The amazing race

It seems that every project Yann Arthus-Bertrand works on is a way for him to celebrate humanity and transmit a message of hope and optimism. A goodwill ambassador for the United Nations (UN) Environment Programme, he’s a one-man force working against man’s destructive nature. Arthus-Bertrand built his reputation as an aerial photographer with his hugely successful book Earth from Above. Published in 1999, it has sold more than three million copies and been translated into 24 languages. Its arresting images have been exhibited on the streets of countless cities around the world and seen by 200 million people. His beautiful pictures serve to open our eyes to the fact that when it comes to our planet, none of us want to believe what we already know.

His GoodPlanet Foundation, founded in 2005 in Paris, supports large-scale carbon-offsetting projects and green education programmes, and masterminded three documentaries. Arthus-Bertrand has the ability to see the big picture, showing us the beauty of the living world while raising awareness of its fragility, perhaps as the result of having looked down on creation more than anyone else in history. His aim isn’t to save the planet but to save humanity, as the planet will survive us.

Although aged 69, Arthus-Bertrand’s energy is boundless as he criss-crosses continents at a relentless pace to promote his latest feature film, Human. It premiered last September simultaneously at the UN headquarters in New York, at the Venice Film Festival and on YouTube in six languages. In the same month, his exhibition, Celebrates Life, premiered at YellowKorner, a Parisian gallery that sells limited editions of his photos. He continued his European rounds – Brussels, Calais and then Saint Petersburg – before heading off to Bangladesh to make a TV film for the COP21 UN Climate Change Conference in November. “I’m amazed by the emotion that we have created and incredibly moved by the success of the movie (Human),” he remarks. “In Brussels, we had a 15-minute standing ovation and everybody was crying. It’s a very strong movie, but it’s not because of us – it’s because of what the people whom we interviewed gave us.”

With Human, as with all his projects, Arthus-Bertrand’s subject is humanity and his goal is to spread his message of love. In the film, he forges a strong link between mankind and earth. Through a series of intimate, sincere stories of the human race that reveal our differences and similarities, we see how human development has left its mark on nature’s landscapes. He notes, “I think we need more humanity in our lives now because there are seven billion of us and there are many problems everywhere in the world: war, climate change, the economic crisis, the refugee crisis.” From asylum seekers in Calais and freedom fighters in Ukraine to workers in Bangladesh and farmers in Mali, we are immersed in their lives – their hopes, dreams, strengths and weaknesses.

“I’m a journalist and I wanted to understand why we cannot live together, so I decided to make this movie 10 years ago,” discloses Arthus-Bertrand. “For the last three years, I had been working a lot on this movie, and it completely took over my life. I love people and the more I worked on this kind of film, the more I liked it. I think this work makes me more human.” Three years in the making by a dedicated team of 16 journalists, 20 cameramen, five editors and a 12-member production crew with no fixed script, the movie entailed 110 shoots in 60 countries, 2,020 interviews in 63 languages and over 500 hours of aerial filming.

Born in 1946 to a bourgeois family of Parisian jewellers, Arthus-Bertrand dropped out of high school at 17 to work in the cinema as an assistant director and actor, before meeting his first wife who instilled in him a love for nature. Together, they ran a wild animal park in central France for 10 years, breeding lions and tigers. At the age of 30, following in the footsteps of his idol, chimpanzee expert Jane Goodall, he moved to Africa, leaving his first love to live in Kenya with his second wife and a family of lions. He met the wildlife photographer Jonathan Scott and began to use the camera to capture his observations, with the lions becoming his first photography teachers. At the same time, he made a living flying tourists in a hot-air balloon, and that’s how the two came together: flying and photography.

