Filipino food is something you typically find in the comforts of one’s home, but the oft-underappreciated cuisine is now making waves in Manila’s burgeoning fine dining scene

At first, Filipino fine dining might seem like a paradox to many locals. They are brought up on the humble yet richly flavoured adobong baboy, or braised pork belly stew, marinated with whole peppercorns, bay leaves and vinegar. Or fried boneless bangus, the Filipino milk fish, which is sliced down the centre – head, eyes and all. The cut exposes the jellylike pewter-grey belly – the best part of the fish, by all accounts. The food is hearty, wholesome and sprawled on your dining table without a starched white cloth. Your corner of the table will inevitably be covered in stains, grains of rice and other signs of a convivial family meal. Today, there are restaurants the world over with “reimagined” Filipino cuisine, sourcing ingredients locally and using modern or Western cooking techniques.

According to the Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO) estimate, there are more than 10 million overseas Filipinos, around 10 per cent of the population, living permanently or temporarily in another country. So, when one thinks about the rise of Filipino cuisine – and that of Filipino fine dining – it should not come as such a surprise.

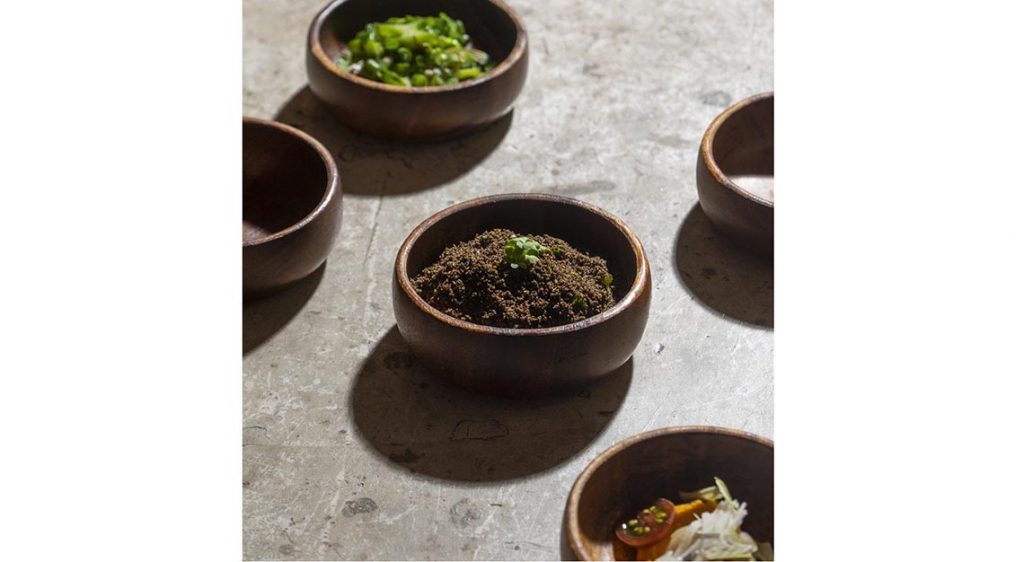

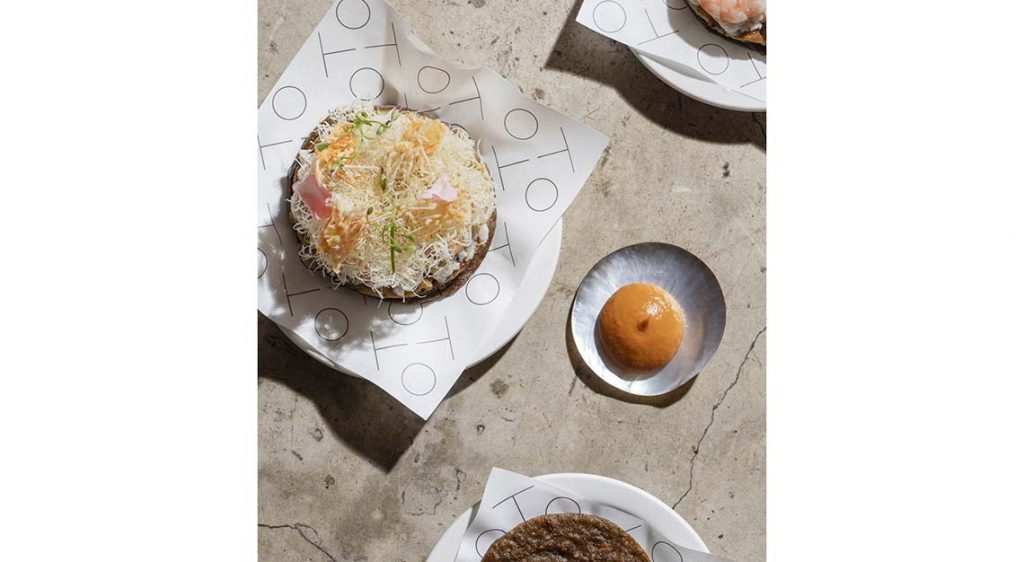

Toyo Eatery in Makati, Manila is run by chef-owner Jordy Navarra. The restaurant’s signature dish, Garden Vegetables, is inspired by the Filipino folk song Bahay Kubo about a garden with 18 different vegetables. Toyo, named after the Filipino word for soy sauce, also offers banana catsup on its menu. Navarra says, “Banana catsup, a local invention, is a condiment that’s so uniquely Filipino. The idea for our dish was to give this condiment its due credit. We make our banana catsup from fermented bananas and banana vinegar. It’s then served with Tortang Talong (aubergine omelette) with alternating layers of shrimp and crabmeat.”

Navarra, who trained under experienced overseas chefs, opened Toyo Eatery in 2016. The restaurant was awarded the Miele “One to Watch” Award for Asia in 2018, and signifies the growing popularity of Filipino cuisine. “A lot of people in the Philippines are fostering this bigger support for all things locally produced,” Navarra says. “This is seen in design, art, fashion, and even food.”

