Why it is a painstaking process to create Royal Tokaji’s Essencia

One of the biggest heartbreaks of making wine is a lost vintage, which is usually due to weather conditions before grapes have a chance to fully mature. This has been the case in several years since 2009, the last time—until now—that Royal Tokaji was able to produce bottles of its ultra-rare Essencia. The conditions weren’t right for azsú berries in five out of the six vintages between 2009 and 2016 (the current release), but 2013 offered the biggest heartache of all.

“I think most producers in the region would agree that 2013 is one of the greatest vintages in Tokaji, ever. We had perfect conditions for azsú, and we had amazing quantity as well,” Royal Tokaji managing director Charlie Mount tells Robb Report. “We had a lot of Essencia dripping, but after five or six years in our cellar, we couldn’t find anything that we thought was worth bottling. And it was one of the most painful decisions we’ve ever had, having a huge amount of Essencia not meeting our standards and having to decide not to release the 2013.”

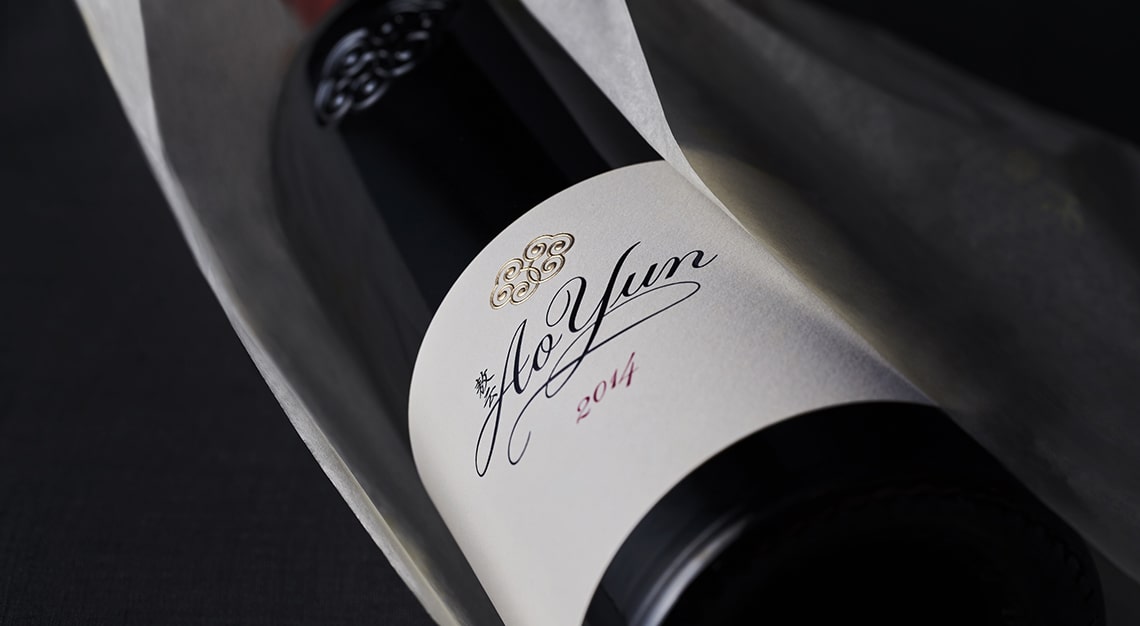

Although neither 2014 nor 2015 provided ideal conditions for enough quality azsú berries to produce Essencia, the summer and fall of 2016 offered perfect circumstances to capture the precious free-run juice (more on that later) that goes into making this prized elixir. And prized it should be. Only the eighth vintage of Essencia released in the winery’s 34-year history, sipping Royal Tokaji 2016 Essencia from specially designed crystal spoons that reveals its deep amber hue and aromas of dried apricot, ripe summer peach, and honeycomb. It rolls over the tongue like syrup with nimble viscosity and a sumptuous vein of acidity that keeps its inherent sweetness from overpowering its flavors of apricot nectar, peach pie, candied orange peel, and fresh honey that leaves a trail of tangerine zest in their wake.

