Now and Forever

Back To Basics: What’s A Perpetual Calendar?

A perpetual calendar is a watch or clock that takes account of the day, date, month and leap year in addition to the time. Often it also includes phases of the moon. It evolved from timepieces with the astronomical function, which displays celestial information like the sky map, moon phases, sunset/sunrise, equation of time and sidereal time.

It’s often been said that time is the child of astronomy and if that truly is so, then the perpetual calendar has to be the most quintessential representation of the concept of time.

In essence, time is a phenomenon effected by three rotations: that of the earth around itself, the moon around the earth and the earth around the sun. These three cyclical events respectively make up a day, a month and a year, and with them come the four seasons, as well as the equinoxes and solstices.

Which Calendar Does The Complication Mostly Use?

The most widely used calendar is the Gregorian system although religious practitioners continue to refer to other systems like the Jewish and Islamic calendars. Businessmen typically follow the ISO week date calendar.

Comprised of 365 days with 11 months of 30 or 31 days and one with 28 or 29 days, the Gregorian system is the most accurate and ubiquitous calendar. It can be traced back to the Roman calendar which had only 10 months beginning in the spring, and had an unspecified duration for winter. Eventually, the ruling monarchs introduced two more months, which helped stabilise the calendar although it still required constant intercalation.

Curiously, the month of September is the ninth month even though septem is seven in Latin. Similarly, October is the 10th month instead of the eighth, November is the 11th instead of the ninth, and December is the 12th instead of the 10th. This happened when Julius Caeser reformed the Roman calendar in 46BC by implementing the leap year, where February was to be shortened to 28 days but given one additional day every four years. Renamed the Julian calendar, it eradicated the need for an intercalary month.

In honour of that contribution, according to the classicist Matthew Nicholls in an interview with the BBC, the month of July was renamed after Caeser, and August, after his son Augustus.

What About The Leap Year?

As for why February became the month chosen to reflect the leap year, no one really knows. One possible reason is that February was regarded as the least important month since it occurs during the end of winter. Another theory is that March was historically regarded as the first month of the year because it heralded spring, so February being the last month of the year was best suited to house the intercalary day.

The Julian calendar remained in use for centuries until 1582, when Pope Gregory XIII added the final touch. He decreed that every year that is divisible by four is considered a leap year, but years that are divisible by 100, also called centurial years, are only considered leap years if they are also divisible by 400. These in turn are called secular years. The good pope’s objective was to refine the prevailing calendar further such that movable feasts dependent on the equinoxes and solstices, like Easter, may be stabilised to the nearest month.

Perpetual calendars are typically based on the Gregorian calendar unless otherwise stated.

The Most Accurate Perpetual Calendar Is…

Indeed, not all perpetual calendars are created equal. Most can quite ably track the day, date, month and leap year – with a moon phase display thrown in for good measure – but only a few are able to account for the secular years. A perpetual calendar that is also programmed to adjust for the secular years is called a secular perpetual calendar, and it is the most accurate type of calendar complication there is.

It is not clear who invented the perpetual calendar mechanism, but historians estimate that it happened around 1772 to 1773. An English watchmaker, the prolific Thomas Mudge who invented a number of key watchmaking components, is credited as having made the first portable perpetual calendar, although it wasn’t a watch.

