VitroLabs wants to change the source of leather, and not change leather itself – hence, lab-grown leather

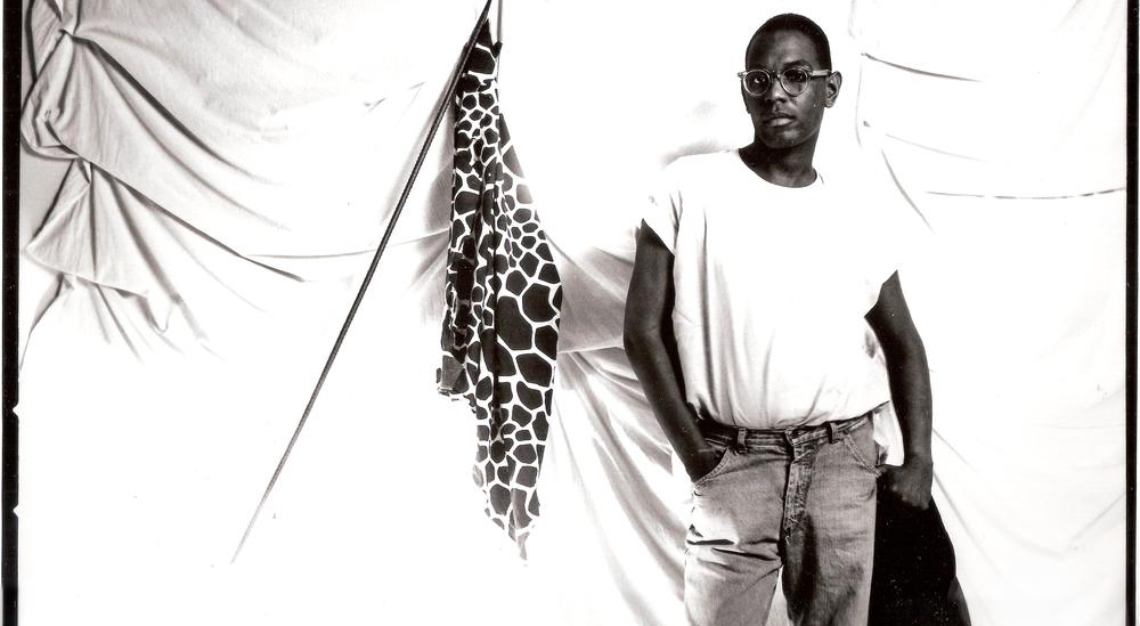

Blame Blade Runner. The Icelandic fashion designer Ingvar Helgason is a self-confessed nerd who says he’s seen the sci-fi classic countless times. It came to mind several years ago, when he was approached by fur companies offering him free pelts with which to design – a typical trade-off for cash-poor fashion types. He declined, ethically conflicted about production methods, but the exchange sparked a question. “In that movie they grow snakes and owls. Wouldn’t it be cool to grow fur in the lab?” he recalls, “What about creating materials we know and love, but doing it in a better way?” He put that idea aside while still designing, but after shuttering his namesake label, he finally pursued the idea in 2015, establishing his startup, the Bay Area-based VitroLabs. Its mission, as he explains it, is simple: “We’re changing the source of leather, not changing leather itself.”

Ethical and sustainable sourcing has been increasingly emphasised in fashion, whether regulating cashmere production or outlawing the use of certain endangered corals in jewellery. Recently, though, several start-ups have emerged to offer low-impact, man-made alternatives to traditional fibres – see Pinãtex, for example, which upcycles the offcut leaves of the pineapple farming industry into a leather substitute. More intriguing, though, are the companies like Helgason’s VitroLabs – they aim not to displace skins but rather replicate them, free of ethical and environmental quandaries. “For me, and a lot of other people who work in the industry, authenticity is key – and I find leather really beautiful, and versatile,” he says, “It’s been used for thousands of years. How can we get the same materials in a better way?”

Ingvar Helgason scouted a professor from London who was working on growing human skin for drug and cosmetic testing, and asked him to expand his expertise into animal skins. They co-founded the company together, creating what they’ve dubbed “cultivated leather.” “We’re using the methods of regenerative medicine but, of course, the inputs are different – we’re using bovine cells,” he says. It echoes much of the leather now in use, which is cow hide; however, this is often produced as a by-product of the meat industry so quality can vary as a result. VitroLabs, of course, can guarantee consistency. Furthermore, though young cows often form the source of the best hides for luxury goods, Europeans are no longer eating veal in the numbers they once did. Consumption per year, according to Helgason, has dropped around 1 percent. At the same time, of course, demand for luxury leather goods has soared, creating a supply-demand imbalance that his start-up is well-positioned to resolve.

He’s also keen to explore the exotics market: crocodile, perhaps, or ostrich, at least once his scientific team better understands how to grow cells other than mammalian in the lab. There’s also a major appeal to cultivating, rather than farming, crocodile: Larger crocs, vital for oversized bags or coats, are so spat-prone that they often bite each other, leaving marks and blemishes that render the skins useless. Lab-grown croc skin won’t risk that same issue.

So far, the company is venture-funded, but Helgason says that a major luxury brand will soon be announced as its first brand partner, with the potential to take a financial stake; VitroLabs products should launch by the end of next year, he promises. The entrepreneur is also mulling expanding beyond leather into other exotics, notably fur. “A lot of brands have stopped working with it, so it’s a shrinking market, but if we can present beautiful pelts that have the same quality and feel, but done in an ethical way? There could be a resurgence of that.”

But isn’t there a broader ethical question to answer? Instead of replicating unsustainable, sometimes unethical, luxury fibres, whether croc skin or mink, shouldn’t we encourage people to embrace new high-tech, high-touch textiles? Helgason is pragmatic in response, likening his product to an electric car or an Impossible burger. “It’s much harder to get people to change their consumption patterns, rather than changing the source of those products – it’s an uphill battle, for sure. So why not give consumers what they’re looking for, but in a better way, with a product that looks and performs the same, with all the beautiful characteristics?” Technology might seem to tarnish luxury’s reputation for handmade precision, but he counters that, too. “If you look at luxury, it was founded on innovation,” he says, citing the redesigned steam trunks from Louis Vuitton with flat tops that allowed stacking or Chanel’s long-chain 55 bag that could be slung crossbody rather than constantly clutched in your hands. He’s hoping VitroLabs’ croc skin will be added to that list very soon.

This story was first published on Robb Report USA