Six-time summiteer and tour operator Mike Hamill has a different approach to the dangerous yet fulfilling experience, ranging from excellent food to swaddling comfort.

My first morning at Everest Base Camp, I awaken to the soft rumbling of a distant avalanche and the faint, nutty aroma of freshly ground coffee. My brain, groggy from slumber and lack of oxygen, doesn’t know whether to be alarmed or excited. The sound of tumbling ice fades, but the smell of a strong French roast only grows stronger.

A rap at my tent door is followed by a cheerful voice saying subha prabhat, or good morning, in Nepalese. I remain in bed, cocooned in the warmth of my electric blanket as the door unzips to reveal an apple-cheeked man holding a tray with a French press and a mug. “Delivery from your barista guy,” he says with a chuckle. He places the much-needed caffeine on a side table, gives a little bow, and exits, zipping me back into my personal mountain sanctuary.

I feel guilty as I take my first sip, recalling how Manhattan socialite-cum-mountaineer Sandy Hill was demonised for her discerning coffee preferences in Into Thin Air, Jon Krakauer’s bestseller that chronicled the 1996 Everest disaster, when a blizzard killed eight summiteers as they attempted their descent. I was among her detractors. Yet here I am having exceptional coffee delivered to my heated geodesic-dome tent with its 4 metres ceiling, queen-size bed, Persian rugs, lighting, and charging outlets. There’s even a humidifier.

These are not comforts I expected to find at the inhospitable foot of the world’s highest peak. In fact, these are luxuries that, before my trek, I questioned even belonged in such a fragile ecosystem—especially for people who claimed to be austere adventurers. Given the option, would Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary have booked massages at base camp after becoming the first humans to step foot on Everest’s 8,849 metres crown? I doubt it.

Their celebrated ascent in 1953 spawned an Everest obsession that, despite multiple tragedies, shows no signs of abating. The numbers are not yet official, but it appears that the Nepalese government issued a historic number of permits in 2023: 463 for 47 teams. It has been a year of record summits but also 17 dead, matching the high set in 2014. I consider myself intrepid, but spending two months and upwards of US$100,000 to trek through a place called the death zone for bragging rights never appealed to me.

Yet I was fascinated to learn what fuels people’s infatuation. And I got my chance in April, when Mike Hamill, the American founder of Climbing the Seven Summits (CTSS), invited me to preview his expedition company’s new Everest Base Camp Rugged Luxury Executive Trek, a rare opportunity to comfortably experience life at the famed staging ground without committing to the time, training, and risk that are inherent in a summit attempt. The trip allowed me to hike with aspirational summiteers while staying in top lodges and spending two nights at base camp. Hints of luxury have made their way to this remote corner of Nepal in recent seasons, but CTSS’s camp is the apex, with next-level amenities including a spa and the unusual ability to host mere trekkers like me.

It’s barely dawn, and a buzz of nerves and anticipation fuels the air of the Hyatt Regency Kathmandu lobby, where 15 CTSS clients from around the globe are tossing their North Face and Patagonia packs onto a pile. Some are hopeful Everest summiteers. Others are attempting Lobuche, Pokalde, and Island Peak, a trio considered Everest boot camp. And then there are those like me, whose planned 64 kilometres hike feels almost embarrassing in comparison.

Hamill, along with his team of Western and Nepali guides, spent the previous day fielding questions and assessing gear. A renowned alpinist who has conquered the Seven Summits six times, he was widely considered the private guide to book for Everest while working for International Mountain Guides for 15 years. He went out on his own in 2017, and despite the curveball of Covid, his company has quickly earned a following in part for its philosophy of marginal gains.

Rooted in competitive cycling, the theory posits that capitalising on every little advantage—a hot shower, chef-prepared meals—results in better physical and mental health and, therefore, a higher success rate. It resonates with my trekking mate Michael Kirby, a 44-year-old Canadian who has been intrigued by Everest since he was a kid and has consumed every film, podcast, book, and YouTube video on mountaineering. He’s here to climb 3 Peaks and saw the Rugged Luxury package as an invaluable opportunity to get firsthand advice from summiteers and spend time at base camp ahead of his 2025 Everest attempt.

While researching outfitters, Kirby found that CTSS stood out with its multitude of options to enhance your comfort level. “Why would you stay at the Holiday Inn if you could upgrade to the Four Seasons?” he reasons on our bus ride to the airport that first morning.

