If you were confused about this year’s Camp-themed Met Gala, you’re not alone. And no, it doesn’t involve camo prints or huddling around a log fire

Of all the past Met Gala themes, this year’s stands apart for how esoteric it is. Camp, after all, is not typically talked about in genteel circles (much less the subject of an Anna Wintour-sponsored extravaganza), but with the first Monday of May upon us, we at Robb Report Singapore take it upon ourselves to unpack this mysterious theme.

Camp emerged in the early 20th century as a term for intentional artifice or excess, for the sake of ironic amusement. You’d be surprised by how many campy images we are surrounded by in popular imagination: from Warhol’s so-proletariat-it’s-fine-art Brillo Box pieces to The Rocky Horror Picture Show, camp lies in uncovering the good taste in bad taste, which, as we all know, abounds to no end in this world.

Camp fashion, on the other hand, traces its modern origins to the underground drag ball culture of New York, with its comically exaggerated glamour gowns and throw-caution-to-the-wind poses. Hearteningly, important fashion events like Pitti Uomo – where European menswear lads preen and peacock up a storm in the 40-degree Italian summer heat – preserve camp’s trademark over-the-top posturing in today’s fashion industry. And though much of camp fashion continues to be infused with the drag ball’s gender play, it has also gone on to subvert more than just conventional gender roles.

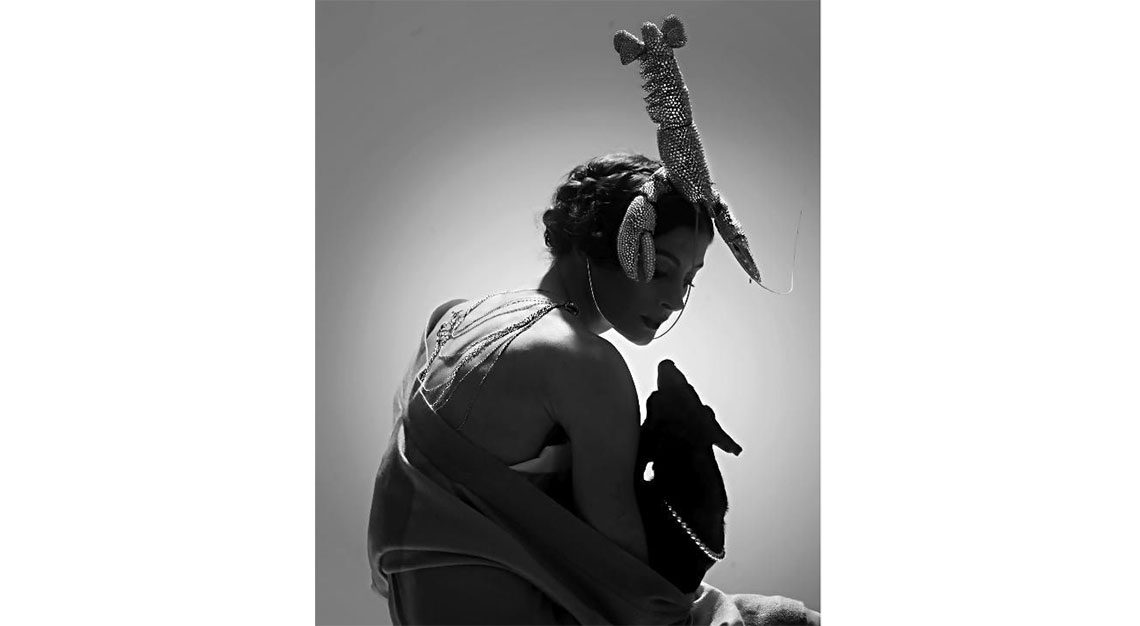

Arguably the first auteur of camp in the mainstream fashion world was Elsa Schiaparelli, who made her name conjuring up delightful base lobster, high-heeled shoe or lamb cutlet hats for moneyed Italian aristocrats. Her creations’ arrival in high society both shocked and tickled her clientele’s refined sensibilities; they delighted in Schiaparelli’s frivolous incorporation of everyday middle-class items into high fashion.

Since then, a parade of iconoclast houses have camped up their runways: Prada with ugly chic prints, Balenciaga with chunky normcore sneakers, Jil Sander with leather-as-paper lunch bags. One of my all-time favourite camp extravaganzas remains Dior Couture-era John Galliano, circa Spring/Summer 2004, throwing a madhatter Ancient Egyptian show – replete with sequinned hieroglyphics and mummy headmasks – with a liberating disregard for ergonomics or saleability.

But perhaps no brand identity is as fastidiously tied to camp as Gucci’s. When Alessandro Michele took over as creative director in 2015, the Italian fashion house morphed its look from sumptuous 90s vamp to demodé 70s nerd, which saw its runways overflow with mismatched allover prints, fey embroidered suits, and improbable frilly silhouettes. (Thus also affirming, season after season, our fake-news conspiracy theory that Michele and the costume director for The Royal Tenenbaums are one and the same.)

In many ways, camp fashion is a product of today’s cultural psyche; the very woke, boundary-breaking attitudes that have Jaden Smith don a skirt and Hermès collaborate with graffiti artists. Yet camp fashion is also a notorious magnet for accusations of cultural derision or, more damningly, for being written off as being tacky.

We once attended an outrageously witty Moschino show – think moto GP tailcoats, silk brocade biker jackets, giant bedazzled crowns – at the storied Palazzo Corsino in Florence. Upon sitting down to dinner afterwards with a well-respected fashion critic friend, we got into a full-blown bicker about her dismissive eye-roll reviews. But camp, like Hamish Bowles puts it, is “pose and performance”. Fashion, then, is at its heart all camp: the fashion show as a performance, the considered construction of a garment’s silhouette and posture, the endless subversion of the status quo with every new collection.

You don’t have to look very far for contemporary camp icons and their extravagant costumes. From Helena Bonham Carter’s mesmerising Victorian frivolity to Nicki Minaj’s bordering-on-blinding latex outfits, some celebrities, in their diverting fashion choices, habitually present the world a steady dose of subversion with a side serving of winking Internet troll.

It is perhaps only fitting then, that 2019 is the year the rarified hallways of the Met’s Costume Institute will be filled with camp couture. So when you see images of celebrities ascending the red carpet steps to join Anna Wintour’s pantheon of outlandishly dressed camp deities, remember Sonia Sontag’s closing reminder in Notes on Camp, which influenced the theme of this year’s soiree: “the ultimate Camp statement is it’s good because it’s awful.”