Patek Phillipe’s Quest: To Make The Most Accurate Perpetual Calendars

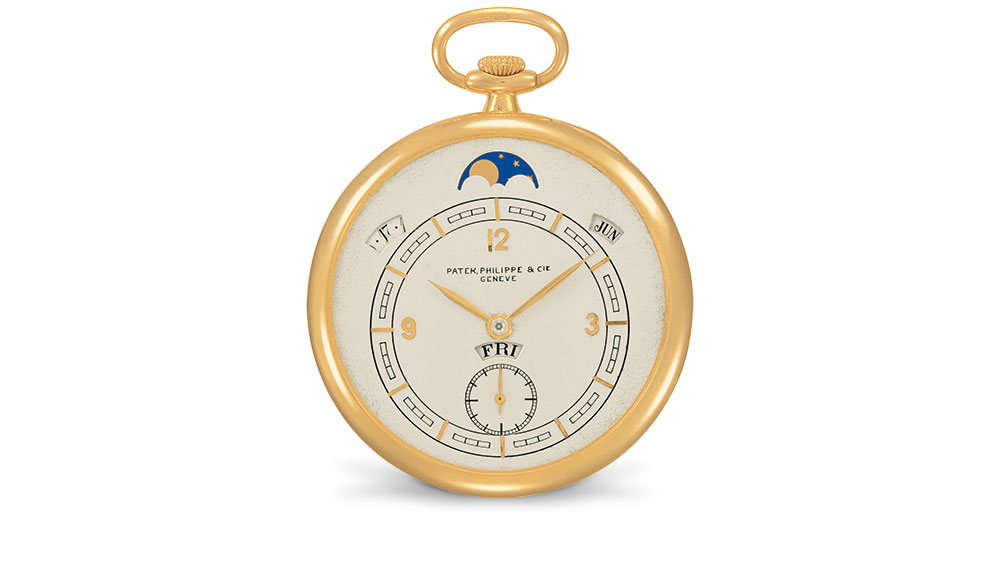

In 1864, Patek Philippe produced a perpetual calendar pocket watch, which was a coverless type with an enamel dial and had Spanish indications. The movement blank came from Nicole & Audemars in Vallee de Joux. It would be several decades later, in 1889, that the company filed a patent for the perpetual calendar mechanism in a timepiece. This movement was able to advance the day, date, month and lunar phases instantaneously and comprises a system of heart-pieces, levers and star wheels.

By the 20th century, Patek Philippe continued to produce perpetual calendars. This was the era of wristwatches and one key challenge faced by manufactures of the time was how to fit movements, which were predominantly pocket watch-sized, into a wristwatch. In 1925, Patek Philippe brilliantly made a perpetual calendar wristwatch using a woman’s pendant watch movement. The first known example of a wristwatch perpetual calendar, this timepiece had been commissioned by Thomas Emery from North America, but today it belongs to the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva.

Since the 1970s, Patek Philippe only produces secular perpetual calendars. The first timepiece with this enhancement is a Lepine-style pocket watch Ref 871. It had a satellite wheel that rotates once every 400 years. The famous Patek Philippe Calibre 89 made on the occasion of the manufacture’s 150th anniversary is also a secular perpetual calendar.

Perpetual Calendars With Leap Years?

While perpetual calendars were able to account for the leap years, they didn’t always display this information. It wasn’t easy at all for watchmakers to include the leap year indication. This feature first appeared only in the 1980s. Patek Philippe’s Ref 3450 was made with the Calibre 27-460QB, which has a red dot leap year indicator.

Some of the earliest modern perpetual calendars by Patek Philippe include Ref 1526 made between 1941 and 1952, powered by Calibre 12-120QP, as well as Ref 2499 with Calibre 27 SC produced between 1951 and 1963, not forgetting the water-resistant perpetual calendars Ref 1591 and Ref 2438. One special piece, Ref 1527, was a unique watch given to Henri Stern by his father, Charles.

Through the years, Patek Philippe continually improved on its perpetual calendars, introducing the first self-winding one in 1962 with Ref 3448. Calibre 27-460Q had a twin in-line display for the day and month, and an analogue date display encircling the moon phases. In 1985, it made an ultrathin perpetual calendar, Ref 3940 with Calibre 240Q, which was only 3.88mm

in height.

Getting Crafty With Various Styles

Other than the twin in-line style, Patek Philippe also produces perpetual calendars in the star shape and the circular arc styles. Current models, like Refs 5327, 5140, 7140, 5139 and 5940, all follow the star-shape format and the circular arc style can be seen in Refs 5159, 5496 and 5160. The 2017 Baselworld highlight, Ref 5320G-001, comes with the classical twin in-line format.

It must be said that perpetual calendars that display the calendar information through windows are significantly more difficult to produce than those that use hands because of the greater weight and inertia of discs versus hands. According to Patek Philippe, it takes 20 milliseconds for the movement to make its instantaneous jumps.

All Patek Philippe perpetual calendar movements either function on a 12-tooth cam coupled with a satellite wheel for February or a 48-tooth cam that makes a full rotation once every four years. Like a mechanical computer, this slow-moving wheel with irregular shaped teeth is marked to accurately reflect the right number of days for every month including February, over a four-year period. A large lever triggers the date wheel, which drives an intermediate wheel.

This intermediate wheel, in turn, moves the month wheel, which moves another intermediate wheel, which advances the 48-tooth cam.

Like this, the perpetual calendar relentlessly keeps track of time’s steadfast passage, following it second after second, minute after minute, hour after hour and so on, until the days bleed into weeks, weeks into months, months into years, and years into centuries.

It is one of Big Three classical complications in traditional haute horlogerie and will continue inspiring watch connoisseurs until the end of time.