Art historian and picture researcher, Josine Meijer, examines how the art world is changing its landscape in the coronavirus era, for now, for the future, and possibly forever.

Businesses are closed, people are worried about their work, their homes, their families and friends. They’re concerned about where to get milk, bread, flour, and what’s going to happen to their gym memberships.

And yet the world still turns. Not least the art world.

With art galleries behind locked doors around the world, there is, nevertheless, hope for the art industry, emanating from the galleries themselves, and also from individual artists. There are remarkable efforts in this time of crisis, green-shooting out of despair and hope in equal measure.

Governments are proclaiming the funding they have put in place for art institutions, although whether it will be enough to see them through the COVID-19 closures remains to be seen. In Singapore the government has set aside S$1.6 million in subsidies; in the UK, the Arts Council has pledged £160 million (S$279.5 million), while in the US, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York reported facing a US$100 million (S$139.6 million) loss during closure in the pandemic and will be heavily reliant on its US$3.6 billion (S$5.02 billion) endowment. Smaller, less-renowned galleries in the US and many others in every city around the world, will not have this luxury, and survival is going to be a serious challenge for those outside the nationally funded sector.

Donations from various charities are starting to appear around the world, with the super-wealthy stepping up to the plate in these difficult times, and it could well be that some of the money finds its way into the arts. But it’s quite a difficult ‘sell’ when there is so much hardship in so many other areas.

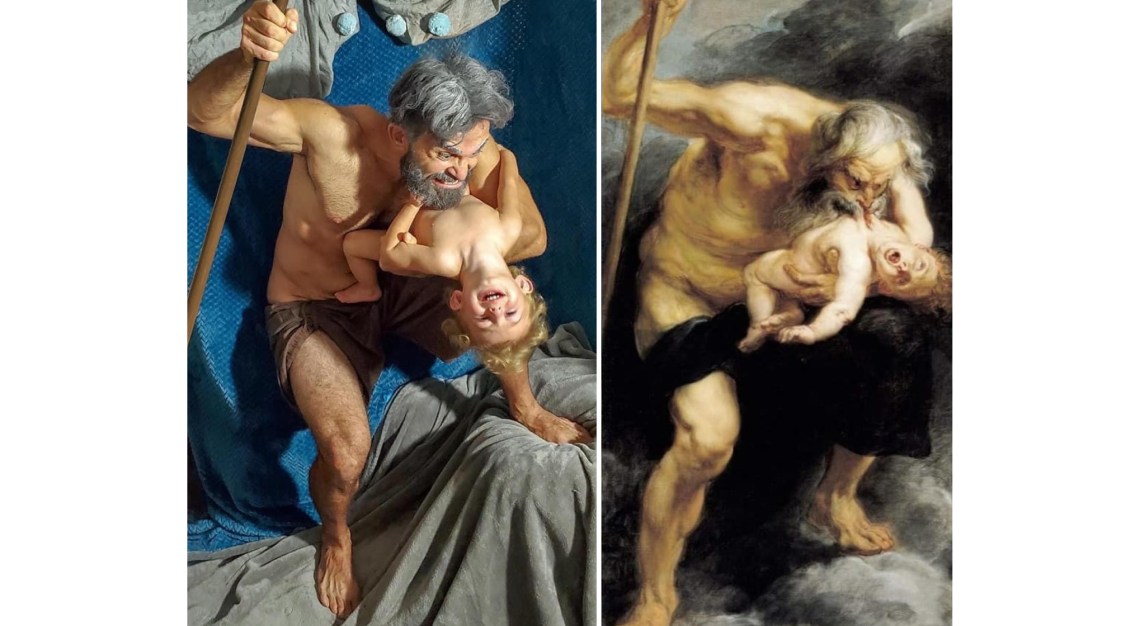

In the meantime, The Getty Museum in Los Angeles, US, responded to the pandemic pretty quickly by asking people to recreate, in their own homes, their favourite paintings, from any gallery around the world, using whatever objects (and people) were to hand. In these days of lockdown, there’s sure to be plenty of things lying about the house – especially people.

The response was a flood of amusing entries, and the possible discovery of a host of talented artists – many of whom didn’t even know that they had talent in the first place.

It’s been a triumph on social media, ticking boxes and conforming to the tropes that make the medium as addictive as it is. In due course, we may well have a new band of artists, able to deal with their own publicity, attracting the attention of galleries and auction houses and, in the fulness of time, refuelling the industry.

Rising artists do not necessarily depend on the large cultural institutions, and some are often not recognised until they are well past their prime, in their dotage, or even after their demise. Desperate times and the desperate measures that tend to accompany them will be forcing the hands of the public (the real patrons) to identify the talents that are to be recognised, and, in turn, the institutions that have been created to house the value of that recognition.

An evolving art force is out there, and if our current institutions fold, new ones will rise up to take their places – possibly with a changed mindset, and more than a passing nod to the greater democratisation of art in general.

The New York Historical Society has recognised the artistic value of what is being produced by those constrained at home and passing the time ‘creating’ – asking for those people to keep their artefacts (for a time) for the world to see them collectively at an unspecified point in the future. Just think of the curatorial potential in preserving the memory of the disastrous, historic time through which we are all living.

We’re already seeing the ‘rainbow of hope’ symbol – painted, knitted, etched, coloured thread woven through railings; on murals, posters, banners, flags – an outpouring when solace is required, and a brighter future sought. We’re seeing photographs of ghostly cities, wildlife re-emerging from the places to which they were relegated, and images of pollution lifting from our most filthy cities that are both a wonder and a salutary lesson.

There will be exhibitions in the future. Possibly many of them. They will surely astound those in their cradles today, along with the generations to come.

