Eddie Hall stayed behind the wheel all 24 hours of France’s iconic contest in 1950, culminating the car’s extensive motorsport provenance

Although Bentley is now known for providing among the poshest driving experiences available, its legacy is built on a storied motorsport foundation. By 1930, the British marque had racked up four consecutive wins at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, forging an indomitable reputation as a sporting brand. When Bentley was acquired by rival Rolls-Royce in 1931, the ensuing identity crisis put Bentley’s inherent edginess in grave danger.

By 1934, Bentley’s repute got so soft that when Edward “Eddie” Ramsden Hall sized up his bid to run the gruelling Mille Miglia, he chose an MG Magnette for the race and picked up a Bentley for the comfort of learning the course on practice runs. As fate would have it, the cushy Flying B—which, in fact, was based on a Rolls-Royce 20/25—ran a trouble-free 6,440 km on the recce, while the MG blew a head gasket in Siena and dropped out of the race.

Hall, a can-do Renaissance man who had bobsledded in the Olympics and set mountaineering records, did the only logical thing a gentleman of means would do: he aimed to campaign his beastly Bentley in the 1936 24 Hours of Le Mans. The ambitious privateer also managed to persuade Rolls to provide a degree of factory support.

France being France, the 1936 edition of the world’s most notorious endurance race ended up being cancelled due to worker strikes. Undeterred, Hall dove into a nearly two-decade-long cycle of racing and modifying his long-nosed Bentley, upgrading its hardware and tweaking the body through wind-tunnel tests so that every ounce of performance was extracted from its hulking chassis. So successful was his personalized racer that, according to an Autocar article, circa 1942, it remained unbeaten in its class and upheld a record for being the “single car driven most continuously by the same individual.”

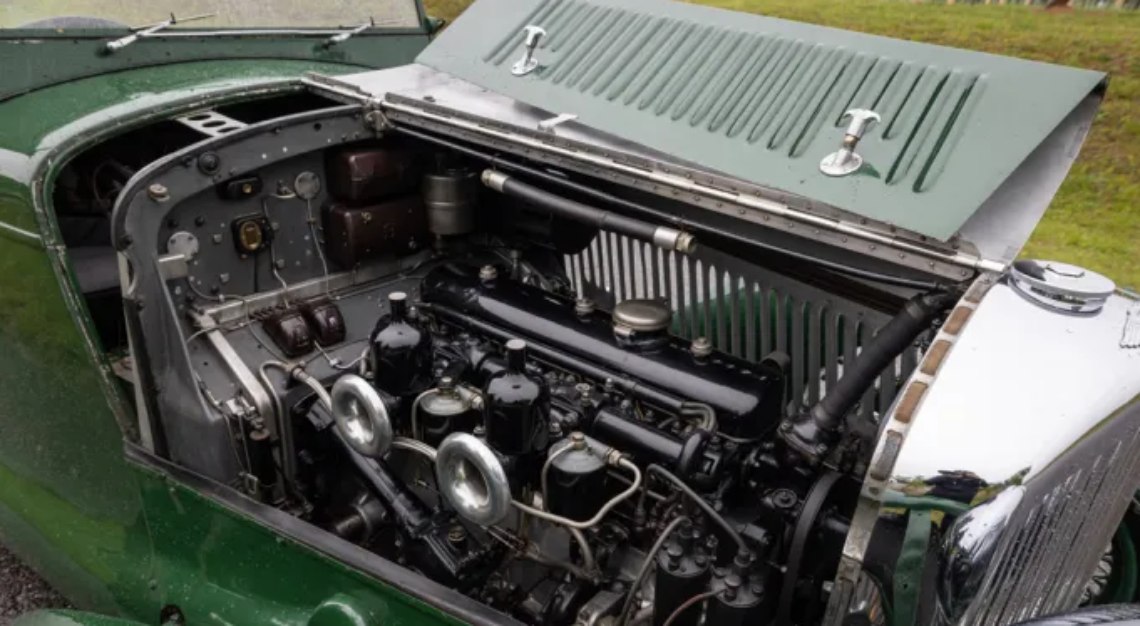

By 1950, the Bentley wore streamlined bodywork and a 4.25-litre inline-six power plant with an impressive 9.1:1 compression ratio. Still hoping to compete in the iconic French endurance contest, and seeking a momentous way to celebrate his 50th birthday, Hall entered the 17-year-old Bentley at Le Mans, assigning racer Tom Clarke as a co-driver. Though Clarke was a seasoned competitor, Hall entered the history books by doing the unthinkable: staying put in the driver’s seat and piloting the entirety of the 24-hour race. Hall finished a remarkable eighth overall, averaging 133 km/hr amidst a field of far more contemporary models that also enjoyed the luxury of multiple drivers. And while there is usually doubt about such seemingly superhuman feats, Hall’s solo drive has gone essentially unchallenged, suggesting that he did indeed complete the entire 24-hour contest himself.

