With the goal of sharing the genetic wonders—and matter—of top athletes with the rest of us, scientists are making cutting-edge advancements

You’ve seen the headlines. Things like, the seven habits of people who never get sick and the 10 things this 100-year-old triathlete does every morning. Whether you’re scrolling on Instagram or catching up on the news, optimal-health clickbait has become a genre that’s impossible to avoid. Inevitably, there is some practical advice mixed with a wacky tidbit or two, along with shoppable links to supplements or fitness routines. So you make a mental note to remember one of the more resonant tips and move on with your day. But what if, rather than reading about the habits of highly effective and healthy super humans on the Internet, you had something more to gain from them? Like their DNA.

From probiotics to cosmetic treatments to, yes, faecal transplants, using the material wisdom of those fitter, stronger and sharper than you now can mean taking on not just their early bedtimes and consistent workouts but also their genetic material. Researchers on the cutting edge are increasingly focused on studying the planet’s healthiest inhabitants and applying their freakishly robust make-up to the rest of us. Darwin would be proud.

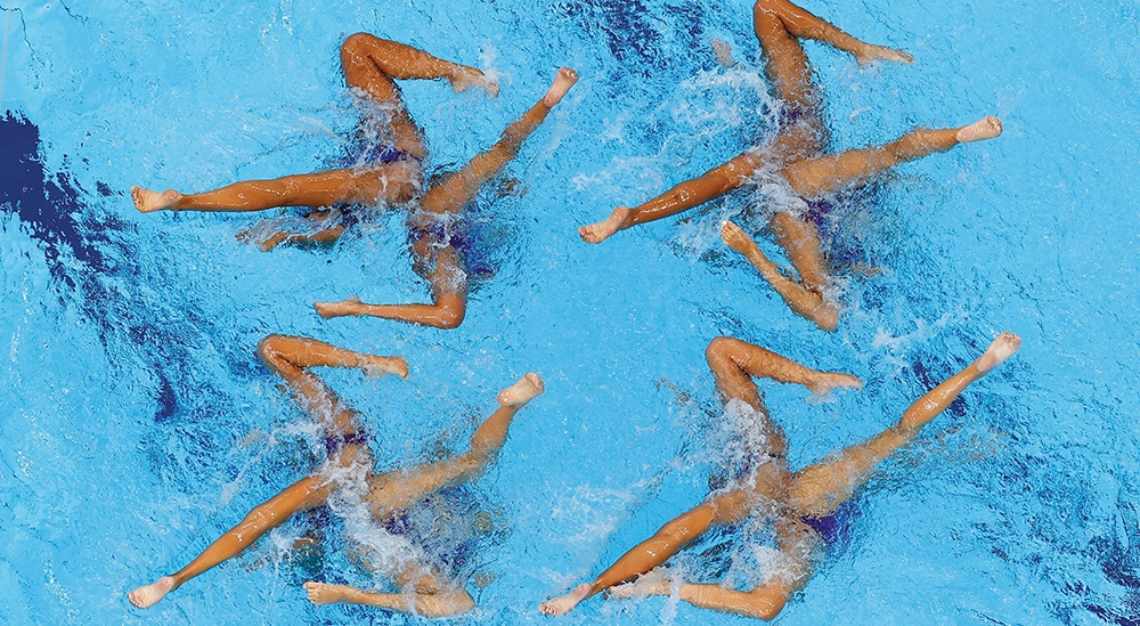

“If you look at biomedicine, the notion is to look at unhealthy populations and what doesn’t work and how we can correct it to promote health,” says Jonathan Scheiman, Ph.D., co-founder and chief executive officer of FitBiomics, which is trying to take the opposite approach, beginning with understanding the microbiomes of so-called “super performers” who represent the peak of health and fitness. The company was born from intellectual property at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard. George Church, Ph.D., who leads synthetic biology at Wyss, is also a co-founder. Scheiman, a former college basketball player whom a colleague calls “the Tony Stark of probiotics,” studies what makes the gut microbiomes of Olympians and other world-class athletes unique and translates that information into something he says anyone could benefit from. But the lab work is not just for the sake of data: FitBiomics debuted Nella, a probiotic supplement for gut and digestive health, last year. It contains three proprietary bacterial strains derived from… elite-athlete poop.

“Our gut microbiome influences pretty much everything we do, from a functionality and health perspective,” Scheiman says. “It breaks down the foods we eat and digests them into nutrients that our body can absorb. It synthesises neurotransmitters to affect functionality, which has an impact on sleep, and it interacts with our immune system to support recovery and suppress inflammation.” His theory is that most probiotics currently on the market are decades old and traditionally derived from baby stool, animals or food; the ones he’s using, by contrast, are associated with greater health by virtue of the fact that they come from these athletes, a “natural-selection process” he says we can all benefit from thanks to the correlation with their physiology. The Nella supplement was beta-tested on 257 participants who consumed it daily for two weeks and reported their results using online surveys. An impressive 94 per cent saw a boost in at least one category. Improved sleep quality was the top benefit, with 45.1 per cent, and decreased fatigue frequency, less soreness after workouts and more regular bowel movements each scored above 30 per cent. There has not been any testing to show how it performs against existing probiotics, but a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial with 10 members of a professional soccer club is close to completion.

