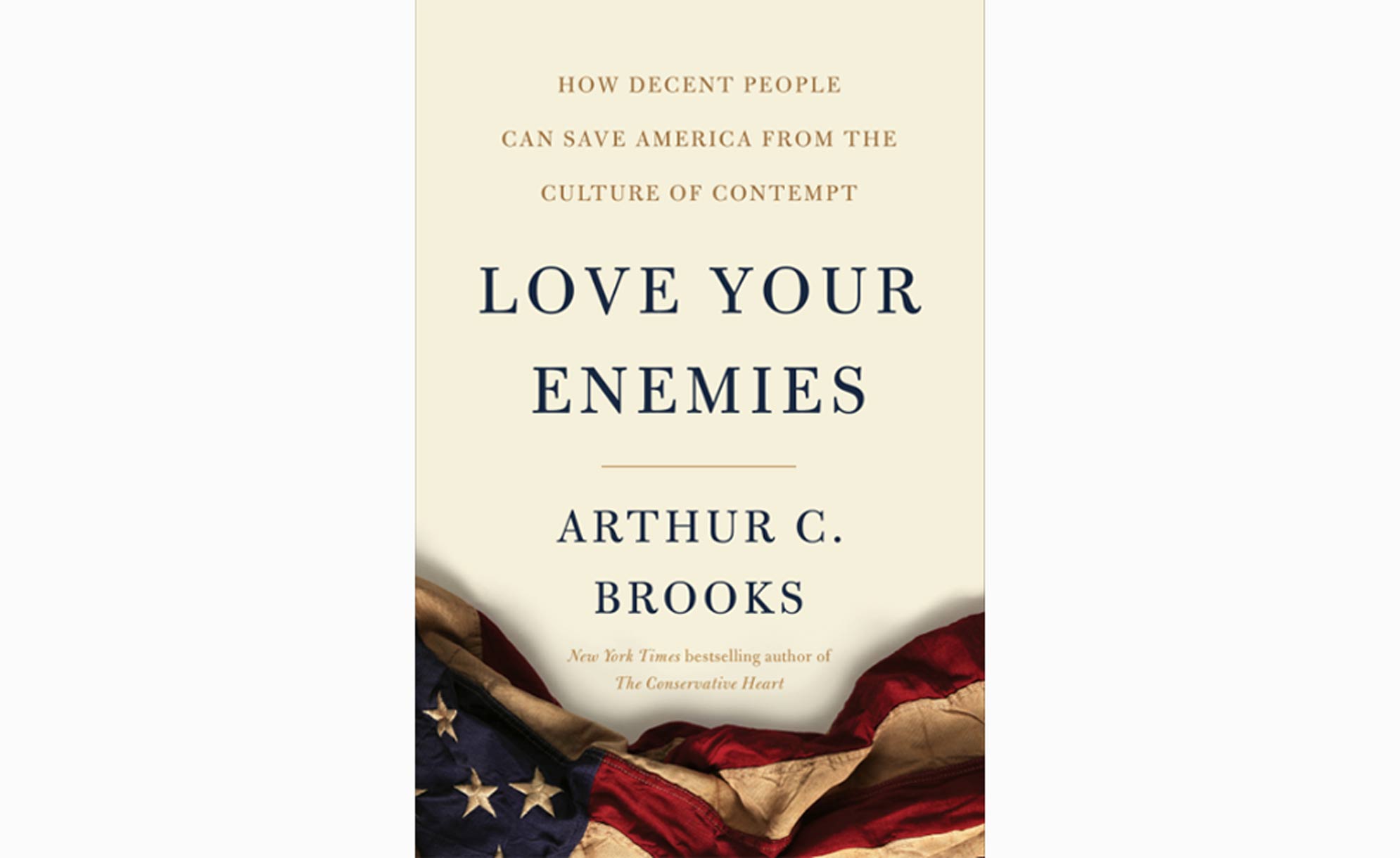

Andrew Leci reviews Arthur Brooks’ Love Your Enemies to discover if decent people save Americans (and the rest of us) from a culture of contempt

Arthur C Brooks is, I suspect, a very nice man. And he’s written a very nice book about some not very nice issues and problems currently faced by the American people – and by implication and association, the rest of the world.

The problem is that the kind of people he needs to be speaking with are not the people who are going to buy his book and read it. A title such as Love Your Enemies is only going to appeal to those who consider this entreaty even possible to fulfil, and they’re probably already doing it to some extent. The exercise in writing the work, therefore – as laudable and as salutary as it is – could be said to amount to little more than ‘preaching to the converted’.

This does not mean that it is not worthwhile, and not important in the pantheon of literature that is geared towards inspiring change, having isolated and illustrated several of the things that are wrong in today’s society. What Brooks focuses on is something that we all know – that the United States of America is anything but united, and antagonistic ideologies are tearing the country apart. We are currently, says the author, in the depths of a ‘cold civil war’.

Brooks relates an incident a few years back when he was driving from New Jersey into New York just prior to Christmas. A devout Roman Catholic, he glimpsed a billboard with what at first seemed like a classic nativity scene – three wise men approaching a stable with “the star shining brightly overhead. A calm, reassuring Christmas image,” he thought. Upon inspection, however, he read: ‘You know it’s a myth. This season, celebrate reason.’ The billboard had been bought and paid for by the American Atheists.

