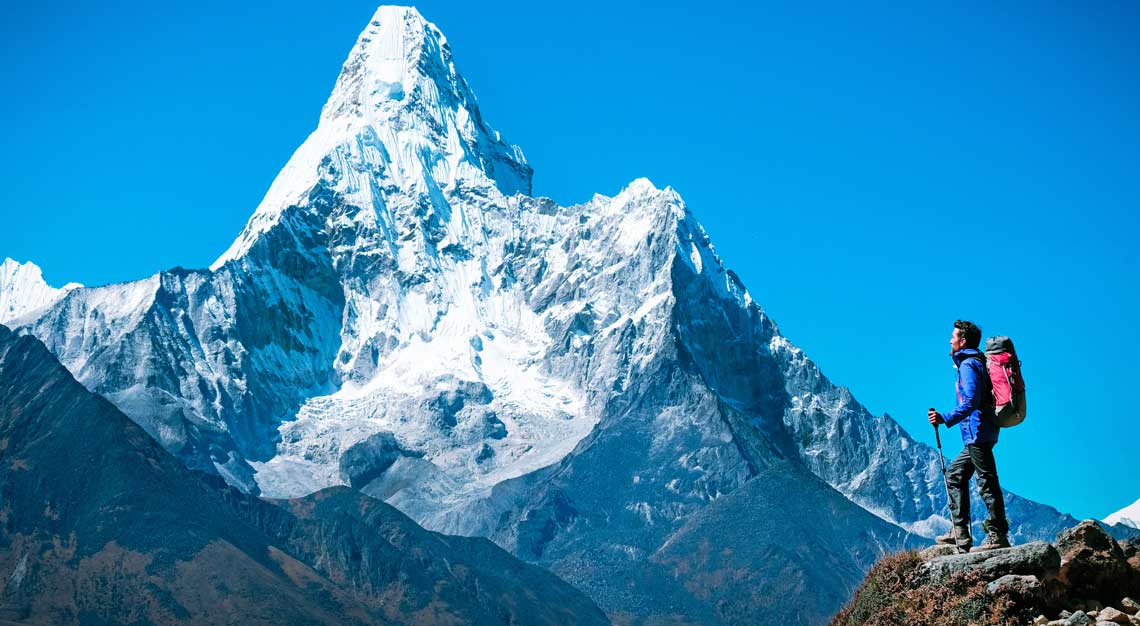

For some of us, relaxation means leaping off cliffs, rowing the Atlantic solo or summiting Everest, pushing mind and body to the breaking point – and beyond. So what do these overachievers have to prove? And to whom?

Lisa Thompson, a 48-year-old mountain climbing enthusiast, is recalling her harrowing trek on Bottleneck, one of the most perilous passes of her 8,611m ascent to the summit of K2 in 2018.

“This giant tower of ice is hanging above you, with chunks that periodically fall,” she says, “and you have to climb underneath it for hours.” But the biggest threat lay beneath. “You walk very delicately, right up against it, on a boot path that’s less than the width of your foot. And if you fall there, it’s something like a two and-a-half-mile (four-kilometre) drop.”

The Bottleneck comes about 8,230m into one of the world’s most treacherous climbs. The inherent difficulty of breathing at that altitude and the unsettling narrowness of the path aside, Thompson says the physical challenge is relatively minor for a seasoned climber. It’s the magnitude of being mere centimetres from plummeting over the edge and into oblivion that can be mindblowing. “Getting your body to move quickly and efficiently in a spot like that is 100 per cent mental,” she says. “It’s about just telling yourself you can do it.”

The death-defying feats of mountain climbing and other extreme sports tend to garner the lion’s share of attention, whether in highlight reels, Instagram feeds or action movies, but as in Thompson’s case, the mind can be the toughest obstacle to overcome. It takes a rare breed of human to voluntarily cling to the side of a mountain while hurricane force winds blow and temperatures plunge as low as – 32 degrees Celsius. Even an Ironman sounds like a stroll in the park by comparison. But rather than giving prospective athletes pause, that mental challenge is responsible for luring untold numbers of otherwise sane, accomplished professionals to take up pursuits that by definition put them in mortal danger. The profiles of high octane adrenaline seekers range from perfectionists and people trying to tune out the demands of their successful careers to those searching for a way to overcome grief. Their motivation is also typically a complicated mix of escapism, ego and achievement.

For Type A overachievers, pushing beyond personal limits to notch another victory is an addictive dopamine fix. The neurotransmitter is known for playing a role in how we feel pleasure, but it also helps activate human motivation. “When you get that dopamine hit, it makes you more motivated to reach for bigger goals in the future,” says Judy Ho, a clinical neuropsychologist based in California.

