Electrogenic’s conversion kit bolts in without any chassis modifications and can make the car quicker off the line than a new Carrera

Last summer, as Paul McCartney rocked the main stage at Glastonbury, a small fleet of Land Rovers was working silently in the surrounding fields. The classic 4x4s had been converted to battery power by Electrogenic, in a joint project with Worthy Farm—home of the UK’s most famous music festival.

After the final encore of Hey Jude had faded away, Electrogenic was inundated with enquiries about its Defender EV conversion kits: one aimed at farmers, the other for road use. Now, the Oxford-based company is applying this same “plug-and-play” approach to electrifying classic sports cars.

The first two cars chosen—the Jaguar XK-E and Porsche 911—aren’t so surprising, perhaps. However, while there’s nothing too controversial about swapping a clunky old Defender engine for a smooth and quiet electric motor, removing the flat-six from a 911 seems almost sacrilegious: like remixing “Love Me Do” with a pounding EDM bass line.

We’ll get to the emotive issues shortly, including what this Porsche is like to drive, but let’s examine the nuts and, well, volts of the conversion first. Suitable for any G-series 911 (built from 1974 through 1989) or 964 (from 1989 through 1994), the electric-conversion kit bolts in without any chassis modifications, so the process is fully reversible. Prices are set by the specialist doing the work—Electrogenic has a growing network of approved installers across the US–but anticipate spending around US$120,000, plus the cost of a donor car.

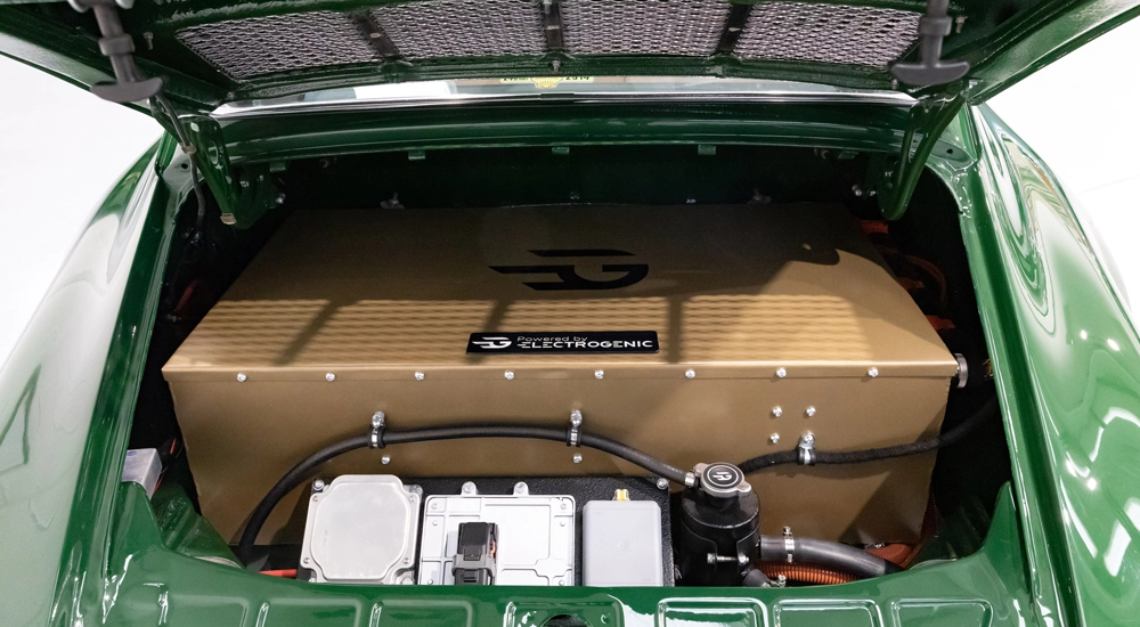

As with the Land Rover, there are two options available. The E62 kit (fitted here) teams a 62 kwh battery with a 160 kw motor: good for 220 hp and a zero-to-100 km/hr time of 4.9 seconds. The E62s package increases motor output to 240 kw, for 300 hp and the ability to propel the car from a standstill to 100 km/hr in just 3.8 seconds: quicker than a new 992 Carrera.

With both kit options, real-world range is between 290 km and 320 km, while a maximum charging speed of 50 kw allows a full fill-up in one hour using a public rapid charger. With a home wallbox, charging from empty takes up to 8 hours. And no, before you ask, these aren’t recycled Tesla components: all of Electrogenic’s EV hardware (and software) is custom to the company.

This particular car is a 1985 3.2 Carrera that has been “backdated” to resemble a 1973 Carrera 2.7 RS. With Irish Green paint—a period Porsche colour—dished Fuchs wheels and the trademark RS ducktail, it looks every inch the classic Neunelfer. Only a slightly raised ride height, to compensate for the extra 120 kilograms on board, hints at what lies beneath.

Aside from a re-trim in tasteful tan leather, this 911’s cabin also looks near-stock. Its five-dial display is still present and correct (and still obscured by the steering wheel), although the fuel gauge has been replaced by a battery-charge indicator. The obvious difference is the absence of a gear lever: replaced by a rotary switch to select neutral, drive, or reverse. Look closely and you’ll also spot two 400-volt electric heaters under the dashboard. They warm the interior almost instantly—quite unlike the HVAC system in an air-cooled 911.

This Porsche might be 10 per cent heavier than Stuttgart intended, but mounting two-thirds of the batteries in the front trunk, with the remainder (plus the electric motor) beneath the engine lid, actually makes it better balanced. “Weight distribution is 49 per cent at the front and 51 per cent at the rear [versus 40:60 in a stock 911], which gives you more stability and confidence,” says Electrogenic engineer Alexander Bavage. “We aim to build cars that are great to drive from an engineering point of view, rather than simply from a purist’s perspective.”

On the tightly coiled airfield circuit at Bicester Heritage, a former British military base, I can appreciate what he means. The 911 doesn’t squat on its haunches so readily when you apply the power, and it’s less willing to tip into oversteer. The electric drivetrain serves up instant torque, linear response, and a real shove-in-the-back turn of speed, but not such as to overwhelm the stock Carrera brakes and torsion-bar suspension. If you went for the 240 kw E62s motor, I suspect some upgrades would be in order.

Going fast and sideways in the electric Porsche is great fun. The vehicle blends the analogue and the digital in a way that most electric cars singularly fail to do. Yet something is missing, too. Without a flat-six behind the rear axle, there’s no high-rev howl, no visceral vibrations, no sense of mechanical connection. It feels more like a 911 simulator than the real thing.

I come at this from the perspective of a Porsche enthusiast, well versed in the classic 911 and its quirks, so it’s difficult to be objective. Judged in isolation, the Electrogenic revision of the 911 is an engaging sports car and a real talking point, with many notable advantages over the original: zero tailpipe emissions, improved refinement, low running costs, one-pedal driving, toll-free access to European city centres—perhaps a cleaner conscience, too.

It isn’t for me, but it might be for you. And besides, many customers will surely own a regular 911 as well. An Electrogenic E62 for weekdays and an old-school 911 for weekends? Now that’s a two-car garage I could live with.