Deep in the Australian outback, the Argyle mine has produced the world’s most spectacular pink stones. But as the last of them are extracted, what will the future hold for these coveted gems?

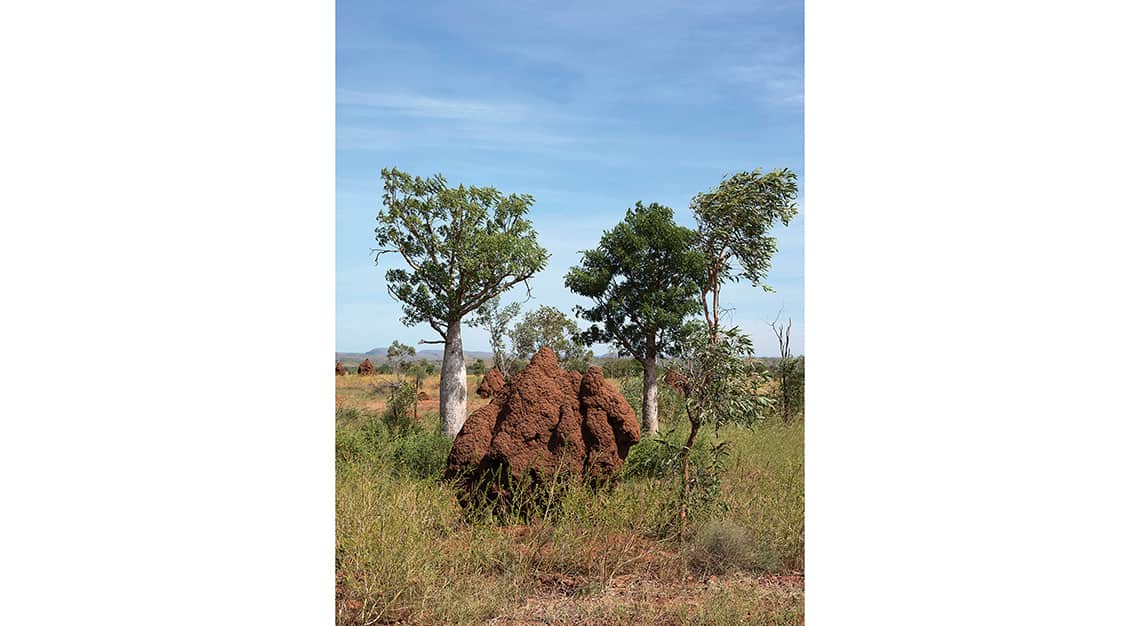

It was the anthills that confirmed their suspicions, glinting inexplicably under the harsh sun of the Australian outback. The geologists had explored the land for a decade, suspecting there might be something precious lurking under the barren, sunbaked earth. Trekking through the outback on foot, they squinted more closely at those sparkling flecks. They were diamonds, shards that the insects had inadvertently ferried to the surface from a deposit, or pipe, below.

What even that team of seasoned diamond hunters couldn’t have guessed then was the size of the seam they’d identified, a few kilometres south of Lake Argyle. When formal operations began in 1983, four years after the initial find, the diamonds from this single mine virtually doubled world production overnight. Named in the lake’s honour, the Argyle mine has produced 865 million carats of rough in the four decades since. Where the shimmering anthills once stood as the only sign of life, there is now a vast gash in the red-brown earth, with steep, stepped walls carved by the mine.

But there was an even greater prize hidden in the teeming shoals of stones, one that the ants hadn’t telegraphed: pink diamonds. Most mines will be lucky to unearth one pink in the entire haul; at Argyle, it’s about one pink carat for every 1,000 carats mined. Even more astonishingly, they are consistently of the highest calibre, with a strong, pure, intense shade.

“To call an Argyle pink rare is an understatement,” says Murray Rayner, a geologist who has worked at Rio Tinto, the mine’s owner, for 16 years. “It’s so much rarer than rare – it shouldn’t exist.”

Indeed, the likelihood of even one such diamond forming was thought akin to winning the lottery twice on the same day; to the delight of Rayner and the other geologists at Argyle, it has happened over and over again. The discovery of pink diamonds here has been vital for the global supply, producing 90 per cent of those sold since it opened; even then, the average annual output has been about 10,000 polished carats.

Until the Argyle seam was found, pink diamonds were so rare that they barely registered on jewellers’ radar. As dealer Scott West explains, what use was it creating a market without some consistent supply? His family firm, LJ West, has long been a major player in coloured diamonds, including Argyle pinks. This mine transformed the market by providing a small but steady stream of top-tier gems – at least until now. Rio Tinto has announced it will shutter operations at Argyle permanently by the end of 2020 – and it estimates that there are just 150 or so Argyle pinks left to be unearthed there before it does. It’s a Herculean task: in the cool, damp tunnels under the earth where the final excavations are taking place, dumpers deposit tons of stony soil, which clatters noisily as it’s sifted, every hour, every day. Those 150 pinks lurk somewhere in that grey sludge, golden ticket-style.