What has been remarkable is the surge in innovative responses to this strange new world from both galleries and artists. It is well known that some of the best art is born from the worst of personal / cultural / global times. Caravaggio and Van Gogh, for example, with their psychopathic (for the former in particular, as far as we can ascertain) and psychological illnesses. And there are a plethora of others. Francis Bacon, after the suicide of his lover, George Dyer. Goya in the Napoleonic Wars. Picasso in the Spanish Civil War, to name but a few. Great art can come through great suffering, and certainly through the kind of existential angst that many of us are experiencing at this juncture in history.

For the moment, we are viewing art in a very different way. The larger art galleries have put exhibitions online, while the smaller ones, more often than not, lack the funds to do so, and while experiencing the financial chaos are vulnerable to ‘chancer’ break-ins – such as the recent theft of a Van Gogh painting from the Singer Laren Museum in The Netherlands, which was closed due to the pandemic.

Viewing art online is not the same as up close and personal, but it does keep us in touch with art. It’s hard to imagine a world in which we did not have this technology. It also opens up so much more. Our communication systems are second to none and inspiring not only those who would never have thought of creating a work of art, but also those who are household names.

Not only have individuals, holed up at home, responded independently, they’ve also harkened to the media calls from galleries in accessing and expressing their creative alter egos. Renowned artists have pitched in as well.

Tracey Emin, who famously made her darkly sad romantic life an artistic endeavour on a global scale (My Bed, 1998), has come into the public eye once again with her take on COVID-19. It’s black again. This time, literally. A canvas she is working on is getting blacker and blacker – she is posting the progression over time on Instagram. “In a plague year,” said Emin, “is there any other colour to paint?” She may have a point, but others have taken a different approach.

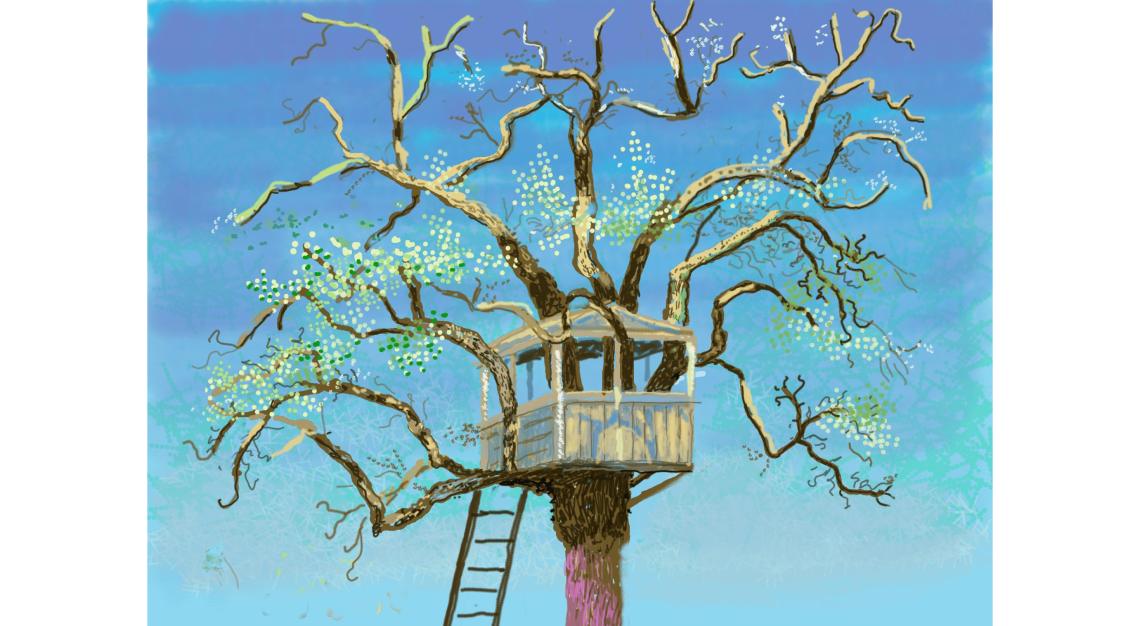

The UK’s national treasure, Sir David Hockney, is on the other end of the spectrum, painting light-filled iPad ‘paintings’ of trees in blossom from his other home in Normandy, France. There are photos of him in the press looking happy in the glorious sunshine.

Patrick Brill (OBE, RA), better known in the art world as ‘Bob and Roberta Smith’, is personally reaching out to the public, with a specific task – like homework – such as painting clouds on a Friday morning.

These are just three different ways of tackling an issue that exists because people can’t visit galleries and need the creative fix of expression during difficult times. They are also prime examples of how new art will be created throughout the world. Art creates patrons, patrons create galleries. In the future, we may well not have the galleries to which we have become used, but there will be others to take their place, whether we like it or not, and they may be very different. The world changes. In so many ways.

History has taught us that even if our longstanding large, prosperous galleries and art institutions cannot weather the storm, the artworks within them will remain. Where they will be housed and how they will be able to be viewed is a matter for conjecture, but they will be there. Perhaps we will embrace the ‘new’ in terms of the way we look at art. On our screens (computer, television, handheld device) – and we’ve already taken great steps towards this with ‘immersive’ exhibitions – Van Gogh’s paintings being among the most recent.

Mankind will always produce art – expression is part of the human condition. Periods in history – epochs, if you prefer – drive the narrative. Our current situation – taking in the entire spectrum from unimaginable suffering to mild inconvenience – will not only shape the art world in the immediate future, but for many years to come. Not only in terms of what is produced, but also in terms of everything that we experience and how we revel in it.