Five-time Olympic gold medalist swimmer Nathan Adrian, six-time world champion wrestler Adeline Gray and ultramarathon runner Kyle Pietari are among the athletes sharing their faecal matter for the benefit of humanity. The bacterial strains are isolated, purified and then replicated via fermentation—and beyond the point of identification, so you don’t know exactly who donated the probiotic you’re ingesting, but the idea is that their optimal condition will literally rub off on you. Despite the transient nature of probiotics, which tend to pass through the gastrointestinal tract within 24 to 72 hours, Scheiman says they could still have a tremendous impact on functionality. “They could help us digest food, they could help us metabolise lactic acid, they could interact with our immune system, they could produce neurotransmitters,” he says. “There’s a lot they can do.” The downsides are similar to other probiotics: a possible adjustment period of three to four days with mild gas, bloating or more frequent trips to the bathroom, all of which should subside within a week or two.

The next FitBiomics product, Veillonella, which has recently passed necessary safety studies, works in an entirely different way. It contains another novel bacterial strain that grows in abundance in the microbiomes of super performers. “We found a similar pattern in how this bacteria, which eats lactic acid, increased in the gut after strenuous exercise,” says Scheiman. Because lactic acid is a byproduct of exercise that is linked with fatigue, the discovery became “a light-bulb moment, an opportunity to have an organism that could convert a byproduct of exercise into something to promote endurance.” Pre-clinical data, published in the journal Nature Medicine, showed the identification of a “performance-enhancing microbe” found in the guts of Boston Marathon runners, ultramarathon runners and Olympic-trial rowers.

The athletes involved in FitBiomics receive their data and are compensated with shares in the company. “We view them as leaders of the new school,” Scheiman says.

“Through [letting us understand] their biology and their health, they’re helping us change health for everyone.”

Billionaire philanthropists Clara Wu Tsai and Joe Tsai are not just casual observers of peak human condition. As the owners of the NBA Brooklyn Nets, the WNBA New York Liberty and the pro lacrosse team San Diego Seals, they are surrounded by high performers, and now they want to tap into that magic for the benefit of varsity track stars, weekend warriors and those who don’t exercise at all. They created the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance with a plan to invest US$220 million (S$303 million) over 10 years in six institutions, including the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and the University of Oregon, to understand what aspects of our brains and bodies determine peak human performance. The goal is to study superior specimens to improve the health of a global population.

“Being athletic and understanding the value of athletics on human performance is something that we value as a family,” Wu Tsai said in a filmed announcement before the Tokyo Olympics last summer. “What has really surprised me is the lack of advancements in the areas of healing and training regimens, largely due to underfunding in this space.” In addition to focusing on elite athletes of all genders, the alliance’s discoveries will be freely available and likely be used by other scientists in their own research and innovations. One of the “moonshot” projects on the Wu Tsai slate is the creation of a “Digital Athlete” at Stanford University that will use artificial intelligence and medical imaging to determine how to extend peak performance for all—knowledge that could apply to an athlete in training or an elderly individual seeking to live independently longer.

Young athletes hold an obvious appeal, but some researchers are turning to a more unexpected, though no less remarkable, cohort: the old and vigorous. Rudolph Tanzi, Ph.D., an actual rock star scientist and Harvard professor of neurology who has discovered several genes that contribute to Alzheimer’s and plays keyboards for Aerosmith’s studio albums, says that in order for doctors to responsibly prescribe something new, they have to understand what really contributes to a healthy body, including one of our least understood organs: the brain.

His work as the co-director of the McCance Center for Brain Health at Harvard’s Massachusetts General Hospital homes in on what makes a vibrant brain. “Rather than only look for biomarkers of disease or waiting for people to get sick with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, at which point the brain has already deteriorated to the point of dysfunction and you’re trying to turn back the clock, we’re asking, ‘How can we know whether our brain is healthy?’” He points out that we can easily check the health of our heart, our pancreas, our blood pressure but “there’s no checkup for your neck up. The doctor looks in your mouth, your nose—looks in the holes—and that’s it.”

The centre is currently researching how genes are expressed and how our bodies metabolise, as well as the gut microbiome, to understand impacts on the brain, what’s special about healthy people and how those lessons could translate to greater populations. “Until you do that work,” Tanzi says, “you’re guessing.”

There are, indeed, many biohacking brands that are built off at-home nasal swabs, faecal samples and spit tests, each with the promise of recommending skincare, supplements, fitness routines and diets based on your individual constitution. Tanzi’s advice is to take those promises with a large grain of salt. “The hard work is just being done now,” he says. “I know because I read the literature. People might say, ‘I have a new idea for a company: We’re going to take your blood, we’re going to look at this, this, this, and we’re going to sell you these supplements—and we’re not going to tell you that we say the same thing to everybody.’ That’s skeptical, but it can get that bad.”