According to a recent poll by Heli, a company that curates adventure-travel excursions, 70 per cent of its clients work in finance, technology, entrepreneurship or start-ups, all known for their highintensity cultures. It’s a number that rings true to Jeremy Lindblad, the global director of business development and innovation at Lindblad Expeditions. “I see this a lot with our clients,” says Lindblad, whose company operates 15 ultra-high-end ships that carry travellers to far-flung destinations such as Antarctica for excursions like a subzero kayak ride among the icebergs, or Alaska to go rafting on the Chilkat River – trips that can cost US$38,000 (S$51,674) per person for two weeks. “They feel like, ‘I’ve won at a lot of things, and I want to do something that is challenging and introspective, and see where my body can take me’. They do one thing, and then they definitely have to do the next and the next. It’s an addiction, right? Instead of buying companies, they’re now summiting mountains.”

In Andrew Vigneault’s case, he’s doing both. When the 30-year-old technology investor and entrepreneur, who divides his time between New York City, San Francisco and Salt Lake City, isn’t busy making deals, he’s out kitesurfing in Aruba and Colombia or air-skiing off 1,829m peaks in Alaska. Vigneault and his group of mostly guy friends have used Heli to plan some of their adventures, and he says the directive to their guide is always “make us scared”. That means skiing off a 15m cliff and then landing to ski down another 457m vertical feet in deep powder through trees. Currently, he and his friends have a bet running: whoever does the first backflip off a cliff wins US$10,000 (S$13,577). They’re hoping to reach the level of Big Mountain professional skiers – Olympian Shaun White was an early idol. On their to-do list is conquering speedriding, a sport that combines their two passions of skiing and kitesurfing. “It’s like a drug,” says Vigneault. “If you want to feel the high, you have to keep pushing it.”

So far, Vigneault and his friends’ relentless press to achieve bigger thrills has resulted in only a few broken fingers. But the dangers are undeniable. On her climb up K2, Thompson witnessed a climber fall to his death because of a faulty rope. And, in March, Czech billionaire Petr Kellner and four others were killed on a heli-skiing expedition in Alaska when their helicopter crashed. Still, for some, the adrenaline fix is worth staring the grim reaper in the face. The quest for a biochemical pay-off is not a foreign concept in Vigneault’s career, either. Big-money deals are rooted in risk and rush. Could you crash? Sure, but as Vigneault puts it: “You get used to it. You sleep with it.” When he first started investing, he admits, the uncertainty was a struggle, but perseverance and wins overcame the pain of the pursuit. “Now a US$5 million investment doesn’t get me out of bed in the morning,” says Vigneault. “It has to be US$10 million (S$13.58 million) or US$50 million (S$67.88 million). It’s about how can I continue to level up?”

Plenty of athletes turn to extreme sports for good old-fashioned bragging rights. “For me, it’s about the symbol of climbing the highest mountain in the world, which is very motivating,” says Thompson. “With mountains like K2, so few people have done it. It’s a unique distinction.” Sometimes, though, it’s not only the rest of the world they want to impress, but themselves. Thompson, a Washington State resident who works in management for a medical-device company, had completed eight hard climbs, including Denali, before being diagnosed with breast cancer and undergoing a double mastectomy at age 43. Feeling vulnerable, she decided the best way to regain confidence in her body was to take her climbing to the next level, so to speak. She soon took on Everest, followed by Tharke Khang in 2017 and then the treacherous K2. “There was this strong desire to prove myself, especially after having cancer. I wanted to prove that I was still strong.”

Like a health scare, personal tragedy can act as a catalyst. Hard-core training and expeditions offer distraction from real-world problems. After the death of her 34-year-old brother eight years ago, which followed the deaths of two other brothers and her mother over the years, 39-year-old Cheyenne Quinn, who handles outreach and partnerships at mental health start-up, Happy the App, began to up the ante on adventure. Why would she risk her life after having seen so many loved ones lose theirs prematurely? It may sound counterintuitive, but according to Quinn, adventure brings a stillness to the chaos of the mind. “[These adventures] give me a brief period from my thoughts, which are constantly swirling,” she says. “My brain goes into more of an animal, or reptilian, state, and that’s very pleasurable for me.”

This focused, almost frozen, frame of mind is something high-performance athletes tap into frequently, and in her case, it was a saving grace. While she has pursued everything from kitesurfing in Sri Lanka to climbing Mexico’s 5,230m Iztaccíhuatl, the first time she just barely escaped death was in the lead-up to a drift-diving expedition (a riskier version of scuba diving, in which the diver is transported by the tide or current) in Costa Rica. About 12m below sea level, Quinn says, she and her guide were hit by a current so powerful that it knocked her mask off. With one hand gripping the anchor line so as not to be swept away, she had only one hand free to try to clear her mask of water.

A quick ascent to safety at those depths could cause decompression sickness, and her oxygen was already beginning to deplete as her breath quickened in the respirator. The key was not to inhale through her exposed nose, which is trickier than one might think, particularly in a highstress situation. “Through yoga, I had practised not to panic and for your body to understand almost immediately what the ramifications of freaking out would be,” says Quinn. As a result, she was able to find the calm in the current to clear her mask and even resume her descent to the anchor, after which, she says, the sensation of drifting with the current was like “floating in space”. Her oxygen nearly expended, Quinn still managed to keep her cool while ascending with the necessary safety stops.

