Paint My Love

As fine as it is rare, traditional hand enamelling is a bona fide treasure in modern watchmaking. For numerous watch aficionados, Suzanne Rohr and Anita Porchet are the two remaining grand high masters of the trade and their enamel creations, recognised as the creme de la creme, are much sought-after.

In November 2017, their immense talent and contributions to luxury watchmaking were officially lauded when the pair was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Geneve the industry’s equivalent of the Oscars.

Rohr, who is notoriously private and media-shy, stepped into the spotlight for the first time in her career which spanned over five decades. In her time, she has trained numerous enamellers and the most prodigious of all is Porchet. She is Rohr’s own protege and one who has indisputably come into her own.

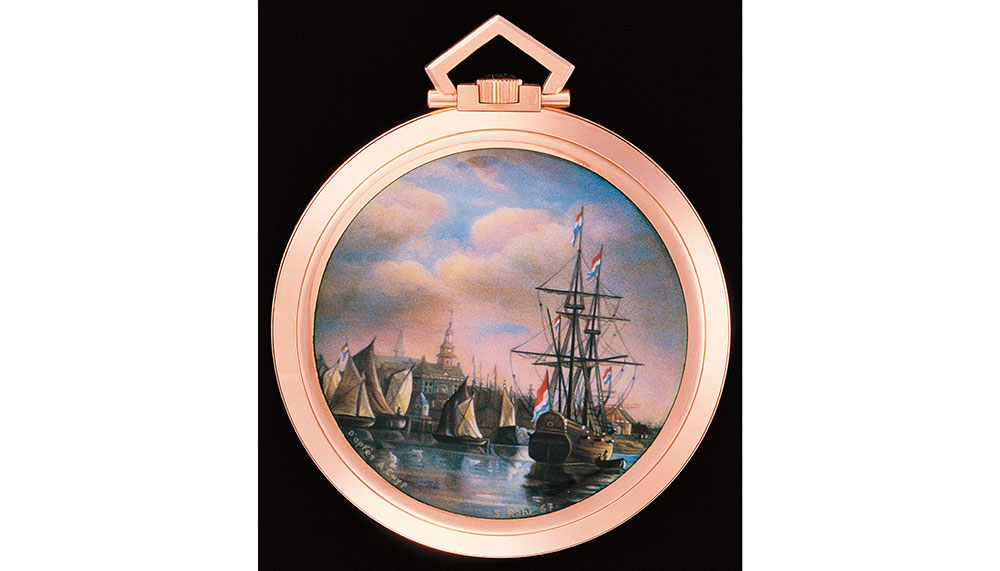

Many of Rohr’s dials take several months, or as long as two years, to complete. To date, she’s made approximately 100 enamels and of these, 26 are lovingly preserved in the Patek Philippe Museum. Some auction houses have, on occasion, had the rare pleasure to come across her work.

An Enamel’s Worth

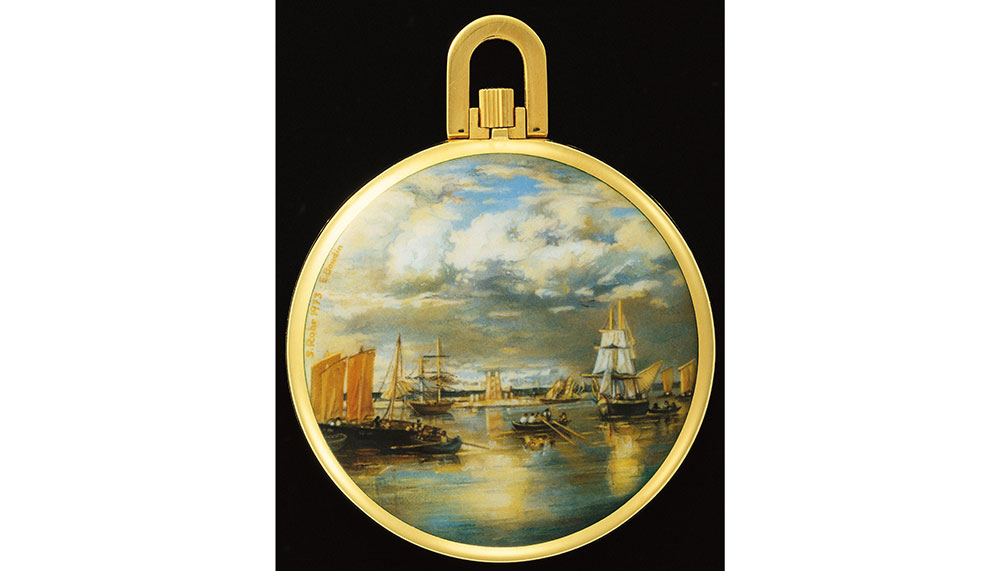

In 2005, Sotheby’s sold a gold open-faced pocket watch that has a caseback decorated with a Gustave Courbet painting depicting Chateau de Chillon, signed by Rohr and dated 1978. The estimate was €15,000 to €20,000 (S$25,000 – S$32,000), but the final price was €50,400 (S$82,000) including buyer’s premium. Rendered with striking detail, it is an outstanding showcase of Rohr’s speciality, the Geneva Technique, which is miniature painting with grand feu enamel.

