For starters, filling the 128-litre gas tank of the Mercedes 300SL costs a pretty penny

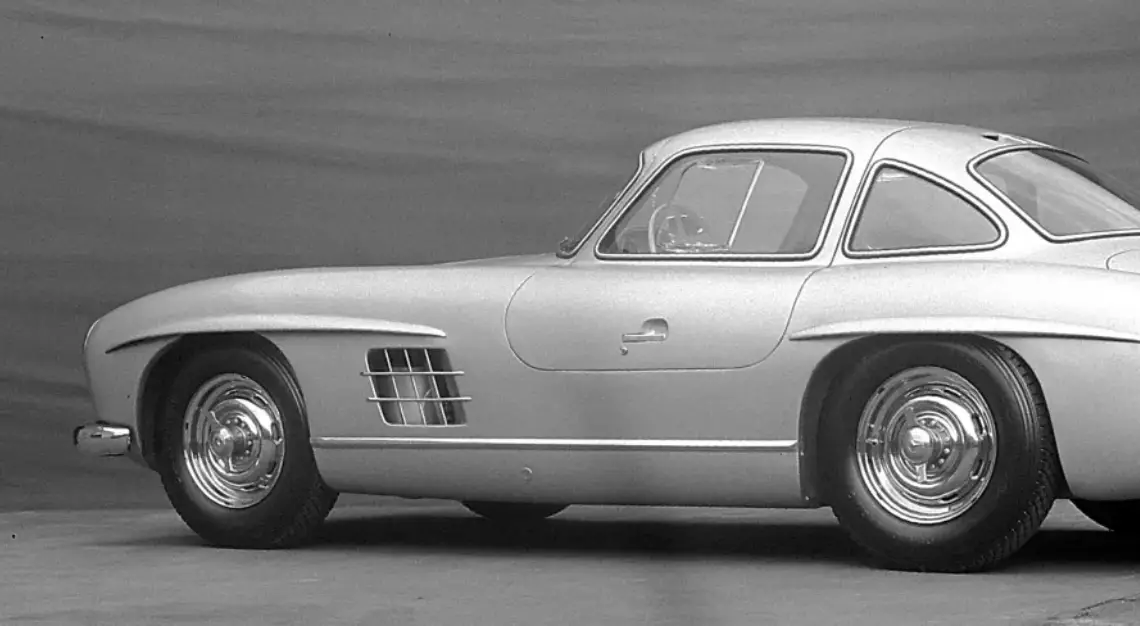

Flogging a 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300SL over 1,600 kilometres during Italy’s Mille Miglia is the most exhilarating driving experience, one where you get absurdly intimate with the world’s first supercar. And what a machine this is. It’ll rocket along at 193 kilometres an hour without a wiggle, deafen you with the 3.0-litre inline-six engine’s sonorous roar, and leave your palms flecked with sweat whenever you’re hammering the brakes—drum brakes aren’t the tidiest under heavy pressure.

The 300SL was the fastest production car when it debuted in 1954, the first to achieve 160 miles per hour. It’s still quite fast, the sensation of speed and danger heightened by a lack of anything safety-related, including seat belts. It’s also relatively comfortable. After several hundred miles of hard driving, you won’t emerge a shattered shell of a human, aching and cramped, barely able to stand. (Your back will be drenched, though. There’s no airflow in the cabin, even with the tiny valence windows cranked wide. Traveling at 160 kilometres an hour, a lit match will burn down to your fingertips.)

A lot of facts are known about the venerable Mercedes-Benz 300SL, but the eight facts that follow are largely gleaned by spending six days and 1,600 kilometres behind the wheel one of the best sports cars ever made.

It’s terrifyingly fast — but extremely collected

At 1,295 kilograms, the 300SL is not terribly heavy, compared to cars of its day. (The “SL” means super-leicht or super light.) The father of the 300SL, Rudolf Uhlenhaut, a German engineer with Mercedes since the 1930s, took a 49-kilogram steel tube frame chassis, affixed a steel body, aluminium doors, hood, dash, and trunk lid, and dropped in a 3.0-litre inline six mill from a 300 sedan. In this tune, it’s good for 215 horsepower and 273 nM of torque. It sounds paltry when measured against today’s super steeds, but it gets the 300SL absolutely hauling.

At 160 km/h, it’s so superbly stable, you can remove your hands from the wheel, and it doesn’t stray an inch. At 209 km/h, just when the autostrada hash marks start to blur into a solid line, it’s so sedate that you have to glance at the speedo to confirm that you’re indeed in the triple digits.

The engine comes alive at 4,000 RPMs

That’s around the mark in the revs where the exhaust becomes so tantalizing that you almost want to keep it there. But you must press on, to hear it crescendo into a bellowing roar around 6,500, filling the cabin with a rich, deep note that lingers in your brain for months and years.

There’s a passenger horn button

A small chrome button on the passenger’s side of the dash is a second horn. John Fitch, an American who piloted a Mercedes 300SL to a class victory in the 1955 Mille Miglia famously said, “I can’t contemplate being a passenger because they are always a pessimist. The driver is always an optimist.” Truth. When the driver’s occupied, going full tilt, the co-pilot can rail the button to alert pedestrians you’re about to barrel through.

Driving hard requires commitment and nerve

There’s a rear swing axle that abhors hesitation or lifting mid-corner. Set the axle by burying your foot at the start of the turn and God help you if anything hinders your advancement. The moment you lift—or worse, brake—the weight lifts, and you’re rewarded with snap oversteer. You also have to know about how much fuel is in your tank; that can affect how well the axle is setting.

It’s impossible to look cool during ingress and egress

I’m 1.88 metres tall and the available opening in the gullwing’s door isn’t big. Complicating matters, the tiller is the size of an extra large pizza—though it does tilt down during entrance and exit. Everyone looks absurd shimmying into the driver’s seat. First, sit on the door sill, then swivel your legs in, one at a time, then drop your butt into the plaid-upholstered seat. Nothing like driving a US$1.5 million factory-restored piece of automotive history, and clambering out while your phone goes flying.

Heel-toeing is a breeze

The 300SL’s four-speed manual transmission is decent and smooth. First gear is short, expiring quickly, but second and third are tall, so there’s plenty of time to get the engine wailing high. It takes a day to get the positioning of (my large) feet correct in the toe box, but once sorted, it’s easy to blip the throttle while braking, and slip into a lower gear. Fourth to third was less finicky than third to second, initially, but by the end of the Mille Miglia, all the movements were fluid.

Filling gas is wildly expensive

The upside of having a 128-litre tank: you can drive hard for hundreds of kilometres—the 300SL averages about 9.35 litres per kilometre. The downside: each fill-up is north of US$200, when you’re feeding it premium. (Skimp on the octane grade and be rewarded with engine knocking.)

The most expensive 300SLs are alloy-bodied

About 1,400 300SL gullwing coupes were made between 1954 and 1957. They cost US$6,800 in 1955 (US$77,000 in today’s dollars). Now, those hammer at auction around US$1.4 million. However, there were 29 fully aluminium-bodied variants, about 90 kilograms lighter than their steel brethren. These employ plexiglass in lieu of glass, an engine with 15 more horsepower, and alloy wheels. These are significantly pricier, fetching more than US$6.5 million at auction. The most expensive 300SL is the 1955 300SLR Uhlenhaut Coupe, an eight-cylinder beast raced by the likes of Stirling Moss. Two of these nine race chassis were converted to road cars, and one became the most expensive car ever to be sold at auction, commanding US$150 million in 2022.

This story first appeared on Robb Report USA