What was Brooks’ response? Indignation? Righteous anger? Blind fury? Not a bit of it. He laughed. And he still does, to this day.

He wasn’t offended. He didn’t take umbrage. He didn’t even contemplate writing to his congressman to complain about immoral (possibly amoral) people ridiculing his faith and calling into question a belief system that he holds dear. He simply found it amusing, and so should we all. Everyone’s entitled to their own opinions in the ‘free world’, and those opinions do not deserve contempt, whether we agree with them or not.

Unfortunately, suggests Brooks, this is exactly what is happening. The political divide, as well as differing cultural and social ideologies have created a polarisation characterised by the two combative sides treating one another with contempt.

Not anger. That wouldn’t be so bad. Anger “seeks to bring someone back into the fold,” according to Brooks. Contempt, on the other hand, “attempts to mock, shame, and permanently exclude from relationships by belittling, humiliating, and ignoring.” The political system in America has created the culture of contempt that Brooks spends much of his time talking about, and it’s fuelled by inadequate leaders and the media – social and mainstream.

Brooks has received criticism with regard to the fact that he doesn’t adequately explain how this situation came about, nor does he provide practical tips as to what can be done. As someone who enjoys interpretation and relishes reading between the lines, I would reject this criticism as both spurious and banal for anyone who doesn’t want to be spoon-fed a belief system or ideology. Some people, believe it or not, would rather look at the facts and draw conclusions of their own, and while Love Your Enemies has many signposts and charted paths, it still makes for an interesting journey if the reader is open. Unfortunately, again, this returns to the point of who might be reading it, and who should be reading it.

The main thrust of Brooks’ book is not that we should all agree – this would make the world a very dull place – and also not that we should all disagree, which would be potentially disastrous. The lesson: let’s disagree better.

This means listening to what others have to say and not being dismissive and contemptuous because their opinions, beliefs and convictions are different to ours. It also involves engaging in an argument without the intention of shooting your opponent down in flames, and affording the necessary respect that proves that while you may disagree with a viewpoint, it has as much right to be held and stated as your own. And guess what? You might even learn something in the process.

Winning an argument by humiliating another and being contemptuous of their views will never produce a good outcome. Try to remember when you last ‘triumphed’ in an argument. Did it feel good to make others feel bad? Do you think you actually changed their minds and that they have now taken your side?

The answer to both questions is almost certainly, no. In fact, your opponent’s opinions will have become more entrenched and will now be accompanied by resentment of you – the person who has treated them (and their views) with contempt. This is not healthy, and the kind of thing, Brooks suggests, that Americans have become addicted to in the political arena.

All of this extends to personal relationships and also leadership, where the competition of ideas has helped to create a world that while far from perfect, is better than it was for most people, and still has enormous potential. Without such competition – disagreements, differences of opinion and divergent strategies on the best way of getting things done – as a species, we wouldn’t have made the progress we have.

Brooks maintains that the qualities of compassion and fairness are innate – aspects of human emotions that would come to the fore were we not taken off in a different direction. Civility and tolerance? All well and good, and not bad things, but simply not good enough; “pitifully low” standards, according to the author. We all need to do more, and just in case reading through a couple of hundred pages of a decent treatise on how to change the world for the better is too onerous a task, his five-rule conclusion chapter on subverting the culture of contempt is bite-sized and as approachable as the man himself, I would imagine. He speaks in public as engagingly as he writes.

Love Your Enemies is packed with wisdom, self-deprecation, lame jokes, and stories, because stories humanise, and make contempt more difficult to sustain. Brooks also has a fair bit to say about leadership, stressing the point that most of us “find it stressful to be bossed”, while the people who are not uncomfortable in the role of a boss are probably tyrants (otherwise known as coercive leaders).

They wield their power by bullying and belittling others, disrespecting their opinions and generally being disdainful. America, Brooks suggests, has too many of these types of ‘leaders’ in the political arena, and this has led to a “ghastly holy war of ideology”. Love Your Enemies is very US-centric – just look at the book’s subtitle – but the themes are universal, and the contempt is everywhere to be seen. The culture of right and wrong, winners and losers, the righteous and the damned is pervasive through the world and is seriously detrimental to progress and wellbeing.

Love Your Enemies is beautifully written. It is clear, to the point, with few linguistic gymnastics, and is infused with the self-conscious tone of a genuine but self-aware geek (fun fact: the man used to be a professional French horn player). But the sentiments are beautiful and, ironically, not even remotely sentimental. The book retains an apolitical stance throughout, which is refreshing, especially bearing in mind that Brooks is the president of a conservative think tank. He recognises and encourages us to understand that we need to focus on change before it’s too late, and for our own sakes.

We need to be surrounding ourselves not with people who agree with us and what we stand for, but those who disagree with us and whose views we need to take on board and understand if genuine progress is to be made and the febrile atmosphere of contempt is to be dissipated.

It is easy to love your family and friends who already love you. Loving your enemies on the other hand is a challenge that simply has to be met.