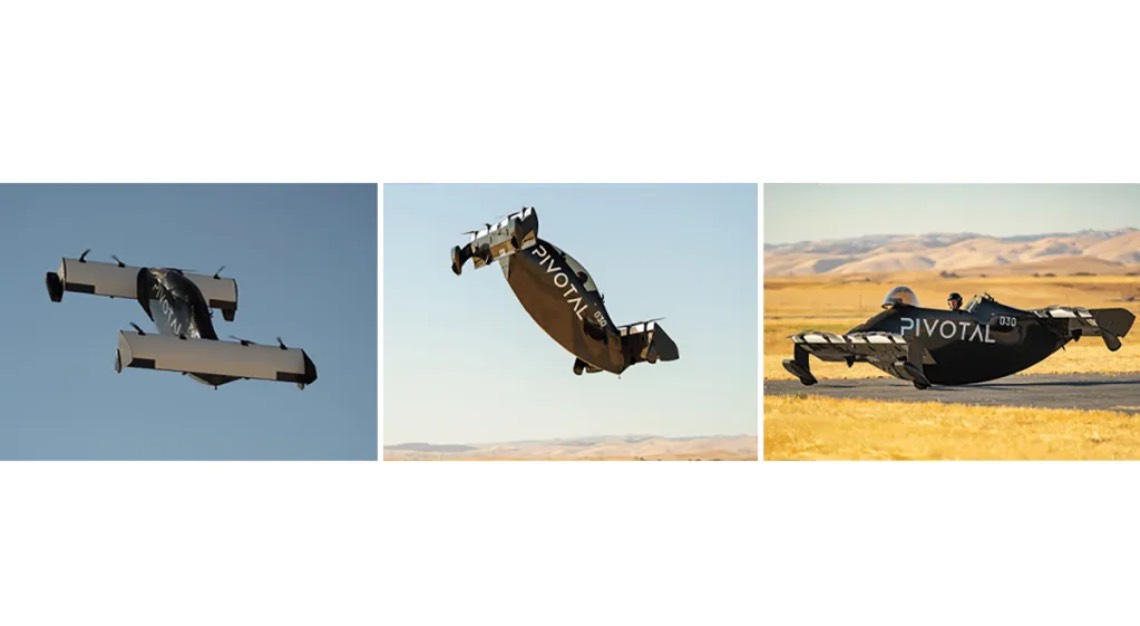

Pivotal’s BlackFly ultralight eVTOL is part of a growing new segment in recreational flying—one that doesn’t require a pilot’s license to fly. Aviation editor Michael Verdon went to California for a spin

Soaring some 60 metres off the ground, alone in a small aircraft with no piloting experience, sounds like a nightmare to some. But to me, flying solo has been a fantasy since a young Tom Cruise conquered the skies in an F-14.

Pivotal, and a half-dozen competitors in the emerging eVTOL space, have created one-seat, electric aircraft to release your inner Maverick, with no formal flight training.

But the Silicon Valley company’s 10-day programme for owners, pilot or not, is a mandatory part of the purchase agreement. It involves about 40 hours of flight training in a simulator, basically so you can prove you know the one-person aircraft well enough to fly it. That’s followed by 10 real flights.

The BlackFly (pre-production version of the Helix that I trained in and flew) has been around for 14 years, though it’s a much different aircraft than the garage-built plane Marcus Leng first flew in 2011 to prove an affordable, everyman electric plane could change the face of aviation.

At a summer barbecue, the Canadian inventor strapped himself into a 4.3-metre-long, two-wing oval contraption, telling guests they might want to stand behind their cars. He throttled up the electric engines and took off, careening wildly three metres above the yard, wingtips taking divots out of the grass. But the odd-duck aircraft stayed aloft, proving the concept.

Leng forged ahead. Four iterations, 7,000 piloted flights and 40,000 flight miles later, the BlackFly has transitioned to the production-ready Helix, with a US$190,000 base price, similar to a Lamborghini Huracan—though the Lambo can’t fly over remote terrain or cross lakes at 91.5 metres.