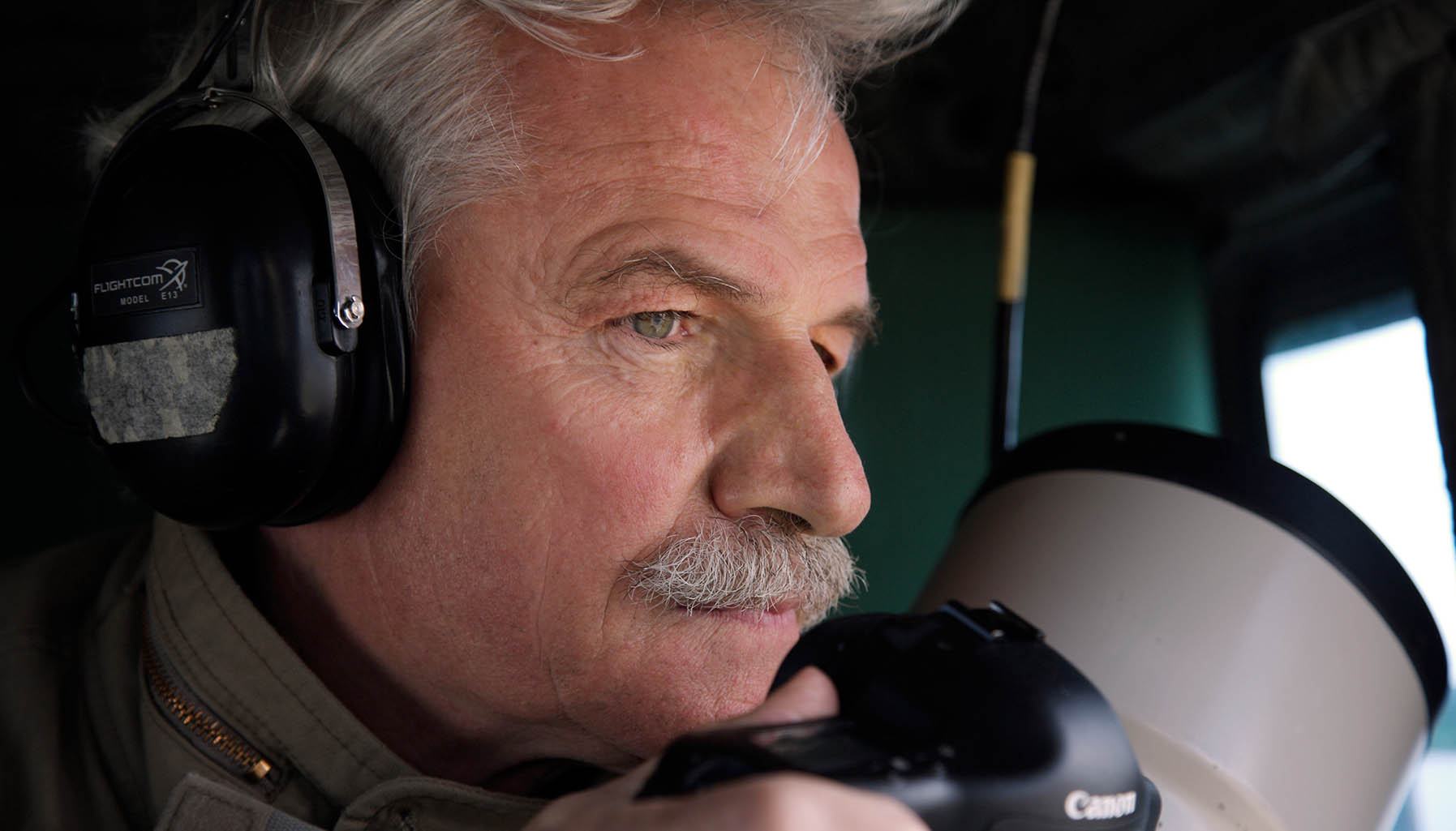

Then, as a photojournalist for National Geographic and Life, his life changed while working on assignment at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, and he decided to photograph the whole planet from above to show its beauty and man’s impact on it. Although funding was difficult to come by, for nearly two years, he flew over 80 countries in a helicopter with his camera.

Self-taught, Arthus-Bertrand improvises and relies on his instincts, sublimates the ordinary and evokes emotions from viewers to draw them in and incite them to want to understand more about the image. “There is a universal quality about beauty; in front of a vast landscape, we all share the same feeling of wonder,” he reflects. “When nature is beautiful, we are all moved by it. I aim to elicit emotion to provoke thought and the need to know more, to read the caption and learn what is at stake.”

Although he takes thousands of photos for a single report, a visit to his studio in Paris’s sixth arrondissement reveals that only a tiny percentage is retained for books, exhibitions and prints amid an archive of 230,000 images stocked since 2004.

His photos are retouched to have them resemble reality as much as possible – a process that can take anything from 15 minutes to an entire day for one image. Each photo tells a story, whether it is depicting human life such as a yak caravan in the dunes in the Indus valley in Pakistan; nature’s beauty such as the Agua Azul waterfalls in Chiapas state in Mexico; or scenes of poverty such as an open rubbish tip in Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic.

At other times, his pictures appear rather abstract, akin to paintings, such as his shots of algaculture ponds in Bali in Indonesia.

Through his work, Arthus-Bertrand’s aerial vision has taught us that we are all interconnected as pollution doesn’t respect national boundaries. Contemplating his 40-year career, he says, “I’m someone who tries to do my job the best that I can and, as I get older, I want to go to the essential, to what is important. Through what I’ve seen in my work and the people I’ve talked to, I think we’re too rich. We have to share. That’s what my movie is about.”