Psychologists recognise the eerily tranquil sensation that Quinn and Thompson describe, referring to it as flow, a cognitive state of hyperfocus in which the mind zeroes in on a particular task or activity. According to Steven Kotler, the author of The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance and the founder and executive director of the Flow Research Collective, extreme athletes experience as much fear undertaking their treacherous escapades as would the guy who normally safely tees up at the country club. The difference is that hard-core athletes possess an uncanny ability to fight it off and attain a heightened flow state: they effectively use the terror to maintain focus.

“Your amygdala becomes a lot less reactive. It’s one of the foundational things that happens in the state,” says Kotler. “We get more courageous, but flow also follows focus. Whether you’re talking about Navy Seals, top athletes or CEOs, you’ll hear the same thing, which is that at the front end of any extreme thing, there’s always a spike in fear. That’s actually a good thing, because there’s mounting evidence you may have to trigger the fight response before getting into flow.” In other words, it’s our built-in mechanism designed to protect those facing risk, but some are better at channelling it than others.

Still, Kotler says, everyone is capable of tapping into flow, but those who actively camp on the doorstep of death have cracked the code. “Peak performance is about getting our biology to work for us rather than against us,” he says. “All of these people have figured out how to do that.”

Achieving a Herculean-level of concentration also seems to come more easily to those who, more often than not, are supremely self-confident. “All successful people I know have a healthy dose of narcissism,” says Ho. “And it could be argued there are multiple people who could probably be successful, but because they don’t think of themselves that way, they don’t even try.”

The same kind of ego that can override fear feeds off the glory of regaling friends with stories of harrowing rough-and-tough adventures. Deep in the wilderness of Canada’s Yukon, about as far north as you can go, Thierry Collot and his friends found themselves well out of their depth on the Macmillan River. But despite barely missing a plunge into a 2.4km-deep canyon, losing much of their equipment and coming face-to-face with 771kg grizzly bears, nothing could persuade Collot, the 58-year-old North American brand director of Zenith watches, and his crew to push their red panic button for an emergency rescue on their annual kayaking expedition.

They were used to doing excursions by water, whether in the murky climate of the Florida Everglades or among Newfoundland’s 200,000-ton icebergs. But the Macmillan, with rapids rushing 16km to 24km per hour over rocky terrain, proved their match. They had covered 64km midway through the fourth day of a 10-day trip, including hiking to their launch with kayaks in hand and navigating the waters. They still had 483km of river to conquer, but when one member of the group capsized his kayak and was nearly swept over a canyon cliff, they decided it was time to call it quits.

“I said enough is enough,” says Collot. “To make that decision against the testosterone-loaded group of friends I have was a big decision. That’s the dynamic of us four guys travelling together.” With no mobile phone coverage, they trekked through forest and marsh swamps and over a deserted old mining road for the next five days, navigating with just a compass and a piece of paper. They finally made it back to civilisation with the bragging rights of never hitting the panic button for rescue – and with one hell of a narrative to tell their friends.

Survival stories always make for compelling dinner conversation, books and television, but sometimes the fleeting nature of one’s life is the very reason athletes take on high-risk challenges in the first place. On 12 December 2020, at age 70, Frank Rothwell, a British entrepreneur who made his fortune manufacturing portable buildings, set out to row 4,828km across the Atlantic solo. Rothwell traversed the ocean in a seven-metre-long rowboat weighing 454kg. He completed the journey, which raised US$1.6 million (S$2.17 million) for Alzheimer’s research, in 56 days, finishing on 6 February 2021, a week ahead of schedule. It had taken a year and a half of planning and training, and cost about US$167,000 (S$226,703) of his own money. He ate nothing but freeze-dried Pot Noodles, using heated, filtered seawater, and was exposed to the elements the entire time, save for sleeping in a small cabin just big enough for his body and his gear. He put the boat on Auto-Helm steering at night.

But if you think that’s borderline insanity, it’s just par for the course for Rothwell. He sailed around the world at age 52, five years later became only the 10th person in the world to circumnavigate North and South America and, at 66, was the oldest contestant to star on British adventurer and TV personality Bear Grylls’ survival show, The Island With Bear Grylls (beating 79,000 other applicants for a spot). Prior to his casting, he had never heard of the reality-style competition. “I spent five weeks on this island, and they just put you out there with two buckets and two axes, and away you go,” says Rothwell. He built a canoe from scratch, macheted the head off a snake and generally outperformed the younger contestants. “They didn’t show me building the canoe,” says Rothwell. “The advertisers didn’t like the idea of an old man showing the young people how to do it.”

Speaking after his Atlantic crossing, he tells Robb Report he has no intention of slowing down. Just last year Rothwell went heli-skiing in Canada. “My father said to never let anybody tell me I’m too old,” he says. “I’m trying to encourage people to not just have a bucket list of things they want to do, but to actually do those things. Have a go.”

Ultimately what it comes down to is incremental training. The seemingly impossible never happens overnight. Extraordinary athletes, Kotler says, “are just pushing a little harder over extended periods of time. They understand that being uncomfortable is part of any great achievement.” And sometimes you may have to risk your life to get there.

This story first appeared in the August 2021 issue. Purchase it as a hard or digital copy, or consider subscribing to us here