A collection of seven distinctive treehouses, all designed and constructed with a wholeheartedly Scandinavian approach towards sustainability, have helped to put northern Sweden on the map

The 21st century traveller is certainly spoilt for choice when it comes to picking the perfect holiday accommodation. These days, you can choose to unwind at boutique hotels, wellness retreats, hideaways that are formerly owned by Italian nobles or even luxury hotels right in the heart of a city.

But the next time you travel, why not skip convention and spend the night in a treehouse? If you’re not sure where to find one, then book a flight to the quaint village of Harads to discover one of Sweden’s most famous hotels.

Up in a Tree

It’s one thing to gaze at photographs of Harads’ most famous ‘treeroom’, The Mirrorcube – a 16sqm reflective aluminum treehouse nestled benignly into the treetops – but to stand close to it in the Swedish wilderness is a marvellously surreal experience.’

“The treehouse is a worldwide concept,” says Kent Lindvall, who founded Treehotel in 2010 with his wife, Britta Jonsson. “I think the first one was made in Africa, and even today, some people still live in treehouses. Our intention here was to do something more than creative design: we wanted to connect it to nature by putting it into our surroundings without harming them. That’s important for people to be able to come and relax in the forest.”

After nearly seven years of running a guesthouse in Harads, they noticed that a treehouse built on their land by filmmaker Jonas Selberg Augustsen proved particularly popular with guests. “We’d been renting it out for two years, and when people stayed there, they’d come to breakfast the next morning, happy to have stayed high up in the tree, enjoying the view and connecting with nature. We decided it was something we could do more of.”

A fishing trip in Russia brought Lindvall into contact with three prominent Swedish architects: Bertil Harstrom, Thomas Sandell and Marten Cyren. Intrigued by his proposal to create sophisticated but environmentally sustainable treehouses, the architects agreed to collaborate by designing at least one treehouse each, despite working for competing firms.

The list grows

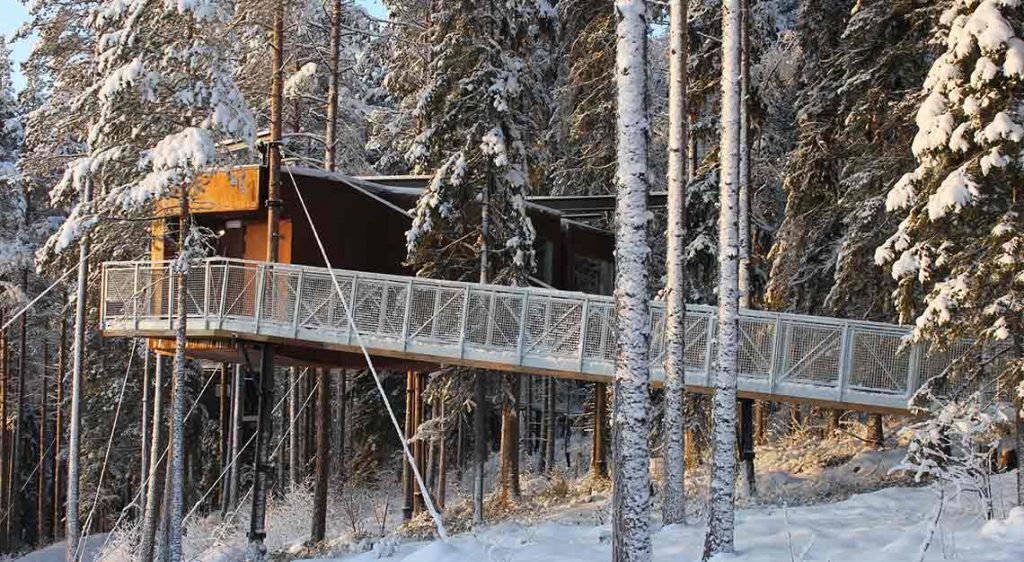

By the summer of 2010, The Bird’s Nest, The Blue Cone, The Dragonfly, The UFO, The Cabin and The Mirrorcube had all been constructed in an area of forest close to the original guesthouse.

The treehouses are suspended around four to six metres above the ground, and are connected to the supporting tree trunks with unique brackets that are adjusted every year, allowing the trees to live and grow. Each treehouse is special in its own individual way, possessing an entirely distinctive design from the other six, both inside and out. The Bird’s Nest, for instance, is camouflaged in an intricate network of sticks and is accessible only by a retractable ladder, making it a cosy retreat from the rest of the world. The Cabin – another sought-after treeroom – has a rooftop terrace that peers out towards the idyllic Lule River valley.

At the beginning of last year, Treehotel launched its newest treehouse, The 7th Room: a considerably larger and higher treehouse designed by the Norwegian architectural firm Snohetta. A net patio-cum-hammock and an underside covered by a life- sized photograph of the treetops, before the treeroom was constructed, are two of its defining features – not to mention a shower.

Most Treehotel guests share luxurious shower and sauna facilities on ground level, as installing water systems for each treehouse would have destroyed the forest grounds. This has not, Lindvall insists, deterred visitors who are used to a certain level of luxury accommodation, as evidenced by the helipad on a nearby field for guests travelling via helicopter from Lulea Airport.

“Most people know about it before they come,” he says. “Anyhow, this is another kind of experience. You can accept staying in a treehouse without a shower because that’s exactly what it is: a treehouse!”