There, we split off into groups. Kirby, two other trekkers, and I make up the Rugged Luxury group and are assigned to Big Tendi Sherpa. Known as the godfather of certified Nepali mountain guides, he has trained an entire generation and has four Everest summits on his résumé. His trekking company, TAG Nepal, is also CTSS’s ground partner, essentially making him Hamill’s right-hand man.

Upon seeing our cherry-red helicopter emblazoned with a fire-spewing dragon, we christen ourselves Team Red Dragon. As we rise above Kathmandu, the city smog clears to reveal terraced rice fields cloaked in mist, snow-dusted pines clinging to ridgelines, and bursts of rhododendron, Nepal’s national flower. The appreciative murmurs are stunned into silence when a sea of clouds parts to reveal the region’s awe-inducing peaks. When Big Tendi points out Everest, Kirby nearly tears up.

It took Norgay and Hillary’s group over two months just to reach base camp. Our 45-minute flight to Lukla saves us over 225 kilometres of trekking, making it possible to complete the journey in 10 days. Set at an elevation of 2,846 metres, this grubby little village is the gateway to the Khumbu, or the Everest region, and its main cobbled thoroughfare is lined with cafés, teahouses, and stalls hawking knockoff Helly Hansen duffels, sleeping bags, and other last-minute outdoor essentials.