Pivotal, backed by Google co-founder Larry Page, moved from Toronto to Silicon Valley in 2014 to take advantage of the world’s largest brain trust of EV and battery tech. The Palo Alto headquarters includes two non-descript buildings that look like everything else in the neighborhood. But just inside the front door is where the pre-flight magic happens—an air-conditioned simulator room where I’d spend the next six days. In the production facility behind, a half-dozen Helixes are in various stages of production.

The BlackFly was designed for the FAA’s Part 103 Ultralight category, which requires no formal flight training, but stipulates a maximum dry weight of 115 kg (the BlackFly’s ballistic parachute and flotation bring total weight to 158 kg.), and pilots can’t exceed 100 kg. Ultralights are restricted to a top speed of 55 knots (102 km/hr), and flying over populated areas is strictly forbidden.

“At first, it’ll feel like you’re drinking from a firehose,” said trainer John Gilbert, joined by Sabrina Alesna, who led me through the 10-day training. Both are FAA-certified flight instructors who have taught many first-time pilots on other aircraft types.

Gilbert was right. I was a hot mess. I’m not a gamer, so the joystick felt awkward and the VR goggles—which replicates the pilot’s view from the cockpit as they fly over a virtual airport, banking, yawing, and tilting backwards 90 degrees—left my stomach in knots for the first few days.

Playing good cop and bad, Gilbert was encouraging but never shied away from pointing out mistakes that could lead to accidents. Flights ended with “good job,” or just as likely, “Okay, let’s try it again,” after I doubled down on the wrong joystick button or landed the BlackFly far from the pad.

But as we moved through the curriculum, I developed finesse with the stick, the only flight control. Alesna pointed out maneuvering didn’t require a death grip or hard, stomach-lurching turns.

The 19 lessons drilled in basic takeoff protocols and hover/cruise transitions via repetition. Later lessons covered emergency engine failures and GPS blackouts. Gilbert also introduced challenging wind conditions to keep me on my toes. Every lesson had a final-exam flight requiring an altitude within 15 metres of the designated flight pattern and 15 degrees of the given heading.

Beyond the intuitive joystick, the BlackFly’s secret sauce is its fly-by-wire controls. Used on fighter jets and now eVTOLs, fly-by-wire, or unified flight controls, is the invisible co-pilot doing the grunt work—automatically compensating for wind shifts and attitude changes, while monitoring in microseconds wind, altitude and engine conditions that could impact the flight. Think of it as flying an aircraft, while an invisible hand constantly makes minute but critical adjustments.

“There’s a lot of technology in the back end,” says Greg Kerr, director of Product Marketing. A former Tesla engineer, who joined Pivotal in 2016 to develop the software that makes the BlackFly safe for newbie pilots, Kerr has been behind many modifications the craft has undergone in its last eight years.

“The aircraft is designed to operate in a simple, intuitive way, but it’s a layered and sophisticated platform,” says Kerr. “We developed triple redundancies with three flight controllers, and each has independent connections to the motors to mitigate possible failures.” Two engines could go out, he notes, but the flight computers compensate without impacting safety—a possibility I hoped wouldn’t go beyond the sim training.

After simulator graduation, we moved to the rural airport in Byron, about an hour inland from Palo Alto. For days, I’d been flying over a virtual replica of the airport, covering the same landscape that now stretched before me: straw-coloured hills with wind turbines, grazing cattle and the farm where I’d made virtual 100 turns.

I’d be lying if I said I slept well the night before. It’s one thing making a mistake in the flight simulator, peeling off the goggles and sipping a smoothie to discuss why I’d careened across the runway on landing. Quite another when you’re really at altitude. Gilbert would be able to see my cockpit instruments from the ground, and we’d be in communication via radio. But he couldn’t take over the BlackFly. If I screwed up, it was on me.

