Patek Philippe’s CHF600 million production facility in the outskirts of Geneva finally opens its doors to select collectors and partners

Patek Philippe calls it PP6, the brand’s sixth production wing at Plan-les-Ouates in the Genevan suburbs; a watchmaking plant that will birth all your Calatravas, Nautiluses, Aquanauts, Gonodolos and Twenty~4s for foreseeable decades to come. A creative hub, inner sanctum and manufacturing monolith rolled into one, PP6 took five years to construct and cost almost CHF600 million—and it is bigger and better than any facility that Patek Philippe has built.

PP6 needed to be massive, too. Especially when the 184-year-old company has outgrown itself several times over. Patek Philippe has come a long way from the 19th century, when its watchmakers made timepieces at the top floor of its historic building on rue du Rhône, along Lake Geneva, which is now an iconic landmark that houses its flagship salon. And also, from the facilities it constructed in 1964 and 1996, which quickly filled to capacity.

Though PP6 officially opened in 2020, it remained a mystery to people outside Patek Philippe, no thanks to a pandemic that shuttered global borders. Almost three years on, however, Robb Report Singapore finally had a chance to tour the facility. It was as much a peek into the inner workings of Patek Philippe as it was a view to the foresight of Thierry Stern, the company’s president, and his father and predecessor, Philip, who in the 1990s had already envisioned a futureproof manufacture that would house Patek Philippe’s production departments and ateliers under one roof.

Opposites attract

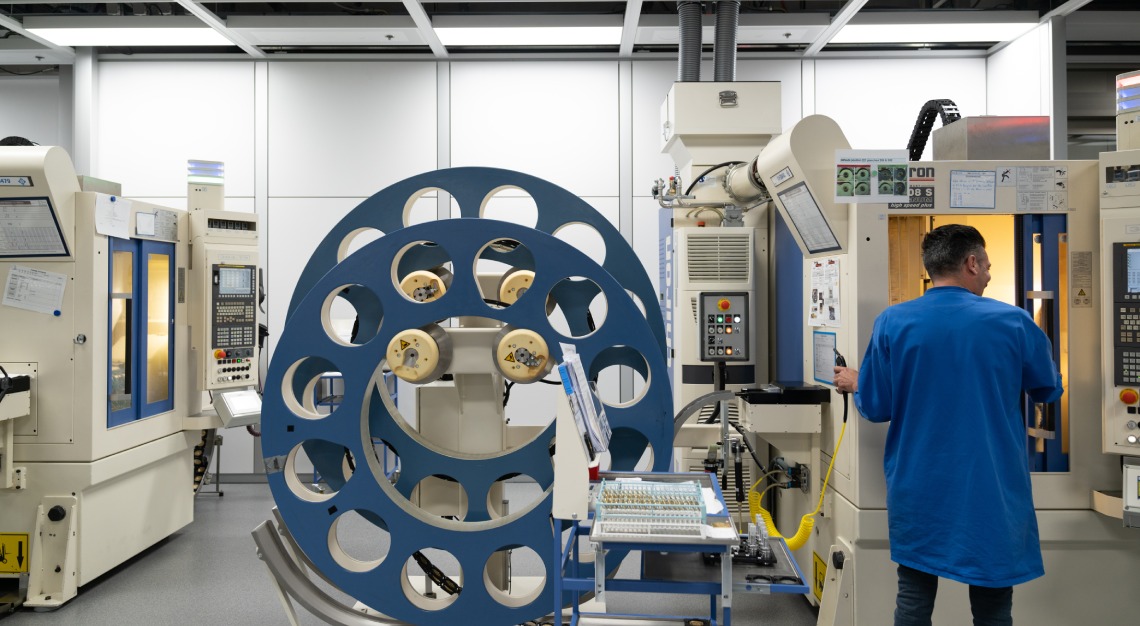

Walking along the wide corridors that seem to stretch forever, one cannot help but be struck by the delicious contradictions that the building and its inhabitants offer. Within the factory is a confluence of man and machine, tradition and innovation, and things big and small.

The building is huge. PP6 comprises 10 floors, including four basement levels, covering over 133,000sqm. This enormous structure is committed to manufacturing tiny components that are machined with micron-level precision.

“Thierry never compromises on the thinness of the watch. At the start of creating every new watch, the early versions are always too thick for him,” says the brand’s head of watch development, Philip Barat, at an earlier interview. And so, as the guide leads me through PP6, documenting the journey of Patek Philippe’s watches from conception to delivery, there is a constant reminder that I am experiencing scale at its extremes.

In a room thick with the smell of oil and lubricant, are gigantic precision-cutting machines that can make any watch part imaginable. The guide puts a component the size of an ant on my palm. I hold my breath, in case I accidentally blow the speck of metal off my hand.

Elsewhere in the building, in spacious rooms that are flooded with natural light, I see watchmakers hunched over their workbenches, assembling components and transforming them into precious and highly coveted works of mechanical art.

Built to last

Patek Philippe says PP6 looks like “a huge ocean liner with clearly defined forms”. On the inside, the building, certainly runs with the organisation and efficiency of a super boat.

The first three floors comprise departments that are responsible for the machining and finishing of movement parts, the assembly of exterior parts and gem-setting, and the restoration team. Up one level, one finds Patek Philippe’s research and development as well as haute horlogerie departments. And yet another floor up, artisans apply rare handcrafting skills such engraving, enamelling and wood micro-marquetry on highly exclusive creations.

It is true that the production process in an establishment such as Patek Philippe is well-defined— almost formulaic, even. Make watch parts. Finish and decorate said parts. Assemble them. Encase and test the watches. Deliver watches to customers. However, like the appreciation of horology itself, it is the details that set the company’s methods apart.

Patek Philippe’s watch production process is rigorous. Yet, it also strives to be inspired and creative. In the rooms where the watch parts are machined, there is clockwork relentlessness: cutting, cleaning, polishing and checking of thousands of components. And doing it over and over again. At a station where bracelets are made, I am told that the distinctive links of a Nautilus bracelet require 55 steps to construct, craft and put together. Towards the end of the tour, an enamellist demonstrates her artisanship and dexterity with the cloisonne enamelling technique, using thin gold wires to form intricate patterns and applying coloured enamel to the crevices—a skill that took her years to master.

Indeed, a visit to PP6 not only offers an insight to the enormity of tasks that motivated Stern to plan for a facility that brings together all the company’s operations since 2009, it is also a glimpse into the scrupulous labour that goes into making every Patek Philippe watch.

When the facility opened three years ago, Patek Philippe was making about 62,000 watches a year. The figure hasn’t changed much. Stern himself has taken care to express—many times in various interviews—that customers should not be expecting more watches to be rolled out. Not even with the opening of PP6. Instead, Patek Philippe’s objective was to ensure that the standard of its watches and resources are upheld “to cope with the expanding challenges of the present and the future”. Longevity and quality, not quantity, lie at the heart of PP6’s mission.