The old House of Castellane

The House of Castellane, which dates back to the ninth century, is descended from the Counts of Provence.

The family tree reads like a who’s who of nobility and glitterati alike. From Victoire’s great-great-uncle Boniface (Boni) de Castellane, a notable dandy and husband of American railroad heiress Anna Gould, to her uncle Gilles Dufour, well known for his work for Karl Lagerfeld at Fendi and Chanel. And not to mention her paternal grandmother Sylvia Rodriguez de Rivas, Countess de Castilleja de Guzman, later to be known as Sylvia Hennessy with her marriage into the Hennessy family.

Her uncle and grandmother were perhaps particularly influential when it came to her career path. The latter was the one who first got the designer interested in jewellery.

“[My grandmother] was a close friend of Barbara Hutton, the American millionaire married to Cary Grant, who wore emerald tiaras and lived in a palace in Tangiers. She lived in a totally eccentric world with a mix of writers, Hollywood stars and fashion designers – including Christian Dior. This was the real jet set,” she says.

“She wasn’t a grandmother in the classic sense of the term. She was a bit like a Hollywood heroine. She would change [her jewels] up to three times a day [to match her outfits].”

A habit of destroying jewellery

The young de Castellane also had an unfortunate – or in hindsight, fortunate – habit of destroying her own jewellery.

“At the age of five, I dismantled a pair of earrings that my mother had offered me, because I liked them better like that,” she remembers. “At 12, I had my religious medals, which were on a charm bracelet made ‘with love’ by my mother, smelted down so that I could make my own ring.”

This early ability to see creative potential in everyday objects is certainly one of the key drivers of the success de Castellane now enjoys. The Gem Dior is testament to the unique ways in which she views jewellery.

“I’ve done a lot of figurative [designs] in my previous collections. This time, I wanted to zoom inside the jewels and find and show the ‘pixels’ on the stones,” she says.

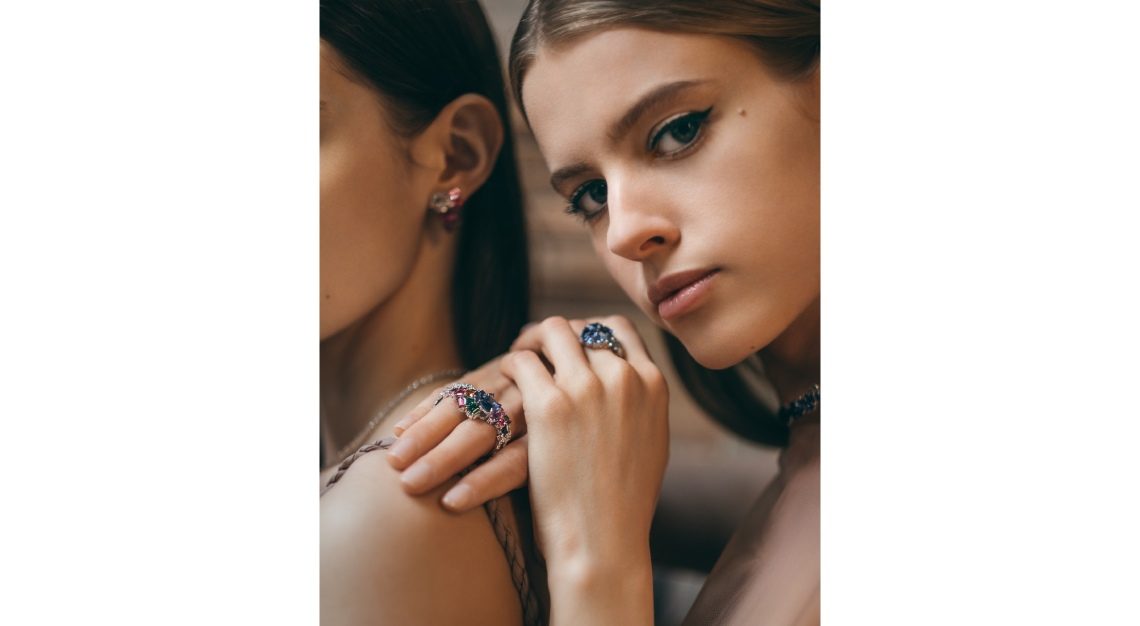

What could be a puzzling statement to the uninitiated is immediately clear when one sees the Gem Dior collection. The 99 jewellery pieces – comprising necklaces, earrings, rings and secret watches – are uniquely architectural, appearing almost pixelated in design.

The idea is to almost make light of conventional jewellery craftsmanship where gems are painstakingly shaped into floral, animal-inspired or classical shapes, and stones are merely used to add colour to an exquisite design.

Instead, de Castellane makes the gems themselves the unavoidable focus of each of the jewellery pieces, grouping them together in crystal-like formations that showcase the colour gradation of natural stones.

In addition to diamonds, emeralds, sapphires and rubies, the designer also plays with the full spectrum of colour offered by precious stones, including spinels, tanzanites, Paraiba tourmalines, rubellites and garnets.

Clustered the way they are, the lights play off each of the stone’s many facets, and the effect, in short, is dazzling. This is exactly the way de Castellane wants it.

“In the beginning it was a man’s world, but women are the ones buying jewellery now and they know exactly what they want,” she says. “They are true collectors but they are also very happy to wear their jewellery and not just keep them [at home]. Jewellery should be worn, loved and admired.”

She adds that she is particularly appreciative of her Chinese female clientele, given their approach to jewellery.

“I particularly love the way Chinese women love jewellery, and I’m very touched by their love for my work,” she says. “Chinese women love stones, and that is something I understand because it’s exactly what I love – the jewels.”

During her teenage years, Victoire de Castellane would go to Parisian nightclubs with her uncle Gilles Dufour, where she would push the sartorial envelope with her sometimes eccentric fashion choices.

Between her uncle’s influence and her mother’s urging, it’s no surprise she ended up working with Karl Lagerfeld.

“My mother sent me to Chanel when I was in high school… I’d worked for the brand since I was 14 years old and it was a fantastic learning experience,” she says. “[Karl] was a good teacher.”

De Castellane formally joined the brand at the age of 22 as a studio assistant, soon after which Lagerfeld appointed her to oversee costume jewellery development. After 14 years of jewellery designing and being Lagerfeld’s muse, LVMH CEO Bernard Arnault launched Dior Joaillerie, of which de Castellane was to become Dior’s fine jewellery creator.