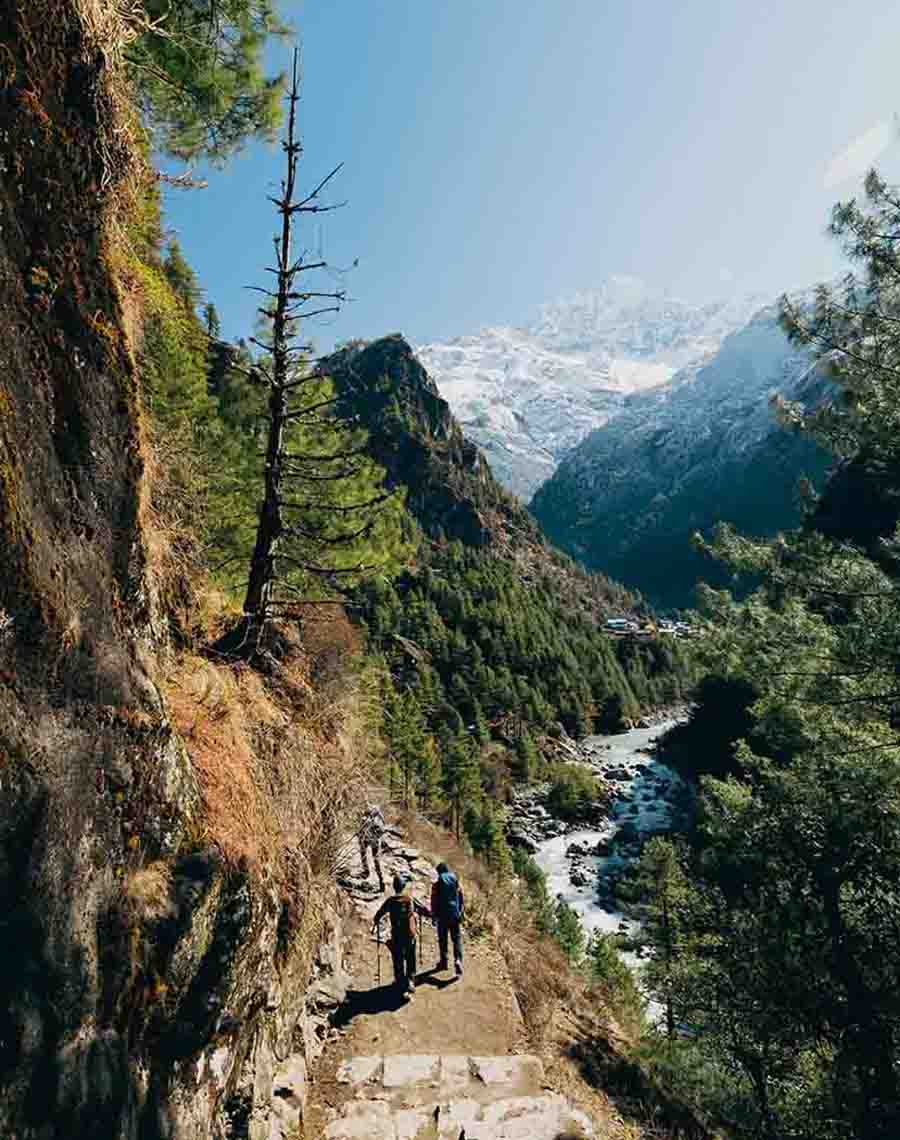

Our group of five sets off under a canopy of Crayola-hued prayer flags, cautiously navigating the street congested with yak and dzo (a yak-cattle hybrid). I marvel at the porters who carry loads rivalling what’s on the backs of these beasts, but in wicker baskets supported only by a strap looped over their foreheads. As we exit town, Big Tendi spins a heavy prayer wheel clockwise, quietly uttering om mani padme hum, an ancient Buddhist mantra for compassion. We all follow his lead, hoping it will bring us luck as we embark on our mellow, five-mile hike along the lush banks of the Dudh Kosi River to Phakding.

“Bistari, bistari,” Big Tendi scolds as I speed ahead on the pine-shaded trail. The Nepalese phrase for “slowly, slowly” becomes my personal mantra. If you do well at altitude and have a strong fitness level, the trek to Everest Base Camp is more active meditation than arduous physical effort. In many ways, it feels like the epitome of slow travel, the antidote to our fast-paced lifestyles.

“We spend two to seven hours a day hiking at a snaillike speed that allows us to acclimate to the altitude but also take in the ever-changing landscapes—thick coniferous forests in the lower Khumbu and moonlike glacial moraines above the tree line—and appreciate the local culture and hospitality.”

Unlike Bhutan, which woos discriminating trekkers with lodge circuits from five-star brands including Aman, Como, and Six Senses, Nepal has always been a backpacker’s paradise known for US$3-a-night rooms in barebones teahouses that charge extra for basic amenities such as showers (often communal) and Wi-Fi. Yeti Mountain Home, our accommodation in the village of Phakding, is a harbinger of change.

Recently remodelled by Mountain Lodges of Nepal, a year-old, family-owned collection of hotels in the Everest and Annapurna regions, this 18-room stone-and-timber inn surprises with its pampering touches. Staff greet us with steamy towels and rum punch; we politely decline the latter but greedily feast on welcome snacks: yak-cheese sticks (the Nepalese spin on mozzarella sticks) and pesto-chicken, onion, and pepper skewers. Nearly all of the vegetables come from the lodge’s organic gardens.

After hot showers in our en suite bathrooms, we regroup around a large fireplace in the dining room. The staff swaddle us in blankets before seating us for dinner. I’d resigned myself to living off dal bhat—lentils and rice—but instead we’re served a multicourse feast of pea soup with homemade bread, garden salad, roast chicken with rice, vegetables, and chocolate profiteroles.

After a solid night’s sleep, we tackle our first real climb en route to Namche Bazaar, a 10.9 kilometres span with 830 metres of elevation gain. “Nepali flat,” jokes Big Tendi. The trail winds through a rhododendron forest bursting with pink, red, and white blooms and repeatedly crosses the glacier-fed Dudh Kosi via suspension bridges draped in tattered prayer flags. As we enter Sagarmatha National Park, a sign warns that jealousy and anger are forbidden here.

A sea of vibrant green and blue roofs signals we’ve made it to Namche, the bustling Sherpa capital, and we climb yet higher past a giant gold-topped stupa and colourful prayer wheels to reach another newly renovated Mountain Lodges of Nepal property, our base for the next two nights.

Even though it’s early April, a thick blanket of clouds has rolled in, and snow flurries start to fall. I’m grateful for a scalding-hot shower and take advantage of the laundry service, Wi-Fi, and an on-call massage therapist who revives my weary legs. Once again, we’re wrapped in blankets at the dinner table, and local staff present us with a veggie hot pot and momos (Tibetan dumplings).

Namche will be the last village where we can purchase any gear, and my fellow trekkers venture out for last-minute supplies such as water-bottle insulators, glacier glasses, and UV nose guards while I read in the fire-warmed living room and watch a veil of mist unfurl around the surrounding valley. Life seems refreshingly stripped down to a simple routine: Walk, eat, relax, sleep, repeat.

