On the island of Carriacou, Alwyn Enoe has spent five decades sculpting his acclaimed wooden vessels

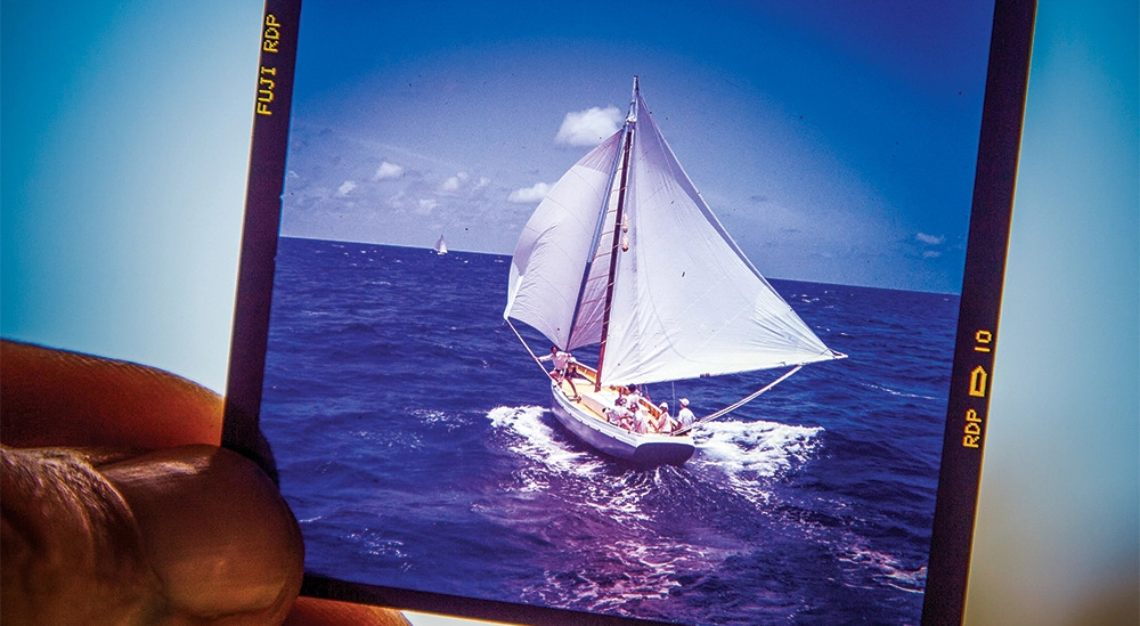

On the island of Carriacou, the largest of the Grenadines, lives a man who has spent five decades keeping a tenuous hold on a boatbuilding tradition that was the lifeblood of the area for centuries. Alwyn Enoe (above) sculpts his wooden vessels with an ancient cutting tool called an adze, knowing that each will be appreciated for not only its simple beauty but also its impressive speed.

Born in 1943, Enoe started his seafaring life aboard island traders until one caught fire. Several of the crew, including his best friend, died that night. Unwilling to return to sailing but residing where water was ever present, Enoe became a shipwright in 1973, honing a skill that was brought to the islands by Scottish immigrants centuries ago. He is now widely thought to be the last artisan of what are known as Carriacou sloops.

Over the years, Enoe has staunchly refused to give up his craft (even while moonlighting at modern shipyards to earn a living). In the process, he has become something of a Grenadian celebrity, thanks in part to his many champion boats, as well as an award-winning 2015 documentary called Vanishing Sail. The film’s director, Alexis Andrews, is a superyacht photographer who purchased an Enoe sloop that had sunk off Antigua, rebuilt it and sailed it to the Grenadines, where he commissioned another vessel, Genesis, from Enoe.

Carriacou sloops were cargo workhorses, and because they sometimes hauled rum or other contraband, they had to be fast to outrun patrol boats. It’s no wonder then that Enoe’s designs still perform well in local races, including the Antigua Classic Yacht Regatta and the West Indies and Carriacou regattas.

Enoe embarks upon each project by crafting a unique half-hull scale model. Then come the cutting and hauling of greenheart for the keel and white cedar for the ribs, and the construction, right on the beach. His favourite step is caulking with cotton twine, just as it’s been done since the beginning. “The caulking means the boat will be safe—protected from the sea,” says Enoe. The sound of the caulking hammer, which could once be heard throughout these islands, signals that the end of fabrication is at hand.

The whole village comes together to launch a boat by tilting it on its side and then pushing and pulling it into the waves. Exodus, the 12.8-metrer subject of Andrews’s film, took form over three years and is now owned by Nicola Cornwell, who has a home on the nearby island of Bequia. “It made sense to get something totally designed for these waters, and it was important to us to contribute to the community by buying a boat that was part of the sailing heritage here,” she says. “She’s perfect for these waters and a joy to sail.”

Andrews also finds Genesis inextricable from the environment and culture that produced it. “She’s in her element, and she’s one of the elements because she’s born of this place,” he says. “She’s the water, the land, the wind and the pride of the local men.”

At age 79, Enoe is hopeful his venerable skills will outlive him. “I think the trade can continue, but we need a school,” he says. “We depend on the sea for a living, and building boats gives our young people a trade, a feeling of their culture and confidence.”

This story was first published on Robb Report USA