Meaning “dry” in Hungarian, azsú berries are grapes that have been afflicted with Botrytis cinerea, the grey mold called Noble Rot that is responsible for the creation of Tokaji Azsú as well as Sauternes and Spätlese and Beerenauslese Riesling. Unlike common household molds, Botrytis requires an optimal setting to do its work; if it is present in a season that is relentlessly wet, it will ruin the grapes it’s growing on, making them useless for winemaking. But a period of humidity, especially one with cool, foggy mornings, that precedes a dry period just before harvest creates an ideal situation. The fungus dehydrates the grapes, which increases the proportion of fruit sugars and acids, offering a sweeter, more intensely flavoured berry from which to make wine. Affected grapes shrivel to the point that they look like raisins.

In regular azsú wines, botrytised grapes are collected in large baskets known as puttony and added to 136-liter barrels of base wine. The number of baskets of sweet grapes added to the base wine give the Tokaji Aszu the Puttonyos rating of either five or six Puttonyos. For a Tokaji Aszu wine to be labeled today as five Puttonyos, it must have at least 120 grams per litre of residual sugar and a wine labeled as six Puttonyos must have at least 150 grams per litre of residual sugar. Essencia’s sugars can run between 450 and 600 grams, requiring strong acidity to balance out the sugars; Royal Tokaji’s 2016 weighs in at 534.6 g/l of sugar.

Although Tokaji Azsú has been a favorite of noblemen, poets, and artists for centuries, Tokaji Essencia is in a league of its own. While Louis XIV may have proclaimed that Tokaji is “The King of wines, the wine of Kings,” Hugh Johnson OBE, the esteemed British wine writer who founded Royal Tokaji in 1990, has been known to call its Essencia “medieval Viagra.” Each 375-millilitre bottle of Essencia contains the juice of 40 kilograms of dehydrated berries, which comes out to about 50,000 grapes; compare that to an average 750 ml bottle of dry wine, which is made with about 1.1 kg or approximately 200 grapes. The painstaking production process involves picking the finest botrytised grapes from the best plots and then, as Mount says, “It’s a question of waiting.” The term “low-intervention winemaking” is tossed about with abandon in the wine world, but Essencia is truly the epitome of the style.

After harvesting, shriveled Furmint, Harslevelu, and Muscat Blanc grapes that have lost 80 per cent of their water are placed on racks and left to drip. “We don’t press them or apply any pressure so a tiny amount of liquid drips through a grating at the bottom of the collecting vat. We draw it off from time to time, we keep every grape variety and every site separate, and we do an initial selection,” Mount says. The juice absorbs atmospheric liquid from the high humidity wine cellar; naturally occurring yeast from the cellar settles on the surface and a top-down spontaneous fermentation takes place. Up to 70 per cent of that free-run juice is poured into appropriately sized glass demi-johns; as grapes from vineyard plots are kept separate, the containers vary in size from 10 to 50 liters. The entire process takes at least five to seven years; Mount continues, “All along we’re waiting and tasting and towards the end we’ll make a final selection of the batches to be blended and bottled as Essencia.”

Although a bottle of wine boxed with a crystal spoon can seem like a bit of a gimmick, the viscosity makes sipping from a spoon rather than a glass a much more efficient means of imbibing with minimal loss. After all, 15 per cent of the initial juice has already been lost sticking to the grates, and up to 30 per cent more is discarded prior to blending. Only 2,300 bottles of this treasured liquid were made (priced at $1,416 each), and each one holds roughly 25 tablespoon-sized pours; you seriously want to devour every last drop. If you can’t get your hands on a full bottle but are dying to give it a try, a select group of restaurants such as Oiji Mi and Gabriel Kreuther in New York City have bottles and crystal spoons on hand for your sweet sipping pleasure.

This story was first published on Robb Report USA