Tanzi’s goal is to reliably recommend a protocol that can enhance how our brain ages. His lab at Mass General created an “Alzheimer’s in a dish” model, developed in part because he is vegetarian and wanted to avoid testing on mice. It enables sophisticated testing for every approved drug and supplement on the market to determine which ones can prevent or treat the disease. He is also currently studying the oldest living “super agers” in a collaboration with Boston University. The work focuses on centenarians who are as cognitively sharp past 100 years old as they were at 60 to understand what’s special about their DNA and epigenetics.

“I’m trying to take the visionary stuff,” Tanzi notes, “and say, ‘How do we get there?’”

It’s possible that borrowing from our younger counterparts is one path. Research published in the influential journal Nature in May demonstrated that old mice given an infusion of cerebrospinal fluid from young mice for one week had improved cognition, not just for remembering the past but also for creating new memories. Human application is far off, and similar studies using blood have shown cognitive improvements as well but have yet to be widely and successfully applied outside the lab, despite Lance Armstrong admitting on Oprah that he received blood transfusions to boost his oxygen levels in between multi-day bicycle races. Silicon Valley has long been seduced by the promise of immortality, and young blood seems a direct way to get there. But start-ups such as the California-based Ambrosia, which reportedly charged people US$8,000 (S$11,050) to participate in a study and receive a litre of youthful plasma, have been hindered by FDA warnings, shut-downs and quiet re-openings. The FDA has cited health risks combined with little evidence to bear out lofty claims.

One thing that’s already been put into action is React Neuro, an advanced eye- and voice-scanning virtual-reality device that was developed in part to help track athletes’ brains before and after injury, clocking nano movements in a far more precise, quantifiable way than having a patient follow a doctor’s finger after a blow to the head. Tanzi, who is a co-founder of the company, hopes that the invention could become a “blood-pressure cuff for the brain,” perhaps a regular part of a physical exam of the future. He has used the device with the New England Patriots and the Boston Celtics and in senior-living centres to measure progress and understand changes over time, assessing what has happened to an athlete after a season playing in a professional league or a septuagenarian who’s had a life-altering event, such as a stroke.

Anesthesiologist Abhinav Gautam, M.D., and health-care investor Christian Seale are pioneering a currently available procedure for pain management that treats an organ that was discovered only four years ago, even though it makes up 20 per cent of our bodies. In 2018, researchers at New York University published findings on the interstitium, a fluid highway that lives between our skin and our muscles and transports nutrients, ions and proteins from head to toe. Seale posits that part of the reason it was less observed by Western-medicine doctors is that they typically train on dead bodies, and this layer “pretty much evaporates as soon as one passes away.” The lack of understanding about the interstitium has made it an understudied area with few direct treatment options. But Gautam developed the procedure entirely on active bodies. “We know it’s very innervated, which means it has a lot of nerve endings,” says Seale, who adds that this won’t be news to practitioners of ancient traditions that have targeted the interstitium for centuries, even if they don’t use that name. “If you look at Eastern medicine and Chinese Ayurveda, this is where the chi flows, where the chakras are, or the meridians.”

Gautam, a former competitive tennis player whose interest in pain relief stems from attempts to fix his faulty shoulder, and Seale started the company Vitruvia to offer Relief, a minimally invasive ultrasound-guided procedure that uses needles to break up scar tissue and free nerve before rehydrating the treated area (common targets are shoulders, knees and hips). Seale compares a pained area to a river punctuated with rocks that change or block the flow of water. The Relief procedure, he says, removes the rocks and redirects the water so it flows in a more fluid, organised fashion. So far, two-time American League MVP Miguel Cabrera, retired star slugger David Ortiz, tennis player Tommy Haas and actor Danny Glover have received the treatment, and the protocol is now expanding to professional athletes and top performers in Miami and Los Angeles.

At the cosmetic level, several European skin-care brands, notably Neocutis, have tapped into even younger specimens, drawing from human and sheep foetal tissue to create serums and creams designed to regenerate skin the way a baby heals quickly after getting a cut or bruise. But these days, it’s more likely that products are plant-based, even if the processes they induce are similar. Cult French skin-care brand Biologique Recherche makes Crème Masque Vernix, which the company describes as a “biocopy” of the protective composition of vernix caseosa, the white substance that coats newborns as they exit the womb. Like the real thing, the cream consists of water, lipids and proteins to combat dryness and regenerate the epidermis.

But whether you are drawing from the newly born or the well-aged, there is a clear and under-explored value in grasping what makes a prime human specimen function well throughout all stages of life. Whether he’s looking at blood-based biomarkers or neuron activity, Tanzi says the goal is to be able to have our routine health guided by more of what makes us thrive. “I want to know the indicators, and then I want to have interventions that drive those up rather than just get sick and try to drive down the ones that are bad,” he says. “I don’t want to know what tells me I’m sick,” he adds. “I want to know what tells me I’m healthy.”

This story was first published on Robb Report USA