Now in her 70s, Rohr remains an independent artist although since 2009 she had dedicated all of her time to just one watch company: Patek Philippe. Thierry Stern, president of Patek Philippe, relates in a 2013 interview with WorldTempus that it takes 20 years as an apprentice to even come close to being a grand feu miniature enameller, and that today the art is mastered by Rohr alone.

Sharing The Baton

Yet as age catches up with her, Rohr is slowing down. “A piece that once took her a year now takes two,” says Stern, and this is perhaps where Porchet comes in. Sharing the award with Rohr, Porchet began her career in the 1980s and trained directly under Rohr, so one could say that she learned from none but the very best.

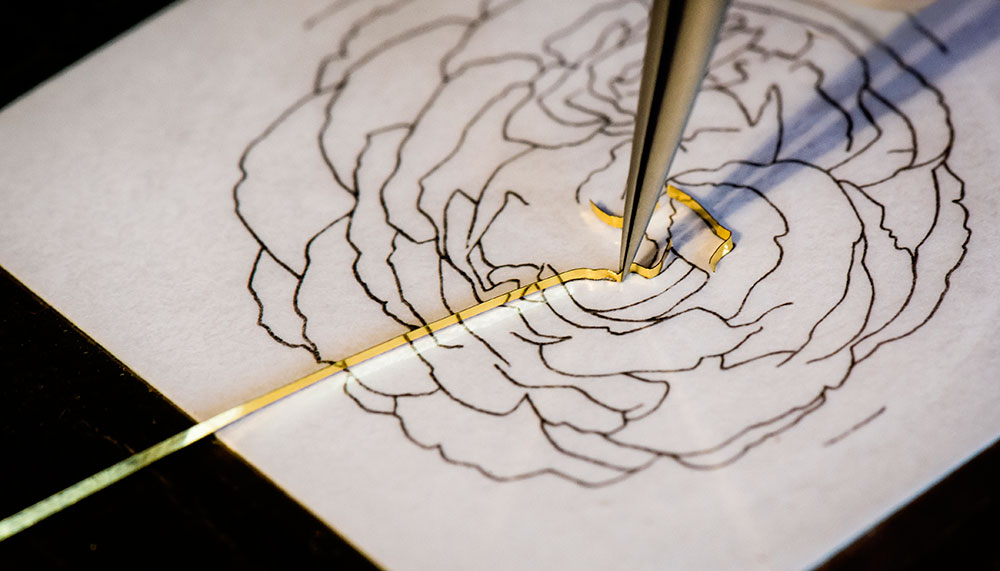

But unlike her teacher, and indeed all her predecessors, Porchet is accomplished in all the different enamelling techniques: cloisonne, champleve, plique-a-jour, grisaille, paillonee and miniature painting.

Porchet works independently; she has her own studio in the canton of Vaud and a small team of apprentices working together as they learn – or learning together as they work. Enamelling, like all art, is a lifelong pursuit. One could become a master of it, but could one ever truly master it? Even Porchet herself hesitates to make such a claim.

Claim To Fame

Some of her best-known works are the earliest paillonee enamel dials for Jaquet Droz. Porchet uses decades-old vintage paillons (gold leaves) which she had painstakingly collected over years, making the timepieces doubly rare. Porchet also works with Patek Philippe, producing its famous dome clocks, and had also produced the beautiful trio in Vacheron Constantin’s Metiers d’Art Florilege collection. Together with her team, she had also made special pieces for Piaget and Hermes.

Porchet’s enamels can be easily identified as they all bear her initials. Obviously enamel dials made by her own hands are priced at a premium to those made by her apprentices. The unique Hermes Arceau Tyger Tyger, for instance, was priced at S$131,600 as compared to the Slim d’Hermes Dans Un Jardin Anglais which was listed at S$84,400 and Slim d’Hermes Promenade De Longchamp at S$91,600.

The Future Of Enamel (Masters)

With the demand for enamel timepieces far outstripping supply, it’s no wonder that the industry’s biggest brands have wasted no time investing in the craft and nurturing it among younger artisans. Many have already established in-house teams or opened institutions dedicated to reviving the traditional metiers d’arts. Yet the gulf between the old masters like Rohr and Porchet and the newcomers will always remain palpable.

For watch collectors, there are real concerns. With a new generation of enamellers in the market, supply will increase and prices may go down but only for the new watches, while enamels made by great masters will become increasingly valuable. Although commendable, by thrusting Rohr and Porchet into the limelight, the guys behind the Geneva Grand Prix just might have accelerated the inevitable.