Our next few days follow the same rhythm, with leisurely stops for ginger-lemon-honey tea and a visit to the Tengboche Monastery, where Big Tendi has arranged for a puja to protect us on our journey into the mountains. We remove our shoes and step into a room covered with murals of wrathful blue-faced demons painted by renowned Tibetan artist Kappa Kalden in the 1930s and re-created by him after a fire destroyed the originals in 1989. A young monk dressed in a burgundy robe murmurs his blessings against the flicker of butter lamps, and I feel slightly dismayed when he finishes and immediately takes out his phone—apparently a universal addiction.

Perhaps the mountain deities do have sway over our fate, but I largely attribute our safety thus far to Big Tendi. Reaching Everest Base Camp rested and healthy is half the battle, according to Matt Brennan, a 62-year-old American CTSS client on his fourth summit attempt. Big Tendi’s years of wisdom have ensured we don’t overstrain and get altitude sickness, don’t pet the cute dogs (most have rabies and fleas), and avoid crowded sections of trail and teahouses with questionable food.

On day six, we reach Pheriche, a remote farming village nestled in a stark valley sculpted by the Khumbu glacier, and I realise how lucky we’ve been. The Khumbu cough, an infamous high-altitude hack, echoes along the trails, and we hear stories of debilitating gastro disasters. We’ve entered the high alpine, where the severe, rocky landscape feels like outer space.

Mornings get colder as we ascend, and the bleakness of the landscape starts to mess with my head. There are no more smiling children calling out “namaste” on the trails or birdsong in the air. To reach Lobuche, our final base before Everest, we pass a sobering memorial site for fallen climbers, and I wonder if the CTSS summit hopefuls are doubting their quest. “You achieved your dream,” reads one plaque, but I wonder: Shouldn’t the goal be to survive Everest, not just to summit it?

Tucked below the main Lobuche East Peak in an alpine meadow at 4,877 metres, Lobuche Base Camp appears like a mirage of bright yellow tents and a giant white igloo dome. I’m assigned a box tent with a covered porch, a pleasant cot, and carpeted floors.

This is mountaineering territory, and for the first time I feel out of my comfort zone. The climbers use the next days to practise skills and trek to 5,410 metres to acclimatize at Lobuche High Camp; some, including Kirby, will ascend Lobuche Peak. Of the trekkers, I’m the only one up for the challenge of visiting high camp. The terrain is technical and icy, requiring ropes and crampons. The air is noticeably thinner, and for once, I don’t need to be told to slow down. After nearly two and a half hours of climbing and scrambling, we reach our destination. The tents are blanketed in snow, and I feel a huge relief knowing I won’t be sleeping there.

While the summiteers stay behind to overnight at high camp, my Rugged Luxury crew continues on. Our final push to Everest Base Camp is a major effort. Big Tendi would rather we hike on and sleep in clean, comfortable conditions than risk getting sick staying in the grimy yak-herding town of Gorakshep, so we put in a nearly seven-hour day, covering over eight miles. (CTSS is mulling erecting a tented camp en route to break up the long journey.) Traffic jams of ornery yaks and deliriously tired hikers force us to adopt a stop-start pace. By the time we reach the entrance to base camp, Team Red Dragon’s energy is fading. Nearly 95 percent of trekkers would be turning around now, but CTSS is one of the few companies permitted to take non-summiteers into camp proper.

Hamill has selected the farthest site, right below the infamous Khumbu Icefall, to avoid any human waste that might run downhill from other camps (CTSS carries out its waste and garbage). This means another mile-long slog and a full tour of this pop-up village of dreams. The glowing blue ice hypnotises me into a steady pace, and the sight of CTSS’s Big House, an 79 square metres solar-powered geodesic dome that serves as the heart of camp, boosts my spirits. When we officially arrive, I wonder if Hamill also placed his outpost so far back to prevent accommodation envy.

The Big House has views of Everest’s West Shoulder and icefall and is outfitted with neon beanbag chairs, faux greenery, a library, a Ping-Pong table, a yoga area, and an Italian La Cimbali espresso machine manned by my morning “barista guy,” who runs one of Kathmandu’s best cafés. A restaurant-worthy kitchen has been constructed in one tent, and the chefs prepare everything from pork chops to apple pie to fish and chips.

