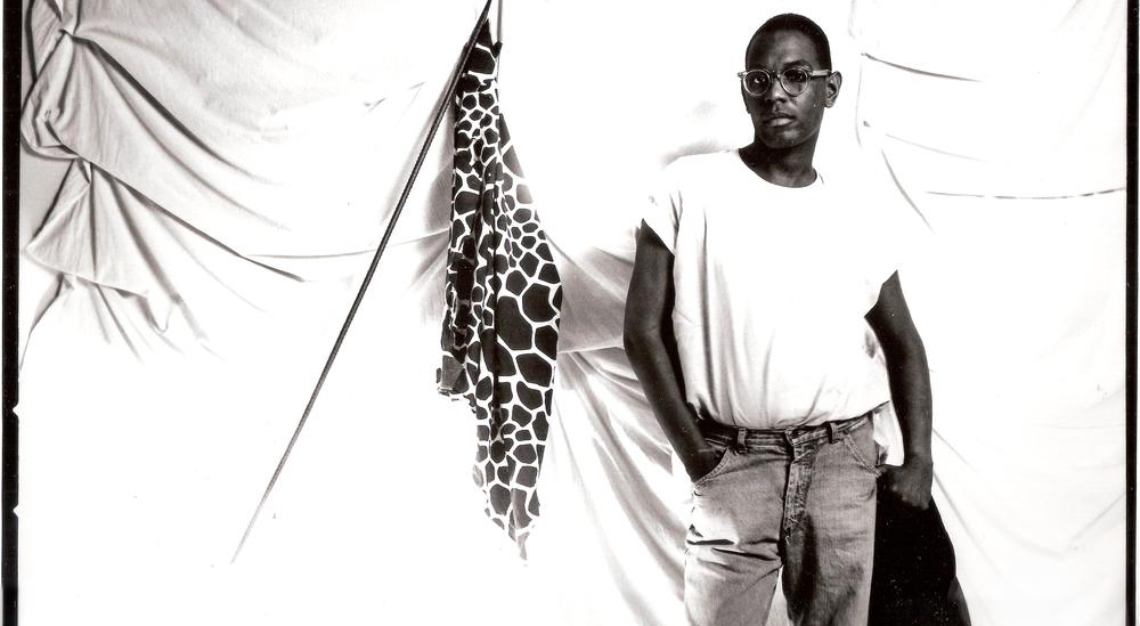

Vollebak’s co-founder Steve Tidball isn’t just selling clothes, incorporating robotics, architecture and stealth technology in his products

Fifty years from now, we might look back and be amused by the fact that the most clothes could do was to protect us from the rain.

In the meantime, 41-year-old twin brothers Steve and Nick Tidball, who launched Vollebak in 2015, are designing the clothes of tomorrow by melding science and technology. Their creations include a disease-resistant jacket that is 65 per cent copper and another made of graphene. Since the company’s genesis, the brothers have bagged innovation awards from Time, Wired and Fast Company.

Vollebak is a Flemish cycling term that means ‘going all out’. It aptly represents the energy these brothers bring to their projects. Steve talks to Robb Report Singapore about the brand and its feats and challenges.

Why Vollebak?

When Nick and I were in the advertising field, we were running in extreme races across deserts, through the Amazon and over mountains where we were duly tested by Mother Nature. Once, we had to sleep in the middle of the desert before our race and believe us, it was tough.

From that and a couple of other experiences, we realised that there was no brand innovating adventure gear that addressed such pain points. Everyone was making clothes that looked the same, used the same material and technology, and they were even saying the same things. Hence, we wanted to start something purely in adventure gear innovation.

Was your first creation a success?

Our first product was the Relaxation Hoodie, which actually launched our company. It’s a bright pink waterproof jacket that conveniently zips all the way up over your face so people know not to disturb. In the making of it, we looked into the science behind relaxation, researching more about colour theory and sound design.

The idea for it came the night before our race when we had trouble sleeping in the middle of the desert. We had nothing but clothes with us. It struck us – why not create clothing that could help us relax even in harsh conditions?

However, we soon realised that athletes were not into pink. While the idea was true to our mission, it was not for our target audience. Despite that, the silver lining in this was the feature on Jimmy Fallon’s The Tonight Show. After our pink hoodie went on air, everyone started noticing and talking about us.

In the line of business where originality is everything, how does the team keep ideas coming?

We try to build a tight circle comprising scientists, adventurers, explorers and creatives, and we talk to them all the time. Once, an adventurer friend who was descending a volcano asked us if we could make clothes that wouldn’t melt. At the same time, a scientist friend was trying to invent clothes that did just that. These types of conversations tend to lead to ideas.

Creative blocks are painful. How do you and Nick deal with that?

Our creative blocks rarely happen in the ideation phase. They often come in the development stage instead. For example, we wanted to produce a clothing with blue light for those who have to be awake for long hours, and sometimes almost instantly. At that time, blue light seemed like a great idea, but we soon realised that it was bad – it could cause cancer and potentially blind our users. So, we had to kill the idea.

As mentioned, you have had your fair share of mistakes. Could you share a bit more about some of the hardest lessons over the years?

One of the most difficult challenges was making the Deep Sleep Cocoon – a cross between a cocoon and a spacesuit that was built for missions to Mars. We did not have access to astronauts on The International Space Station (ISS) and we were not sure what we needed, so everything was based on theory.

Plus, since we are not a multimillion-dollar company and have limited resources, sometimes we have to take leaps of imagination and faith. The Deep Sleep Cocoon is a manifestation of just that.

Will Vollebak go beyond clothing?

We are looking into robotics, architecture and stealth technology. We theorise that the future will be more extreme. We believe that more of us will be exposed to fires, floods, isolation and more possibilities of deaths. Plus, with COVID-19 sticking around for a while, we would continuously rethink the concept of human interaction.

So, while clothing is one way to design for this extreme future, we recognise that there are other ways too. Because when we look at the hierarchy of human needs, we also need stable habitation, food, clothing and emotional support. And that is where our heads are at.

What does the future of clothing look like to you?

I do not think people understand the speed at which clothing is becoming increasingly intelligent and how that would affect our lives. Imagine clothes that inform you of an impending heart attack or that warn you about poor air quality.

Whatever it is, there are so many areas in which clothing will become the interaction between us and the environment, and the interface between us and our body. It is interestingly still not discussed today, but I believe our company is on the road to demonstrating the future of clothing to more people. And this revolution is coming quicker than we know.

This story first appeared in the March 2021 issue, which you may purchase as a hard or digital copy