The aircraft’s oval shape, rectangular wings and eight propellers resemble a shuttle in an early Star Trek! episode. Its 4.3-metre length and the similar lengths of the wings seemed at odds with how light it was on the trailer as we prepped. I strapped on my helmet, screwed in the canopy, and went through the pre-flight checklist.

The first few flights were minute-long blurs, hover-mode patterns, where I literally blasted off at about 70 degrees, nothing but blue sky ahead, following the same pattern on landing. In the simulator, it didn’t seem strange to be vertical on your back at 90 degrees, looking over your shoulder to find the landing pad. In real life, it seemed kind of nuts.

I was afraid I’d forget everything I’d learned in training, but muscle memory kicked in and I flew the patterns successfully—which involved about a dozen manoeuvres at different altitudes and speeds—finessing the nose to the wind and pushing the automatic landing button about nine meters over the pad.

Besides being a godsend to any newbie, the BlackFly’s auto takeoff and landing are critical features since it has no landing gear. The aircraft takes off from its curved centre keel, landing the same way. The jolt of power on takeoff was jarring, but thanks to the simulator, I was ready for it—though the loud whining engines in hover mode were a surprise.

The test flights got longer and more complicated, switching from hover mode (think helicopter) to cruise (regular airplane), flying the 1.6km-long circuit in the field next to the airport. On the first few circuits, my eyes stayed glued to the instrument panel, watching for red or purple warnings, occasionally scanning the sky for other aircraft. At one point I descended six metres to correct altitude and two engines stuttered, like they might stall. But it was the fly-by-wire adjusting prop speeds for descent.

The stats seem tame compared to other aircraft: I maintained a 76-metre altitude (the BlackFly has a ceiling of 1,402 metres) at about 80.5 km/hr. But as one of my fellow editors remarked later, “You could still die if you crashed.” Still, the limited range (20 minutes/32 kilometres), slow speeds and low altitude give plenty of time to adjust for mistakes—and enjoy the view.

“Any higher than that, it looks like Google Earth,” adds Tim Lum, who bought the first BlackFly about a year ago and has since done 450 flights, mostly over a 64-kilometre wooded valley beside his home in rural Washington. Lum has a practical, hype-less assessment of his one-seater (50 cents to recharge and ability to take off from his driveway) while pooh-poohing my main objection to ownership—that most people wouldn’t have the space to fly it. “I’ve set up four charging stations in my valley, so I can do five flights by lunch,” he says. “And once people in other parts of the area found out I was here, they’ve invited me to fly over their land. It’s definitely do-able.”

By the fifth flight, I was getting into the fun factor—the whole point, really. The BlackFly knew what it was doing, I realised, so I took time to appreciate the beautiful landscape, the cows grazing, the real man sitting on the porch where I’d made so many simulator turns. Since I had good battery reserves, I did an extra lap on that last flight to string out the experience, then came in for a final landing—30.5. metres too high, but the fly-by-wire compensated and brought me down.

The aircraft is all-carbon-fiber composite, with aluminum and titanium reinforcements. The exterior looks cool, but the interior is barebones, with a hard seat and iPad bolted to the console. The Helix has higher-quality fit and finish, with landing cameras, beacon lights, ADS-B transponder, and on the more expensive models, advanced chargers and custom finishes.

Would I buy one? Maybe, if I had the land and funds. I was impressed with the professionalism and enthusiasm at Pivotal about bringing the Helix to the masses—for now, the well-heeled masses—and eventually to EMS and firefighting. Everybody from Gilbert and Alesna to the engineers and production team I met were excited to be part of the project.

Perhaps most impressive was the fact that they didn’t rush to market. It took 10 years and many thousands of hours to develop the BlackFly. Pivotal kept the project secret until 2018, when they were finally sure it would go to market. I’d come half-expecting a dozen guys in a garage, but this was a 200-employee facility, moving from startup to production.

The ultimate litmus test of any experience is whether you’d repeat it. Going into the training felt like it would be a one-and-done. But two days later, I caught myself thinking how great it would be to go up again. It felt like I was just getting started.

This story was first published on Robb Report USA