“I would like to think that Filipino cuisine being on the up-and-up has something to do with Filipino diners being more aware, and also being more outwardly supportive of what the country has to offer. That and diners in general are curious and open to trying things that might not have been on their radar before.”

Gallery by Chele, located in Taguig, Manila, is another modern fine-dining restaurant serving what it refers to as “essentialist cuisine”. Chef Jose Luis “Chele” Gonzalez and his culinary partner Carlos Villaflor use ingredients, techniques and traditions inspired by the Philippines. Gonzalez travels around the Philippines and Southeast Asia, uncovering common local ingredients and the traditional cooking methods of farmers, fishermen and home cooks.

Spanish-born Gonzalez takes practices that have been “lost to the modern world” and brings them into the beautifully designed 55-seater restaurant. Some might see this as some kind of cultural appropriation – adopting elements of a minority culture in a Western setting. But there is something respectful about the work at Gallery by Chele that permeates into the food, drink and interior design, and the fine dining setting no longer seems like a fussy Western concept.

Filipino industrial designer Kenneth Cobonpue, who is known for using natural and local materials, designed Gallery by Chele’s modern ergonomic furniture, and the result is an inviting look. The menu includes Ube Tacos, a violet yam often used in sweet dishes such as Halo Halo. Here, the chef uses the flavour to host octopus and local mushrooms. Tortang Takoyaki is a Japanese twist on the Filipino aubergine omelette. The tortang is rolled into takoyaki balls, with squid ink and pinakurat, a spiced natural coconut vinegar. Villaflor, who was mentored by Gonzalez, says, “I want Filipinos to be proud of their cuisine, and in the process, change how they eat.”

When it comes to Filipino fine dining, Toyo’s Navarra says, “Nowadays, fine dining doesn’t necessarily equate to being formal dining. It’s gone beyond the old world idea of white linen-covered tables and expensive outsourced ingredients. The formality isn’t non-existent, it’s just not required any more. A fine-dining experience doesn’t have to be fussy. It can just be about the food and the service.”

Filipino fine dining may be flourishing, but it hasn’t hit Singapore’s dining scene or the rest of Southeast Asia just yet. It’s a pity, because it would certainly fit right in with the various Michelin-star restaurants and global cuisines that currently call the red dot a second home.

This article was first published in Style by South China Morning Post.