Le Mans was this Bentley’s last race, as Hall, following an illustrious career as a gentleman racer, moved to Canada soon after. The car was subsequently acquired by Briggs Cunningham, who had finished 11th at that year’s Le Mans in his striking and streamlined “Le Monstre” Cadillac. The Bentley, along with much of Cunningham’s collection, was eventually passed along to Miles Collier. Interestingly, Collier’s father and uncle also competed in the 1950 edition of Le Mans, campaigning a Cadillac Coupe de Ville for Cunningham and finishing one spot ahead of “Le Monstre.” Hall’s Bentley 4 ¼ Liter is now a part of Miles Collier’s Revs Institute Collection, and I was fortunate enough to receive an invitation to experience this remarkable machine during a recent visit to rural Georgia.

The vast majority of historic race cars require intense mental and physical involvement. This is especially true of prewar examples because they’re often ponderous and blunt, requiring effort and concentration to heave around corners. Often adding to the experience are pedals and controls where they aren’t supposed to be, culminating in an operational process that is anathema to driving enjoyment.

Sliding into the cockpit of Hall’s former Bentley on a rainy morning in the Georgia countryside is daunting enough. This chariot, inked in British Racing Green, sits tall, with a fixed seat tilted forward and a lengthy snout that hides a hulking, hot-rodded power plant from a bygone era. Despite the body’s superhero proportions, the cockpit is cramped and compact. Those red flags are assuaged by an immediate air of familiarity: the right-hand-drive configuration places the gear-shift lever on the right side (where nature intended it), and the pedals are in a traditional clutch/brake/accelerator arrangement. The instrumentation is straightforward and beautiful, displaying clear, white needles and markers against black backgrounds with crimson at critical spots, like the tachometer. The latter demarcates redline at a modest 4,500 rpm.

While it takes some effort to wrench the oversized steering wheel at a walking pace, the throttle fuelling and clutch take-up are remarkably easy and accurate, responding with a sense of surprising crispness. And then there’s acceleration from the torquey, low-revving engine which shoves the two-seater ahead with a confident whisk. A gated shifter (think Ferrari) positions the gear selector into place in no uncertain terms, facilitated by short, precise throws of the lever.

Because years of assiduous work have gone into lightening everything from the bodywork to the seat frame, this Bentley 4 ¼ Liter weighs in at a mere 1374 kg, including 11 kg of fuel. That’s less weight than the modern (and rather diminutive) Lotus Emira. Though the machine moves down the road with surefooted certainty, its lightweighting also helps it feel surprisingly manoeuvrable for a vehicle of its vintage. Bolstering the unexpectedly zesty dynamics is a sense of usability and intuitiveness, making the car a pleasure to drive. Far from a relic of the past, this Bentley feels weirdly contemporary and alive, flourishing its purposeful performance with elegantly tapered fenders and a silhouette that must have looked striking as it dashed across the Le Mans circuit at speed.

The 1933 Bentley 4 ¼ Liter “Eddie Hall” race car exudes a feeling of specialness that goes far beyond its age, its nameplate, and its arresting shape. It stands apart because it carries the personal history of years of passionate ownership which, at its zenith, became defined by 24 near-nonstop hours of heroic, all-out racing.

The halo effect of Le Mans becomes palpable in almost anything and anyone who takes up its gauntlet. The grit required to maintain peak performance for a full day is gruelling enough when split between two or three drivers; to cross the finish without anyone else taking a turn is nothing short of remarkable. For that reason alone, Eddie Hall’s Bentley has an air of singularity that is all but impossible to replicate.

The word “supercar” gets tossed around quite a bit to describe serially built, ultra-high-performance sports cars. In a world of manufactured exceptionalism and commodified luxury, the “Eddie Hall” Bentley bears the rare distinction of deserving every superlative it receives.