Another dome serves as the world’s highest-altitude day spa, available for massages; other recovery therapies are under discussion, but CTSS ditched plans for an infrared sauna for fear of dehydration. Like a true resort, the camp offers guests a range of lodging options, from standard tents with queen-size beds to residence tents inspired by the first-class apartments-in-the-sky on Etihad Airways. CTSS’s top-of-the-line alpine accommodations have canopied king-size beds, shoe racks, drawers, streaming TVs, and en suite bathrooms with hot showers. After seeing the residences, Kirby tells me he’s considering bringing his wife and daughter for his summit attempt—an Everest family vacation.

My journey has almost ended, but the summiteers’ adventure has just begun. This will be their home away from home for over 30 days. Hamill spent years sleeping in cold, wet tents and eating bland food. He knows all too well that those conditions take a mental and physical toll on performance. “With any other sporting pursuit, you try to save your energy and be comfortable, well-fed, and well-rested to perform,” Hamill rationalises. “For some reason, in climbing, especially on Everest, you are expected to suffer a lot and somehow still be successful.”

CTSS is an attempt to change the narrative. I experience firsthand how the harshness of this landscape can become demoralising. Most mornings it’s below zero; then the midday sun reflects off the ice, scorching us. The ground constantly moves and cracks around you, and avalanches are the norm. Though usually small and not in base camp, they’re unsettling enough to cause a perpetual undercurrent of danger that keeps your nerves on edge. The summiteers will spend at least 11 days acclimatizing above camp, where they must forego showers and share tents to maintain body warmth.

“Base camp is a really big carrot,” Schuyler Evans tells me after returning home from a successful summit. The 44-year-old Brit, who works in energy and finance in Houston, shares famed English climber George Mallory’s motivation for attempting Everest: “Because it is there.” He describes the ascent as the hardest thing he has ever put both his body and mind through, but notes that “practical-fancy” touches at camp made a difference. “You feel primitive,” he says, “but these little nuggets of home, like a tablecloth or fake flowers at the dinner table, bring some humanity to the experience.”

CTSS is not the first company to gussy up its accommodations. The early British expeditions had thousands of porters carrying tables, chairs, the finest Irish whisky, and the best food available from India and back home. In the early 2000s, British expedition leader Russell Brice’s camp reportedly had a “pleasure dome” with a tiger-skin rug, a cappuccino maker, and lounge chairs. Today, other companies, including Elite Expeditions and Madison Mountaineering, have hot showers, Wi-Fi, and hangout tents, but CTSS has raised the bar.

Purists, chief among them American Alan Arnette, the foremost chronicler of Everest, believe luxury has no business at Everest. “To me, mountaineering is all about the three ‘S’ words—suffering, stinking, and summiting,” he tells me before I head to Nepal.

“After two days at base camp, I’m neither suffering nor stinking, but make no mistake: This isn’t a holiday in St. Moritz. Tasty dinners and relaxing massages can’t erase the risks and extreme weather that shadow such a precarious landscape.”

Our final day, a helicopter whisks us back to Lukla. What took 10 days to accomplish on foot takes all of 15 minutes by air. Another chopper transfers us to the grounds of the Hyatt Kathmandu. In my room, I order a glass of Bordeaux—my first drink of the trip—then sink into my bathtub and feel a sense of relief to be back to civilisation and safety. I’d developed a deep emotional attachment to the summiteers I met, and it hits me that they might not all make it back. (I was later relieved to learn that everyone returned home unharmed. Most summitted; a handful, including Brennan, did not. His sherpa got sick, and Brennan insisted on accompanying him back to Camp 4, the station before the final ascent. He is not planning a fifth attempt.)

When I first arrived in Kathmandu, I felt feeble telling summiteers I was “only” hiking to base camp. Upon return, I realise, there is no shame in purely enjoying the mountains of Nepal rather than feeling compelled to “conquer” them—nor in having a good night’s sleep amid comfortable surroundings, eating well, and even indulging in a massage at day’s end. In my years writing about adventure travel, I have often found myself in heightened states of fight-or-flight mode while heli-skiing spines in Alaska or surfing reef breaks in Indonesia. I’m so focused on surviving that I can’t savour the moment. Nobody would say you have to surf Portugal’s 30 metres wave in Nazaré to experience the country’s beautiful coast. Why does one have to summit Everest to appreciate the peak? A semi-strenuous hike with majestic views, at least for me, felt just as rewarding.

If you go: Climbing the Seven Summits Everest Base Camp Rugged Luxury Executive Trek starts at US$18,995 for 18 days; Qatar Airways flies from New York to Kathmandu via Doha.

This story was first published on Robb Report USA