Rio Tinto has aggressively nurtured the Argyle diamond brand since it first understood the value of the pinks hidden here. It launched a formal certification and marketing programme in the ’80s, aiming to connect the name with the best of these stones. One key component of this programme: the annual invitation-only tender each autumn, attended by just 150 of the world’s most prestigious dealers, jewellers and other connoisseurs. Since 1984, they have been invited to fly across the world to tussle over the previous year’s supply of premium pinks, an annual offering that has averaged just 50 carats. (The remainder are sold through Argyle’s distribution network throughout the year.) Each year, that batch would be sold at tender with a theatrical flourish – and at great expense, as when Laurence Graff snapped up every stone in the first tender, creating from them a tremblant flower later purchased by the sultan of Brunei. Per Rio Tinto’s own figures, there’s been double-digit growth in prices each year, which means an investment in one of these rocks in 2000 would have outperformed all major equity indexes.

Argyle diamonds’ appeal isn’t just down to their relative abundance but also their quality. Colourless diamonds are graded via the four-C system (carat, colour, cut and clarity), but in 1995, the US-based Gemological Institute of America refined its classification for their coloured counterparts, factoring in elements like hue, saturation and tone. Argyle pinks were consistent standouts – and it’s all thanks to the process by which they were formed. Or at least that’s the geologists’ theory.

This deposit, they believe, was formed at deeper, hotter levels of the Earth’s crust than a typical pipe, which coalesces around 160km below the surface. The Argyle deposit, then, required more time and greater force to push through to the mantle. Undergoing this process intensified the stress on the diamond seedings in just the right way to turn them pink, according to Rayner. Yet even he cannot be sure. Many colours of diamond, such as blue and yellow, are the result of impurities; pink is an exception, developing under duress via shifts that take place inside the stone at an atomic level. Even today, Rayner and his colleagues cannot fully explain the exact process that creates a pink diamond.

But whatever happened at Argyle, it was well-timed. This pipe doesn’t produce the watery, slightly faded shades unearthed in South Africa or elsewhere. Instead, Argyle’s pink diamonds shine with an intense, bubblegum-like vibrance that acts much like a gemmological fingerprint; it’s unique in the world and makes the stones from this mine instantly recognisable to a loupe-wielding expert.

The geological peculiarities of this seam have had other impacts on the stones as well. Argyle pinks are more delicate and difficult to polish, too. Cutters ruefully analogise finessing a clear diamond and a pink to working on butter versus knots of wood. The twisted subatomic structure that confers the vivid colour is also impossible to replicate in the lab using the standard process, which builds diamonds in layers, slowly, around a seed. (Just in case, Rio Tinto supplies each authentic Argyle with a certificate of origin and, on stones down to 0.08 carats, a laser-inscribed ID number, visible only under magnification.)

The aesthetic appeal and quality of Argyle pinks has helped the value of coloured diamonds as a whole skyrocket in the last 20 years. In the decade to 2017, the median price paid at auction for coloured diamonds rose 122 per cent, according to the Fancy Colour Research Foundation. Argyle pinks, meanwhile, command an additional premium of 10 to 20 per cent over even the finest colours from elsewhere, whether Siberia, South Africa or Tanzania. Panmure Gordon and other banks and analysts predict that throttling the spigot of supply will turbocharge Argyle’s prices.

But the possibility remains that Rio Tinto will sell the well-established Argyle name once the mine is dormant. Industry insiders say the mining giant would likely sell only to a buyer already deeply involved with Argyle, such as a longtime dealer who has stockpiled more than a few pinks and has a vested interest in preserving their prestige – and their price. In that case, one needn’t worry the name will be diluted with Argyle Pink Vodka or Argyle Pink Socks. One potential bidder is Singapore-based John Glajz, who confirms to Robb Report that he has given his non-binding expression of interest. Glajz sees a huge opportunity looming. “Any (Argyle) product out there would become a branded product and would own the word ‘pink’, I guess,” he says. In the intimate world of diamonds, there would be an element of self-policing, too, lessening the likelihood that anyone would dare try to pass off an ersatz pink as an Argyle.

Though several industry players have reportedly put up their paddles, two knowledgeable sources say Rio Tinto has suddenly gone silent about a sale and may be rethinking its strategy. One suggested the holdup could be bidders’ demands that sale data, including confidential client lists, be included in the deal or it could be that the company is simply stalling until after the final, presumably blockbuster tender. A spokeswoman for Rio Tinto declined to comment on the company’s plans, including whether the Argyle name is for sale.

At last year’s tender, with the closure already looming, prices for one-carat vivid pinks were reportedly up about 40 per cent. Though Rio Tinto does not release sales figures, it did announce that several records had been set. This year’s tender was just as exciting, with 64 diamonds, weighing 56.28 carats, plus a secondary assortment of stones bundled into sets and dubbed Everlastings on the block – and the prospect of but one more tender to come. “I can’t think, off the top of my head, of a parallel to that in the jewellery world,” says New York–based Josh Weinman, a dealer who specialises in Argyle. “It’s finite, like a famous artist passing away, where no new art will ever come onto the market.”

Fellow dealer Scott West makes an art analogy as well. “The discovery of Argyle was like when Monet started painting in a profound new way, which other artists then tried to copy, building their style on his,” he says.

And just as the artist’s studio will one day be empty of paintings, so goes the Argyle mine. “It’s bittersweet, just like life – you have to cherish it when it’s here and realise that something beautiful does not necessarily last forever.”