The final chapter of the Argyle mine’s 41-year-long story goes into reshaping the land and returning it to Mother Nature

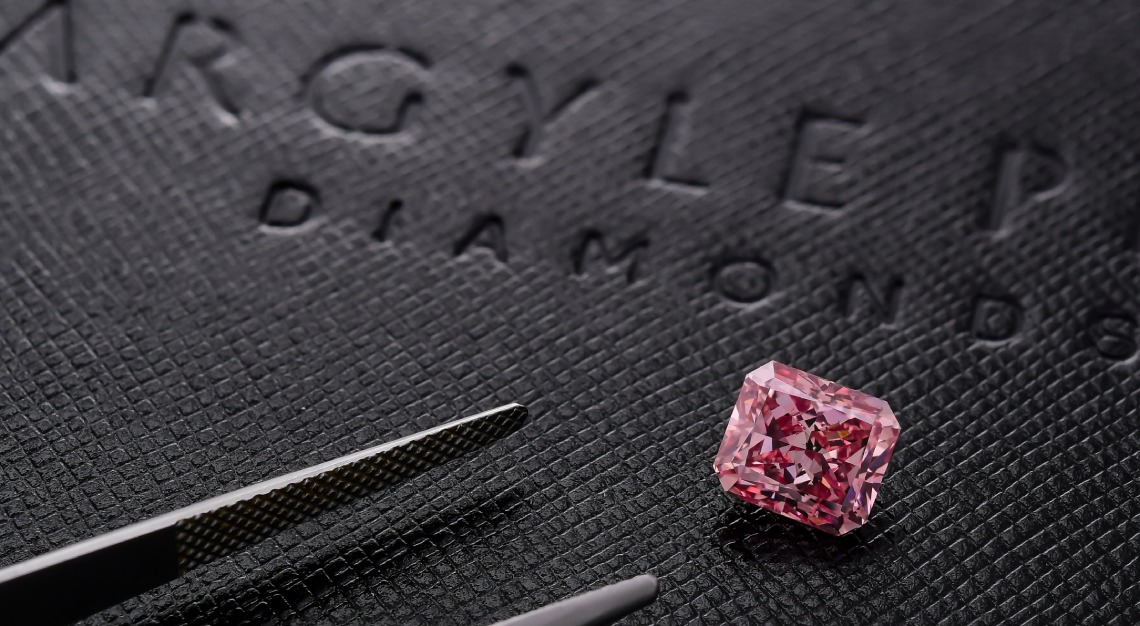

Pink diamonds from the Argyle mine in Western Australia have been likened to works of art like Fabergé eggs. Their story began in 1979 when, after spending more than 10 years exploring an area three times the size of England, geologists unearthed a diamond deposit, which became one of the world’s largest mines.

At its peak in 1994, Argyle contributed approximately 40 per cent of global diamond supply (its lifetime total is approximately 865+ million carats of rough diamonds from the mine’s commencement to closure). While the company broke new ground with innovative marketing campaigns for its Champagne and Cognac-coloured diamonds, what catapulted Argyle to mythic status were its red and pink diamonds, which were considered the rarest and most valuable in the world.

Murray Rayner, Argyle’s principal geologist, explains the geological phenomenon behind these minerals. “Pink diamonds are flukes of nature. In addition to a million to one journey through earth via a volcano that leads to white diamond formation, pink diamonds require specific pressure at a molecular level, which twists the diamond’s lattice structure, transforming their colour from white to pink.”

But Australia is not the only source for pink diamonds as history informs us. So what makes this deposit stand out? Coloured diamond specialist, John Glajz, explains: “Unlike other sources, diamonds from Argyle display a higher degree of colour saturation in their more intense/vivid range, with greater diversity in hues. This is dissimilar to anything we’ve seen before.”

Exemplifying their allure, pricing for Argyle pink diamonds has touched stratospheric heights in recent years. Marie Chiam, sales and marketing manager at Argyle Pink Diamonds, says: “Since 2000, the price of our annual Argyle Pink Tender Diamonds has increased by over 600 per cent.”

The other factor driving demand for Argyle pink diamonds is their mine-to-market traceability with an unbroken chain of custody and certification, reassuring clients that the diamonds are responsibly sourced.

But Argyle’s story is not just about the hero pink and red diamonds. According to the Fancy Colour Research Foundation (FCRF), jewellers and watchmakers have not yet fully grasped the magnitude of the mine’s closure. Argyle is the only consistent source for natural pink diamonds from 0.01 carat (one millimetre) to 0.20 carat (3.8mm), used to cover large surfaces in luxurious watches or high jewellery. Eden Rachminov, chairperson, FCRF, explains: “In the short- to medium-term, we won’t see new jewellery and watch designs with small pink diamonds. Luxury pieces adorned with natural pink diamonds will disappear and grow into an extremely sought-after collectible.”

The last day of mining at Argyle was 3 November 2020. What does the closure mean for local communities that had been economically dependent on the mine for the past four decades? What is the environmental impact? How will Argyle fill the geological and economic void it has left behind? From the start, the Argyle team were sensitive to their environmental footprint. When the time came for the operation to move from the vast open pit to underground, they were the first in the region to implement block cave mining, a technique that cuts beneath the orebody allowing it to ‘cave’ under its weight without blasting, causing less surface stress and delivering a safer mining experience.

Additionally, they entered into a participation agreement with the traditional owners, outlining activities to promote education, training employment and business development opportunities. Argyle also established long-term financial trusts for the traditional owners, indexed to the company’s net profits, and provided additional contributions to each of the five surrounding indigenous communities and the original signatories (or their descendants) of the participation agreement. A portion of this is also utilised annually to fund health, culture, governance and community development activities.

As part of the mine closure plans, Argyle is offering employment in rehabilitation and closure projects, work with other Rio Tinto mines, retraining/reskilling, and retirement options.

According to Argyle, it will take three to five years to dismantle the operational infrastructure, reshape the land, and undertake revegetation activities to re-establish a natural ecosystem. The underground mine cave and the open pit will gradually fill with water and become a permanent pit lake: the only remaining mining evidence at the site.

Chris Richards, general manager, closure readiness, elaborates: “This work will provide significant economic opportunities, benefiting the region, particularly the traditional owner businesses. The last chapters of the Argyle story are yet to be written and we will continue to be an important part of the East Kimberley community for many years to come.”

This story first appeared in the March 2021 issue, which you may purchase as a hard or digital copy. Celebrate Robb Report Singapore’s 100th issue with us here