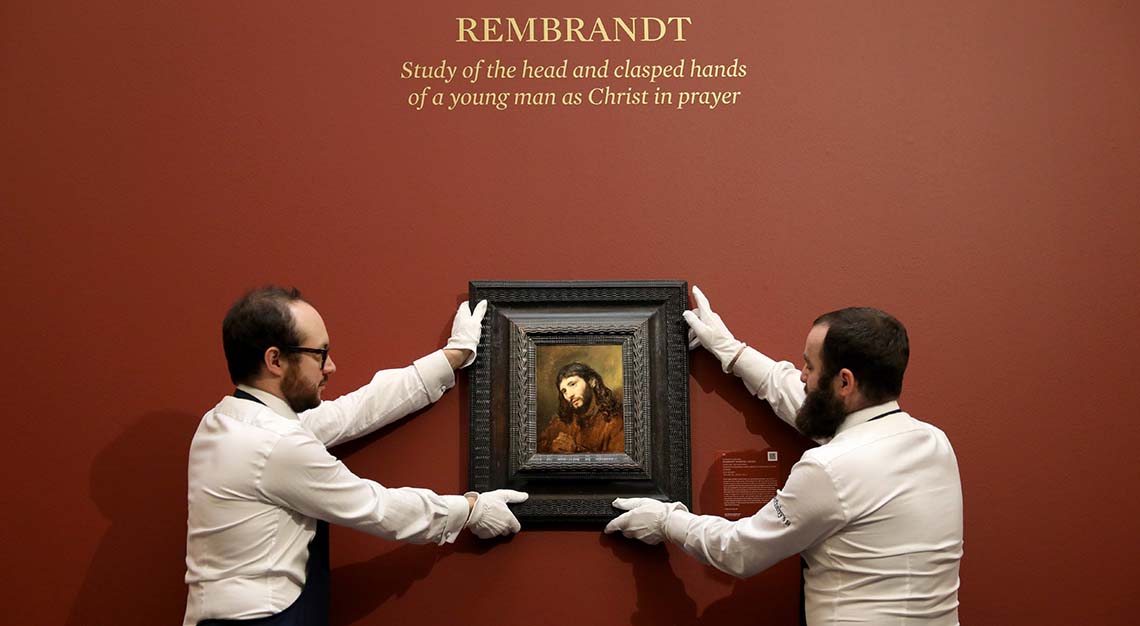

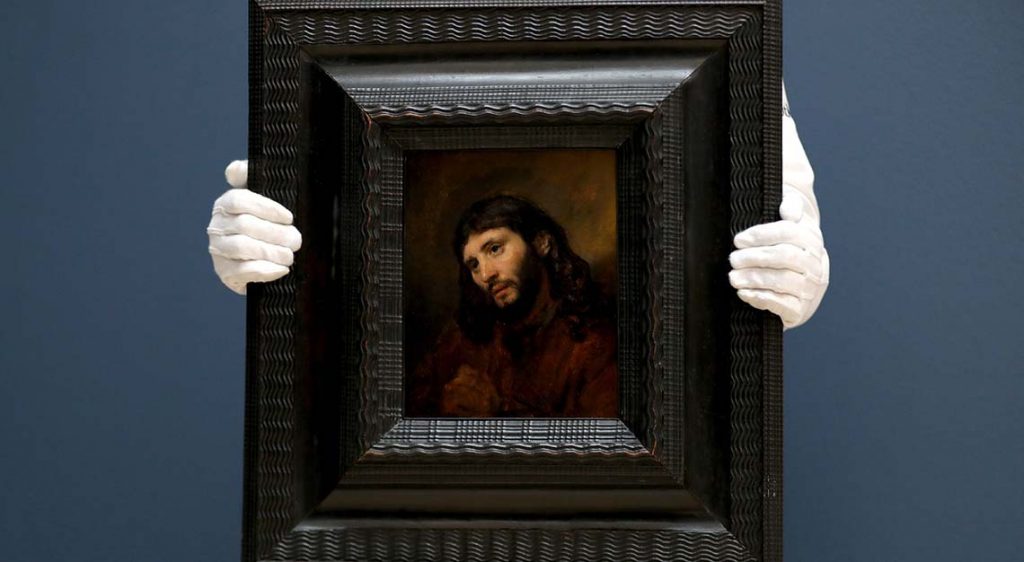

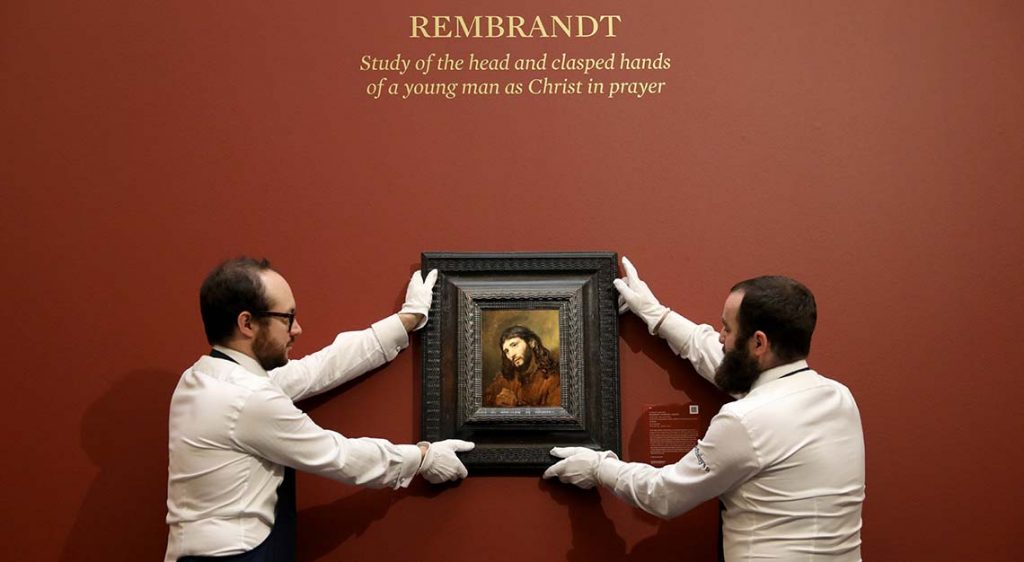

George Gordon, co-chairman of Sotheby’s worldwide old master paintings department, points out that previously unknown works or long-lost pieces do come to the market more often than one might think. This is particularly the case with old masters like Rembrandt who are especially complex in their work because, Gordon explains, where art historians had previously discounted some works as being from his students or just ‘of the period’, progress in technologies to forensically examine paintings and new scholarly studies now give a better understanding of the artist’s process and are allowing for the attribution to be changed.

Infrared imaging, for example, has become more accurate with higher resolutions, and in one case helped uncover two fingerprints, believed to be those of Rembrandt, on a little-known oil sketch, Study of the Head of a Young Man. Indicative of the growing interest in old masters in Asia, the sketch was then unveiled in Shanghai ahead of its sale in London in November for £9.5 million (S$17 million), well over its estimate of £6 million (S$10.7 million). Sotheby’s also held an extensive selling exhibition of old master paintings and drawings in Hong Kong last September.

In March, art lovers visiting Carlo Orsi – Trinity Fine Art’s TEFAF Maastricht booth will be able to discover a 1547 painting recently reattributed to Antwerp artist Frans Floris de Vriendt. Meanwhile later this year, two previously unknown works are also coming to the market: one by Leonardo da Vinci and the other attributed to Caravaggio.

Parisian auction house Tajan will offer the rediscovered work by da Vinci, which has a wide-ranging estimate of €30 million (S$45.8 million) to €60 million (S$91.6 million), at a sale on 19 June. The main drawing, The Martyred Saint Sebastian, with two smaller scientific drawings on the back, is believed to be one of eight mentioned by the artist in his Codex Atlanticus. And Marc Labarbe Auction in Toulouse is planning to offer a work attributed to Caravaggio — though not all experts agree — that was discovered in an attic in southern France in 2014.